Jocelyn Runnebaum

Marine Scientist, Maine

Maine

Jocelyn Runnebaum Jocelyn is Marine Scientist for The Nature Conservancy in Maine. © Phoebe Parker

Areas of Expertise

Fisheries management, participatory research, habitat modeling, coupled natural and human systems

Biography

Jocelyn’s work focuses on helping to advance TNC’s marine conservation initiatives in the Gulf of Maine and nationally. Jocelyn works collaboratively with university scientists, resource managers and industry partners to improve the overall ecological health of the Gulf of Maine. This work includes partnerships to implement on-the-water projects to understand the habitat value of seaweed aquaculture; a regional survey to understand fishermen’s perceptions of the impacts of climate change on their businesses and fishing communities; and working to influence ocean and coastal policies at the state, regional and national level.

“Marine resources are a critical aspect of Maine’s culture and economy. The conservation and sustainable use of marine resources is critical in sustaining these aspects in addition to a healthy ecosystem.”

Before joining TNC, Jocelyn worked for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game as a Fisheries Biologist providing technical support and advice on federal fisheries management. Jocelyn has a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology from Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, TX and a Ph.D. in Marine Biology from the University of Maine in Orono. Before earning her Ph.D., Jocelyn commercial fished for salmon in Alaska, trained sled dogs for an Iditarod musher and was a Peace Corps volunteer in Zambia working with fish farmers.

- Switch to:

- Commentaries

- Publications

- Maine Stories

April 25, 2022

Factoring Climate into Fisheries Management

Climate change is damaging the ecological health of the Gulf of Maine right now. While significant changes in ocean temperatures have caused shifts in species distribution across the globe, the waters off Maine’s shores are warming two to three times faster than the global average. Bottom temperatures measured during the Fall have increased 0.8°C in this region over the past 45 years.

Many fish and invertebrate species targeted by commercial fisheries are either shifting North or into deeper waters because of changing ocean conditions. These shifting distributions have significant implications for many natural resources and users, including regional fisheries. The movements may limit traditional fisheries for one area while creating new fishing opportunities in others.

So, what does this mean for the people who fish for a living?

Since 2020, I’ve been working with colleagues from The Nature Conservancy, the University of Washington, and the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada to explore how commercial wild seafood harvesters in New England perceive the threat of climate change and its impact on fisheries.

Our work has culminated in a new report we recently released titled Climate Change: New England seafood harvesters’ perceptions of the impact on fisheries, vulnerability, and wellbeing.

The report summarizes the responses to a survey completed by four hundred commercial fishing permit and license holders in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. We asked how harvesters feel about the current state of their fisheries, regulations, climate change, and their confidence, or lack of confidence in the future of their fishing businesses.

We developed a vulnerability index based on harvesters’ perceptions of 1) their exposure to climate change, 2) how sensitive they are to those changes, and 3) their ability to adapt. At one end, a harvester may be impacted by climate change and feels they can do little about it. At the other, they feel that either they are not impacted or have ways to adapt.

Interestingly, 72 percent of respondents believe climate change is occurring, but just 53 percent believe climate change will harm them personally, and only 28 percent believe they have already seen a negative impact on their ability to catch fish. Climate change is perceived as being a slow moving and distant threat unworthy of timely action. However, climate change is a threat multiplier, exacerbating already existing challenges like those identified by harvesters in this report. These challenges may be further amplified by a changing environment and therefore must be considered in climate adaptation planning.

This report is part of a larger effort at TNC to work towards more climate resilient fisheries. TNC is advancing science to understand climate impacts to fisheries and ecosystems, using technology to streamline data collection and respond more quickly to changes on the water, and leveraging partnerships to garner more resources for adaptation strategies to protect ocean health.

This report illuminates the necessity of addressing climate change alongside other concerns that harvesters perceive as more immediate and pressing, including tension around fisheries regulations, market access, and shrinking access to a working waterfront.

While humans have limited emotional capacity to respond to potential threats, fisheries are currently being impacted by climate change and action needs to be taken to address these impacts. Integrating climate change into every aspect of management–and talking about how climate policies promote overall ecosystem health–is critical for sustainably managing fisheries into the future.

June 2021

Studying the Benefits of Kelp

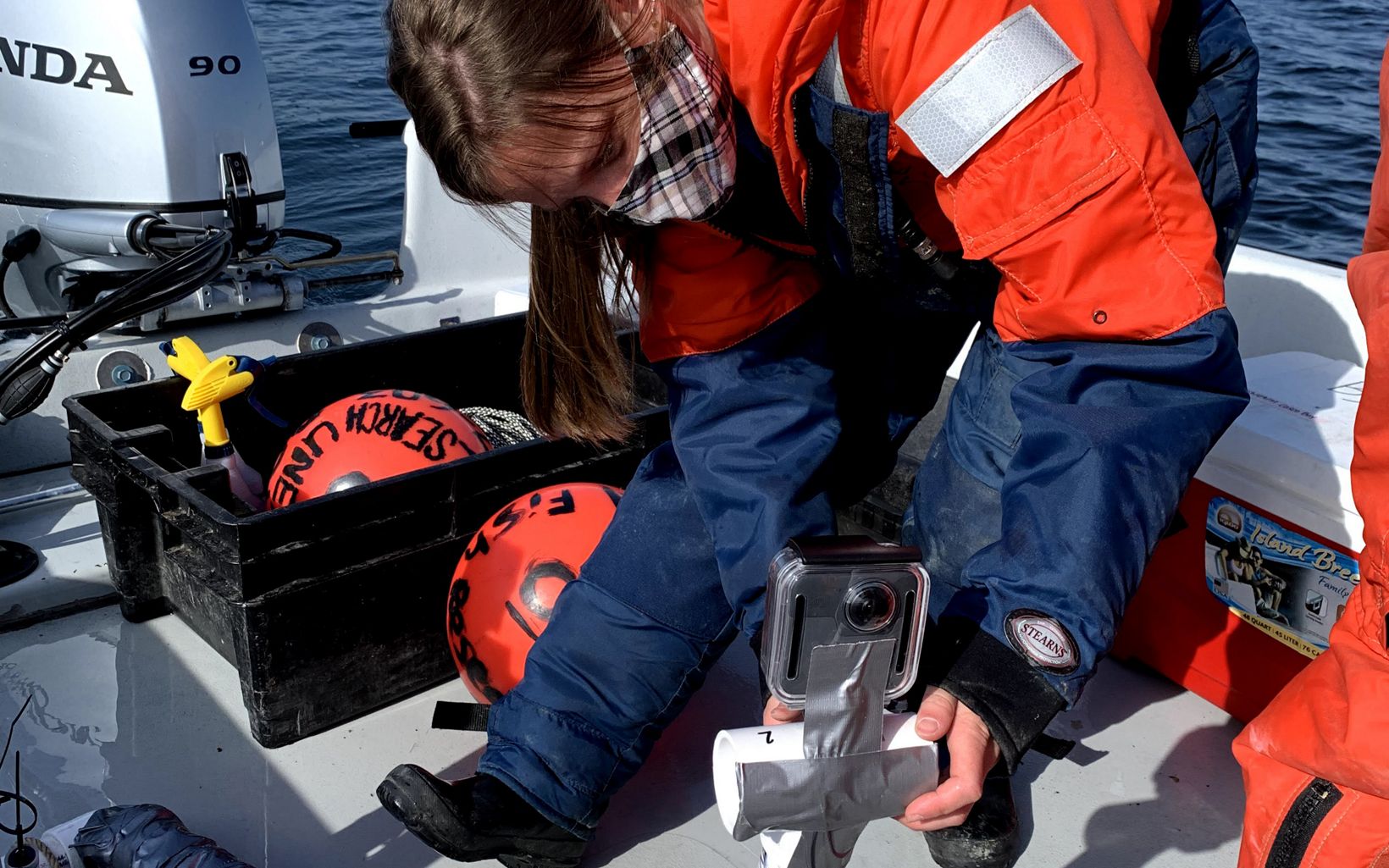

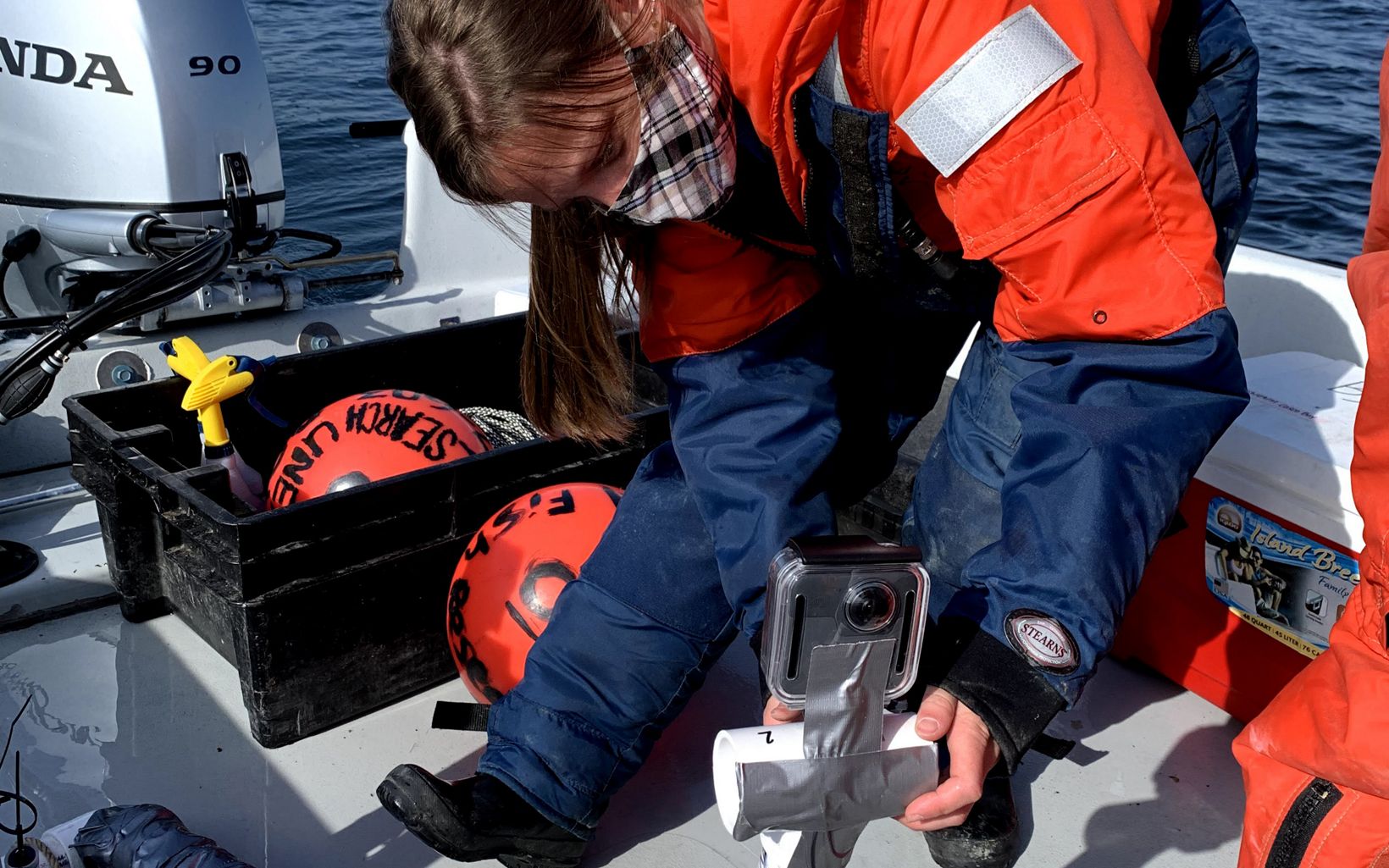

On a windy Friday afternoon in early May, I joined Dr. Carrie Byron and Emilly Schutt from the University of New England (UNE) for an afternoon kelp-sampling trip. The three of us donned dry suits and masks and ventured out by boat to set GoPro cameras around the UNE kelp farm, with the goal of capturing video footage of how fish and invertebrates interact with the kelp.

Next, we took water samples from the farm sites to collect environmental DNA from these same areas. The research team wants to know if there are more species that associate with the kelp farm than outside of the kelp farm. Some of this work is also being done on commercially operational kelp farms in addition to UNE’s farming sites.

This trip was part of an exciting new partnership between The Nature Conservancy, The University of New England, and the University of Auckland. Together, these organizations have launched a collaborative effort to understand the effects of kelp production in temperate climates, and to learn from sites located on opposite sides of the world. Dr. Carrie Byron and Emilly Schutt are leading the field research in Maine.

Kelp is a winter crop, typically harvested in late spring. It does not require feed or freshwater inputs and has low carbon emissions. For humans, kelp is high in fiber, vitamins, and minerals like Vitamin C, Vitamin K, calcium, zinc, iodine, and magnesium. And for nature, kelp farming is of particular interest to us because of its potential to provide a variety of ecological services, including nitrogen removal, carbon capture, and habitat provision for various marine species (Gentry et al. 2019).

In Maine, a burgeoning kelp farming industry is now the U.S.’s largest producer. This could have big implications for the global food market, where food production is a major source of habitat degradation, carbon emissions, and freshwater usage. Some food systems, like kelp, may be able to minimize that environmental impact while also providing benefits to the ecosystem. That’s why the Nature Conservancy is working with partners across the globe to identify and demonstrate the potential for regenerative food systems on land and in the sea.

Given the need to help restore the Gulf of Maine marine ecosystem, we are excited about the new partnership, and looking forward to working with researchers, industry, and local communities to investigate the potential benefits and impacts of kelp farming on marine life!

Scenes From a Study Area

Li, G., J. Cao, X. Zou, X. Chen, and J. Runnebaum. (2016). Modeling habitat suitability index for Chilean jack mackerel (Trachurus murphyi) in the South East Pacific. Fisheries Research, 178, 47-60. DOI: 10.1016/j.fishres.2015.11.012

Ebel, S., Beitl, C., Runnebaum, J., Alden, R., & Johnson, T. (2018). The power of participation: Challenges and opportunity in facilitating trust in cooperative fisheries research in the Maine lobster fishery. Marine Policy, 90, 47-54. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.01.007

Runnebaum, J., L. Guan, J. Cao, L. O’Brien, and Y. Chen. (2018). Habitat suitability modeling based on a spatio-temporal model: an example for Cusk in the Gulf of Maine. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 75 (11), 1784-1797. DOI: 10.1139/cjfas-2017-0316

Runnebaum, J., E. Maxwell, J. Stoll, K. Pianka, N. Oppenheim. (2019). Communication, Relationships, and Relatability Influence Stakeholder Perceptions of Credible Science. Fisheries, 44 (4), 164-171. DOI: 10.1002/fsh.10214

Runnebaum, J., K. Tanaka, J. Cao, L. Guan, and Y. Chen (2020). A prediction of bycatch hotspots based on suitable habitat derived from fishery-independent data. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 641, 159-175. DOI: 10.3354/meps13302

Hodgdon, C.T., K.R. Tanaka, J. Runnebaum, J. Cao, Y. Chen (2020). A framework to incorporate environmental effects into stock assessments informed by fishery-independent surveys: a case study with American lobster (Homarus americanus). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 77 (10), 1700-1710. DOI: 10.1139/cjfas-2020-0076