Bridging the Gap: Connecting Two Protected Forests in Southern Ohio

The Nature Conservancy is creating the largest tract of protected forestland in Ohio's history.

In the Appalachian foothills of southern Ohio, in Adams County, lies a stretch of road called Sunshine Ridge. Straddling Stout Run and Scioto Brush Creek watersheds, Sunshine Ridge and the surrounding Appalachian foothills that fan outward from it boast iconic Appalachian forest.

Part of the oldest and most biologically diverse forest system in North America, the landscape is composed of mature oak forest stands rising from prominent ridge tops, shrubby deciduous woods and grand, vegetated ravines that clean and control the water levels of nearby creeks.

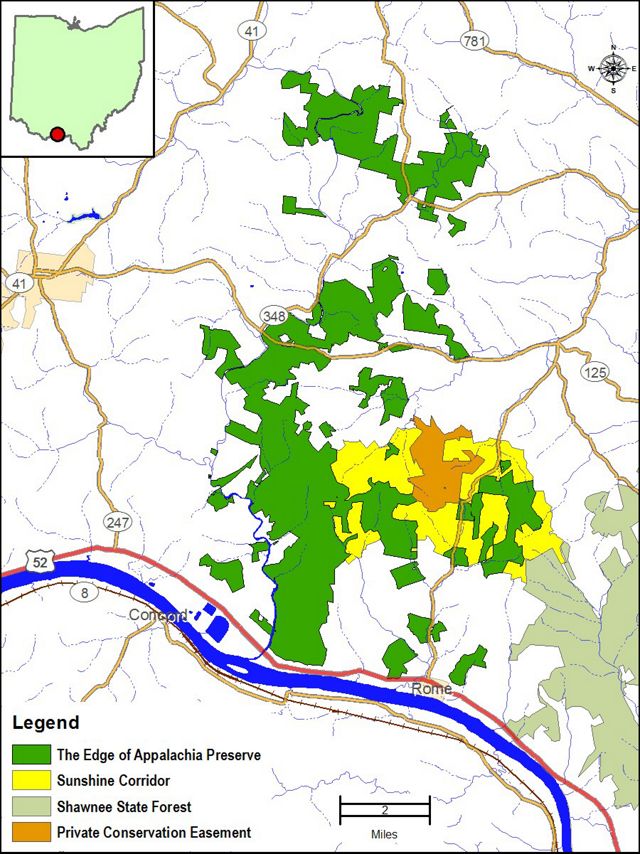

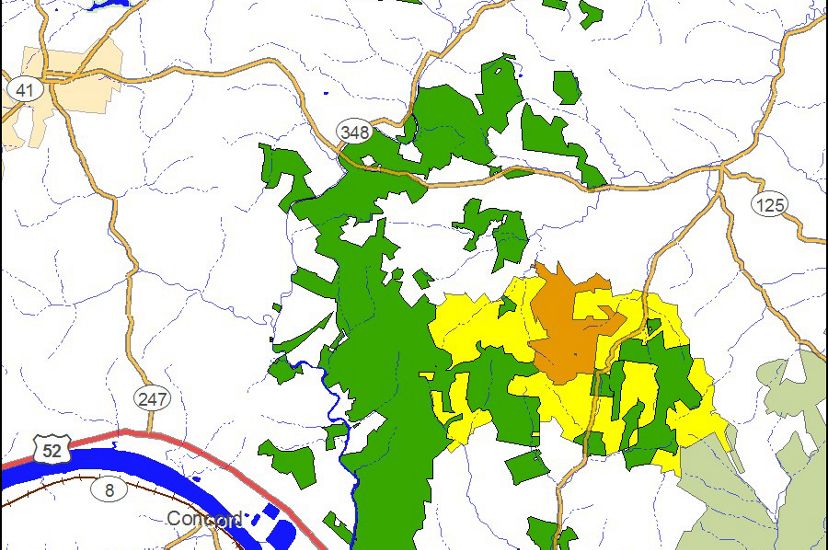

It’s this rich forest habitat that The Nature Conservancy seeks to protect as part of its "Sunshine Corridor" project. The area was selected as a priority for protection not only because of the remarkable biodiversity it harbors, but also because of its strategic location—the 6,000 acres along the corridor link TNC's more than 20,000-acre Richard and Lucile Durrell Edge of Appalachia Preserve System with the 63,000-acre Shawnee State Forest, just some two and a half miles away at their closest points.

Linking these two protected areas will create the largest contiguous, protected forestland in Ohio. As of 2019, The Nature Conservancy is over halfway to its goal, with more than 4,000 acres conserved.

Supporting Wildlife Through Habitat Corridors

Protection of land in the Sunshine Corridor helps create key habitat for rare and endangered species like black bear and bobcat. The area is also important for the migration and nesting of many species of songbirds.

Scarlet Tanager: Habitat corridors help migratory birds. © Scott Whittle

Black Bear: Black bear are endangered in Ohio. © Scott Suriano/TNC Photo Contest 2019

Worm-eating Warbler: Worm-eating warblers are mature forest birds that prefer steep slopes and move into young forest and shrubby areas during portions of its life. © Matt Williams

Bobcat: Connecting habitats helps large mammals like bobcats. © Jeff Wendorff

Why it's Important

In addition to being key habitat for black bear and bobcat, this area is extremely significant for the migration and nesting of many imperiled songbirds including the worm-eating warbler, Acadian flycatcher, Kentucky warbler and scarlet tanager. The rolling Ohio hills support nearly 50% of the cerulean warbler's global populations during the breeding season.

Protecting the Sunshine Corridor will also enhance popular recreational opportunities. The Nature Conservancy is partnering with the North Country Scenic Trail and Buckeye Trail Association to route an estimated 14 miles of trail through the Sunshine Corridor and Edge of Appalachia Preserve System. These trails connect people to protected areas across the state and beyond, contributing to the economic, social and cultural benefits for surrounding communities.

Quote: Martin McAllister

We need to make sure that animals don't get cut off from adjoining habitats, so they can move around in search of food and shelter, and even adjust to temperature increases brought about by climate change.

Threats

While much of the Sunshine Corridor currently is sparsely populated, development pressures loom. By patchworking together protected areas, TNC aims to ensure wildlife doesn't get cut off from adjoining habitats, so that they can move around in search of food and shelter, and even adjust to temperature increases brought on by climate change. In addition to development pressures, unsustainable timber harvesting also is a threat in the region. Properties within the project area contain varying stands of trees. Some show off mature oaks, while others sport mere saplings—the aftermath of a recent lumbering.

Get More Nature News

Get the best nature stories, news, and opportunities delivered monthly.