The Cumberland Forest Project: Conservation at Scale

With many years in the making, this innovative project demonstrates the climate benefits of sustainable forest management while providing positive conservation, community and financial returns.

2024 Cumberland Forest Impact Report

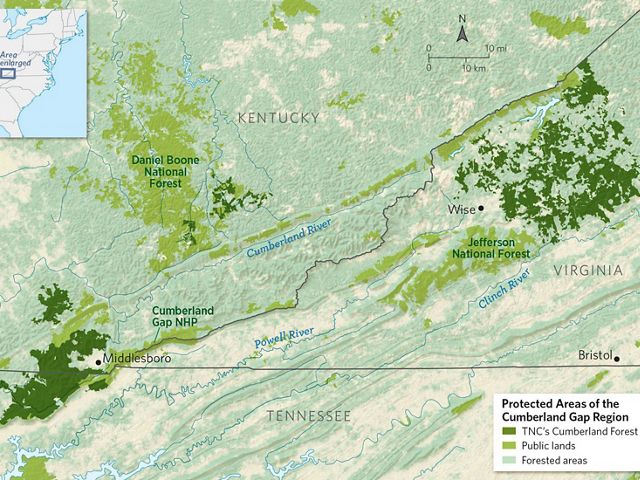

ExploreAt 253,000 acres, the Cumberland Forest Project is one of The Nature Conservancy’s largest-ever conservation efforts in the eastern United States—larger than Shenandoah and Acadia National Parks combined. This vast forest landscape spans two parcels: the Highlands in Southwest Virginia and Ataya along the Kentucky-Tennessee border.

The project was financed using an inventive approach by TNC’s in-house impact investing team, NatureVest, which structured and closed a sustainable forestry fund to purchase and manage the working forest.

The land currently being managed holds cultural and traditional significance for the Cherokee, Shawnee and Yuchi Nations and peoples. These areas are also historical sites of trade, gathering and healing for numerous other Indigenous communities.

In keeping with the land’s rich history, TNC seeks to safeguard this forest and support climate change efforts on two fronts: by storing millions of tons of carbon dioxide and by connecting a migratory corridor that scientists believe could be one of North America’s most important escape routes as plant and animal species shift their ranges to cooler climates.

Explore the Cumberland Forest

Cumberland Forest Project Newsroom

-

- Forbes (April 17, 2024, paywall): Imaginative Grand Conservation Model In The Appalachians Opens The Door To Conservation At Scale

- Renewable Energy Magazine (April 2, 2024): Forum Brings Together Innovators to Develop Energy Solutions for Appalachia

- WYMT (March 19, 2024): 7,000 trees planted on former surface mine site

- Cardinal News (March 19, 2024): Lynchburg to host public meeting on downtown project; more

- WEKU (March 18, 2024): Environmental groups, Beam Suntory organize reforestation effort on former mine site in Hazard

- UVA Wise (March 18, 2024): Cumberland Forest Community Fund Opens 2024 Grant Applications for Local, Nature-Based Projects in Southwest Virginia

- Louisville Public Media (December 26, 2023): A new conservation easement in eastern Kentucky is one of the largest in state history

- Middlesboro News (December 21, 2023, paywall): Nonprofits unite to bring solar to Eastern Kentucky

- Louisiana Illuminator (November 24, 2023): New life for old coal: Minelands and power plants are hot renewable development spots

- Middlesboro News (October 12, 2023, paywall): Conservation groups finalize acquisition of Fern Lake

- WPLN (October 6, 2023): The Cumberland Gap is a natural trail across the Appalachians. One little piece just got protected.

- Cumberland River Compact (September 25, 2023): Reforesting Mine Lands in Appalachia

- UVA Wise (July 17, 2023): UVA Wise and The Nature Conservancy Announce 2023 Cumberland Forest Community Fund Award Recipients

- The New York Times (June 10, 2023): When Chopping Down Trees Is a Gift to the Environment

-

- RTO Insider (October 23, 2022): Solar Farm Trend Turns Old Coal Mines Green

- National Geographic (August 16, 2022, paywall): In a warming climate, we need to radically rethink how we conserve nature

- Power Engineering (July 1, 2022): DOE launches $500 million effort to turn mines into clean energy hubs

- WYMT (April 12, 2022): Conservation partners reforest former EKY mine site

- WTVQ (April 12, 2022): Conservation partners reforest former mine lands in Bell County

- The Washington Post (March 8, 2022): In Virginia, abandoned coal mines are transformed into solar farms

- WPLN News (January 28, 2022): Tennessee to protect songbirds, elk and other wildlife habitat in state’s largest-ever conservation deal

- Energy News Network (September 29, 2021): Meet the Virginia conservationist trying to turn old coalfields into solar farms

- Solar Power World (September 13, 2021): Dominion Energy and The Nature Conservancy plan solar project on former Virginia coalfield

- Yale Insights (June 11, 2021): What Does It Take to Create Financial Products That Can Save the Planet?

- WJHL (June 3, 2021): Former coal mine land to be transformed into solar energy sites in Wise County

-

- Environmental Finance (2020): Impact fund of the year: The Nature Conservancy's sustainable forestry fund

- Down for Change (August 12, 2020): Cutting Carbon by Hugging Trees: The Cumberland Forest Project

- Cleary Gottlieb (June 30, 2020): Cumberland Forest Project Wins Environmental Finance ‘Impact Fund of the Year’ Award

- The Roanoke Star (August 20, 2019): Nature Conservancy Partners With State of VA to Permanently Protect 22,856 Acres in Southwest Virginia

- Virginia Mercury (August 7, 2019): Despite legislative blocks, one form of carbon cap-and-trade is alive and well in Virginia

- REI Co-Op (July 30, 2019): The Nature Conservancy Preserves Nearly 400 Square Miles of Appalachian Forest

Innovative Funding: Investing in Nature

The project is structured as an impact investment fund that seeks competitive rates of return for third-party investors who have an interest in the creation of environmental and social benefits.

By carefully managing the project’s forests and enrolling them in the California Carbon Market and under Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC®) FSC® - C008922 certification, the project aims to improve overall forest health while supporting local forestry jobs and generating revenue to pay back our conservation-minded investors. Attracting private investment capital allows us to implement conservation projects on the ground at a greater scale and at a faster pace.

Quote: Gabby Lynch

We’re managing these properties in a way that creates positive returns through this investment model and creates value for communities that are searching for a future that includes a more diverse and sustainable economy.

TNC is a co-investor in the fund and manages the properties as the fund’s investment manager.

The project is actively working to place conservation and open space easements and covenants on as much of the property as possible. This ensures permanent public access for outdoor recreation and obligates future owners to continue maintaining the land's biodiversity and forest productivity.

TNC’s ardent donors and supporters have made it clear how much nature means to them. With this effort, we’re showing that by describing the economic value of nature, in language that financial markets understand, private capital can be enlisted to do even more to tackle the dual challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss.

Conserving Nature’s Diversity Into the Future

-

The Importance of the Cumberland Forest

The diverse topography of this forest makes it resilient to climate change’s effects. View the Interactive Mapping Experience

A stronghold is a place that is fortified against a threat. For a plant or animal that needs a certain temperature or moisture range to thrive, the threats of climate change are all too real. The forests of the Central Appalachians—including the Cumberland region—are some of the best examples of climate strongholds.

A climate stronghold is a natural place with enough diversity in its elevation and geology that even as the planet warms, species can survive by moving around within its microclimates, migrating over time to avoid unsuitable conditions. In the eastern U.S., those paths are filled with developed areas such as cities; by maintaining migration route options, a large conservation project like Cumberland Forest is giving biodiversity the best possible chance.

Quote: Dr. Mark Anderson

This gives us hope that if we work to keep these special places strong, they will keep nature strong.

Since launching the project in 2018, TNC has used open space easements to secure permanent protection on 47% of the project’s total acreage. This includes successful placement of a public access conservation easement on 55,000 acres of the Ataya property in Kentucky through the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife and 43,000 acres of the Ataya property in Tennessee through the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency—the largest easement of its kind in both Kentucky and Tennessee history—and establishment of a 23,000-acre open space easement in the Clinch River watershed on the Highlands property in Virginia through the Virginia Department of Forestry.

In the sections below, explore highlights from the project, as we continue to make meaningful progress towards long-term impact goals related to sustainable forest management, land and water conservation, climate change mitigation, recreational access, and local economic development.

Cumberland Forest Impact Goals

Jump to Forestry | Climate Mitigation | Coal to Solar | Restoring Mined Lands | Recreation | Elk Reintroduction | Community Economic Development

Healthy trees store carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, contributing to the global fight against climate change. Healthier forests along miles of streams within the project will benefit rivers like the Clinch and Cumberland that contain some of the world’s rarest freshwater species.

When TNC’s Clinch Valley Program began sustainable timber harvesting in 2002, we learned we could make forests healthier, more diverse and more resilient to climate change by carefully selecting some trees to cut as part of a conservation plan. The project manages all properties under Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC®) FSC® - C008922 certification global standards that ensure products come from responsibly managed forests that provide environmental, social, and economic benefits.

The project team’s approach to timber harvesting is designed to improve forest health and resilience by creating diversity in the age of trees and in ecosystem structures across the properties. Ensured by our adherence to FSC® principles, harvests typically range in size from four to ten acres and are separated by unharvested retention areas that supply seed sources, provide habitat connectivity and diversity, reduce visual impact on the landscape and conserve water resources. Harvesting activities also support a variety of jobs, enhancing local economies.

Climate change is here now. What we do between now and 2030 will determine whether we can slow warming enough to avoid its worst impacts. By conserving natural habitats and carefully managing forests, we can store billions of tons of living carbon.

The project has an overall goal of sequestering 5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalency (tCO2e) through 2028. During 2022, the forests within the properties sequestered more than 189,000 tonnes of tCO2e, bringing the cumulative total to 4.2 million tCO2e, representing 86% of the project's long-term goal. The project’s carbon sequestration in 2022 is equivalent to taking more than 42,000 cars off the road for one year.

In addition to carbon sequestration, the project continues to advance our work on climate mitigation through the development of eight utility-scale solar projects—some of the first in the Central Appalachian coalfields.

In an innovative collaboration, TNC is working with two renewable energy companies—Charlottesville, VA-based Sun Tribe and Dominion Energy, based in Richmond, VA. The companies were selected in part because of their commitment to community-focused impact and results, including the creation of community benefits plans that will be informed by local input.

When constructed, these solar on mined land sites will occupy approximately 1,000 acres of previously disturbed, former surface mining lands on the Cumberland Forest properties. Collectively, these projects have the potential to generate approximately 130 megawatts of solar power, enough to provide electricity to 22,800 homes every year.

-

Solar Transformation

In southwest Virginia, abandoned coal mines are being transformed into solar installations that will be large enough to contribute renewable energy to the electric grid—a model TNC hopes can be replicated nationwide. Watch the Video

By steering solar development to former mine lands that have been previously impacted, TNC is seeking to minimize development impacts to higher-value forests. The Central Appalachian region is positioned to support the expansion of renewable energy development with hundreds of former surface mines potentially capable of being converted to new solar projects.

These efforts aim to achieve environmental and economic benefits while creating a blueprint for further coal-to-solar transitions across the region, demonstrating that a mission of conservation and economic diversification can be compatible.

If successfully developed, these solar projects will be some of the first solar farms on abandoned mine lands in Appalachia, helping to launch a new chapter in the region’s long history of providing domestic energy. The projects are expected to go to construction and operation in 2025-2029.

The project is also working with state and federal regulatory agencies to remediate abandoned mine land (AML) features that create human safety and environmental problems. AML features are relics of a bygone era before federal surface mining legislation in which mining was either loosely regulated or not regulated at all. This resulted in less-than-ideal reclamation or, in many cases, no reclamation efforts. This is slow, arduous work that requires bringing together many interested partners, but the results are inspiring.

We worked with our partner Green Forests Work in 2022 to complete a 140-acre restoration project in Bell County, Kentucky on previously mined land that brought together many additional partners. Funding was secured from the U.S. Forest Service, the Arbor Day Foundation, Beam Suntory, Artic Express, Angel’s Envy and other Green Forests Work donors.

The restoration included the removal of invasive species on the site and the loosening of soil that had been severely compacted as part of the mining operation. With the site prepared, professional tree planters planted 24 species of native trees, and the planting crew spread 525 pounds of seed for native warm-season grasses and wildflowers across the site. In conjunction with the tree-planting activities, a series of small wetlands and vernal pools were created to offer important habitat diversity and improve water quality.

2023 saw an additional 64,000 trees planted across 95 acres in Leslie County, Kentucky. Planting by professional tree crews was completed in February, with volunteer planting events held over several dates in March.

The lands and waters of the Cumberland Forest offer myriad recreation opportunities, supporting human health and local economic development. Public access is currently available on 59% (149,000 acres) of Cumberland Forest lands. We’re working with partners including public agencies, private hunting clubs, local governments, and recreational authorities to expand access across the property while at the same time seeking to minimize environmental impacts.

On the Highlands property in Virginia, public access to trails is available through a license agreement with the Southwest Regional Recreation Authority (Spearhead Trails). A collection of trail developments were recently implemented near the community of Dante, both for non-motorized cycling and hiking trails, as well as a new off-highway vehicle (OHV) trail to connect Dante to the existing Mountain View Trail system, within the Spearhead Trails network.

TN Wildlife Resources Agency

View the Interactive MapOn the Tennessee portion of the Ataya property, trail use is managed under the public access conservation easement that was conveyed to the State of Tennessee in December 2021. In June of 2022, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA), with input from partners, completed a Public Recreation Management Plan (PRMP) that guides the public’s use of the CF Ataya property for recreation. The property’s first-ever comprehensive plan for off-highway vehicle (OHV) use is part of the PRMP, as well as guidelines for other recreation, such as hunting, fishing, and hiking. The completion of a trail inventory in Tennessee in 2022 resulted in a recommendation of 96 miles of OHV trail to be maintained for public use and identified 17 miles recommended for closure on TWRA trail maps.

In Kentucky, the Wildlife Management Area (WMA) agreement allows for public hunting and fishing, hiking, wildlife viewing, and nature study.

Eastern elk were hunted extensively as European colonizers spread west into the Appalachians; the elk were eventually declared extinct in the nineteenth century. Reintroduction efforts in the region began in the late 1990s, and today there are viable elk herds in Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia.

The project’s properties sit in the epicenter of elk reintroduction efforts in the three states, and the herds have become an important attraction in a burgeoning ecotourism industry.

Communities near the Cumberland Forest have been connected to these mountains for centuries. Appalachian culture—art and crafts, music, food, and folklore—have been enriched by the influences of Indigenous, African, and European traditions. The decline of the coal industry in the region has created a difficult economic situation for many. The project and the Cumberland Forest Community Fund aims to support a response to this decline by contributing to economic diversification through community driven, nature-based industries such as outdoor recreation and renewable energy.

The Community Fund builds on the successes and lessons learned in community-based conservation by TNC's Virginia Clinch Valley Program.

Support for the Community Fund comes from a combination of Cumberland Forest Limited Partnership (CFLP) royalties and generous philanthropic contributions to TNC made by individuals and organizations who care about our work in the Central Appalachians. Grant funding through the Community Fund is available for local projects that enhance economic diversification, build community capacity, and improve environmental quality within the program area. TNC partners with UVA Wise for the management of projects in Virginia, the Clinch-Powell Resource Conservation and Development Council (CPRCD) in Tennessee and the Mountain Association in Kentucky.

Like many land ownership structures in the coalfields of Central Appalachia that have divided estates, the project owns the surface rights of the Ataya and Highlands properties. Unrelated third parties retain ownership of the other subsurface, or underground mineral rights. As stipulated by the property deeds, some mining royalties are paid to the surface owners, CFLP, periodically. The CFLP has committed to providing 100% of these royalties to the Cumberland Forest Community Fund.

The first round of Community Fund grants was made in 2020 and grant recipients since have implemented exciting projects that support outdoor recreation, nature-based economic development, and green infrastructure investment. Over the first four years of the Community Fund, a total of $705,000 has been committed to local projects. This includes $495,000 in royalties and $210,000 in philanthropic contributions. With royalties in decline, and recognizing the growing impact of the Community Fund, TNC plans to broaden its engagement with the philanthropic community to support the Community Fund in the years ahead.

In Virginia, local projects that have received support so far include the Breaks Interstate Park’s rock-climbing program, elk habitat restoration efforts in Buchanan County, outdoor education facilities in several communities, river access points, and a marketing effort by the Clinch River Valley Initiative. In 2024 UVA Wise and TNC will be evaluating and announcing funding decisions for the latest round of Community Fund projects.

In Tennessee, five projects have already been completed including the enhancement of the Hatfield Knob Elk Viewing Tower, the planting of vegetation to prevent riverbank erosion, and the development of new public river access sites for Riverside Rentals. In 2024, TNC and the Clinch-Powell RC&D are evaluating a new round of project applications and expect to announce funding decisions this spring.

In Kentucky, the Community Fund has focused on supporting rooftop solar projects at high-impact sites. Working with the Mountain Association, and after reviewing dozens of options, the Middlesboro Community Center was the first site selected for funding with solar panels installed in 2023. Moving forward, two additional community buildings will receive funding for solar in 2024. Community solar installation projects help deliver long-term cost savings for local governments and community non-profits, while also reducing carbon emissions and providing an outreach opportunity within Kentucky about the benefits and feasibility of renewable energy.

Cumberland Forest Community Fund

Cumberland Forest Project Benefits Communities

The Future: Working at Scale

The project has elements that are local, regional, and ultimately global in scale. It not only seeks to conserve some of the most critical wildlife migration corridors in the eastern states but also aims to support economic diversification in the heart of coal country. With this project, TNC is working at a scale large enough to help ensure that we have a healthy and connected landscape here in the heart of the Central Appalachians in a hundred years and beyond.