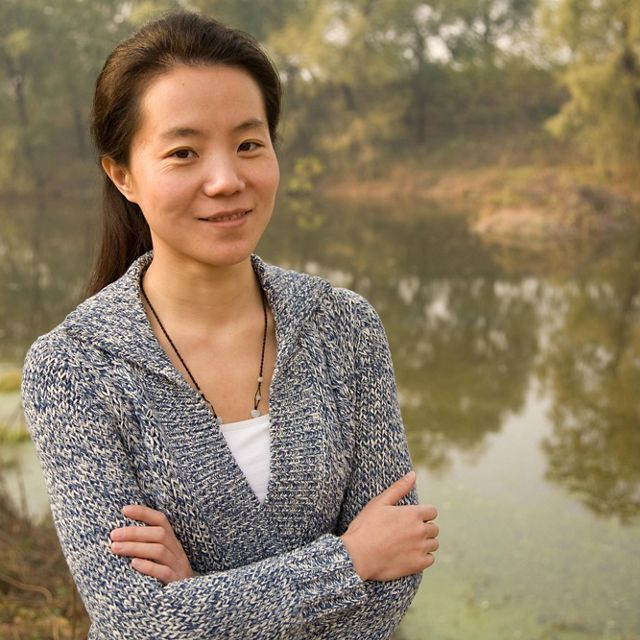

Dr. Qiaoyu Guo is a technical advisor on The Nature Conservancy’s global freshwater team. Qiaoyu is from Qinghai Province in China, which spreads across the rugged Tibetan Plateau and contains the headwaters of the Yangtze River.

Four hundred million people—more than the population of the United States—depend on the Yangtze River for freshwater. The Yangtze is Asia’s longest river, and its rushing waters are electrifying the world’s fastest-growing economy.

When Qiaoyu first learned how important the Yangtze River is for China’s economy and for providing freshwater for wildlife and people, she was inspired to dedicate her career to protecting it.

Nature.org recently spoke with Qiaoyu about the Conservancy’s past and future addressing conservation in the Yangtze River Basin.

Nature.org: How did the Conservancy’s work on the Yangtze River start?

Qiaoyu: When the Conservancy began our Great Rivers Partnership 10 years ago, we selected the Yangtze as one of the eight rivers around the world where we would focus our conservation efforts. The Yangtze is the world’s third longest river and it’s the biggest river system in Asia, but the most important thing is that the biodiversity of this river is very high. For these reasons, the Yangtze has long been an important component of our worldwide Great Rivers network and our global freshwater work.

Nature.org: What were some of the first ways we addressed conservation on the Yangtze?

Qiaoyu: We began our work on the Yangtze by using the knowledge we’ve developed in the U.S. to help our partners in China practice environmental flows—a way to release water flows from dams so that they mimic natural river flows needed to sustain fish populations. For example, for five years in a row, we’ve worked with the China Three Gorges Corporation to release flows from the Three Gorges Dam that mimic the Yangtze’s flood pulse in order to promote carp spawning. We also work with China Three Gorges to design environmental flows for the Lower Jinsha Cascade, which is the upper stream of the Yangtze.

The Conservancy also has a partnership with the Yangtze River Fisheries Management Commission and the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture focused on sustaining fisheries in the Yangtze. We’ve invited experts from the U.S. to China to help Chinese partners to understand how to monitor freshwater ecosystems and how to implement conservation actions based on their monitoring results.

These collaborations have been going on for 10 years and we are still doing all these things. Today our biggest focus is on sustainable hydropower development across the basin. Hydropower is an important issue for people in China, and sustainable hydropower is an important strategy for the Conservancy’s work to address freshwater challenges worldwide.

Nature.org: How do we make a difference on how hydropower is developed in the world’s most populous country—where hydropower offers an important alternative to high-carbon energy sources but can still be very harmful to freshwater biodiversity and people?

Qiaoyu: We’re using a strategy we call Hydropower by Design. Our work in the Penobscot River in Maine is an example. There were many small dams on the Penobscot, but the local community and government wanted to restore the river’s ecosystem. So the Conservancy helped them remove some of the dams and open the river to fish. But they have still maintained hydropower capacity for the whole river system by increasing hydropower in some areas to allow dam removal on more important areas. This is Hydropower by Design. It’s a comprehensive, basin-scale approach.

Here’s one example in the Yangtze. The Three Gorges Corporation has a series of dams on the lower Jinsha River, which is part of the upper Yangtze Basin. On this tributary of the Jinsha called the Heishui River, the Chinese government wants to do what we did on the Penobscot. There are one or two dams on that river already. They might remove the dams or create fish passage, and they want to create a conservation reserve on the Jinsha River. My team is involved to help introduce our successes—our Hydropower by Design methodologies in the U.S that show how to conserve freshwater ecosystems by picking out the most important areas to protect.

Nature.org: Three Gorges is the largest hydropower company in the world and one of our high-profile partners. Does our work with large-scale hydropower companies go beyond Three Gorges?

Qiaoyu: Yes. Last year, the Conservancy launched the Center for Sustainable Hydropower, based in Beijing, to help us influence hydropower development around the world. The Center can help us assess opportunities to work with different hydropower companies and with different government agencies. Our goal is to work with all of the big decision makers, all the policy agencies. The Center is trying to help China and all hydropower developers to have better policies on environmental issues and to communicate ideas with each other.

Nature.org: How do you see our work in the Yangtze evolving?

Qiaoyu: We’ve had some good news recently. The President of China—Xi Jinping—announced he would like to build a greener Yangtze River Basin, focusing more on conservation. He’s definitely the highest leader to talk about river conservation, so it may be better news compared with the past. We are thinking about how we can adapt our strategies in the Yangtze to take advantage of this opportunity. We want to go back to something that we have talked about in the past—how to set up a conservation fund so that revenue from hydropower can fund conservation across the whole basin, so we are not only working on issues related to the sustainable operation of levees and big dams.

For example, we can think about how to rezone wetlands or lakes to provide a flood retention function. There are a lots of wetlands and lakes in the middle and lower Yangtze, which store water from the main river channel when levels are high and have naturally limited flood risk in past. But in recent years, most of these wetlands have been changed to farmlands. We should use this chance to think about how to restore these wetlands and lakes and their natural flood retention functions to set up a more flexible and reliable flood risk management system for the Yangtze River.

Nature.org: You grew up near the Yangtze’s headwaters, so I’m curious to hear your personal perspective. Why are you excited about our work on the Yangtze?

Qiaoyu: The reason why I am excited to work on the Yangtze and why it is so urgent to work here is that the Yangtze is a very important economic driver for all of China. This includes hydropower and navigation. Also, traditionally, it is very important for agriculture. That’s irrigation and a lot of water use with a heavy population along the river. So, even though the river’s water quantity is very huge, the water quality is still very poor for the whole basin. I’m worried about the river—the water quality and also the biodiversity. I believe it is very urgent for us to work here.