Taking Flight in Aotearoa New Zealand

By Ethan Kearns, Coda Fellow and Videographer

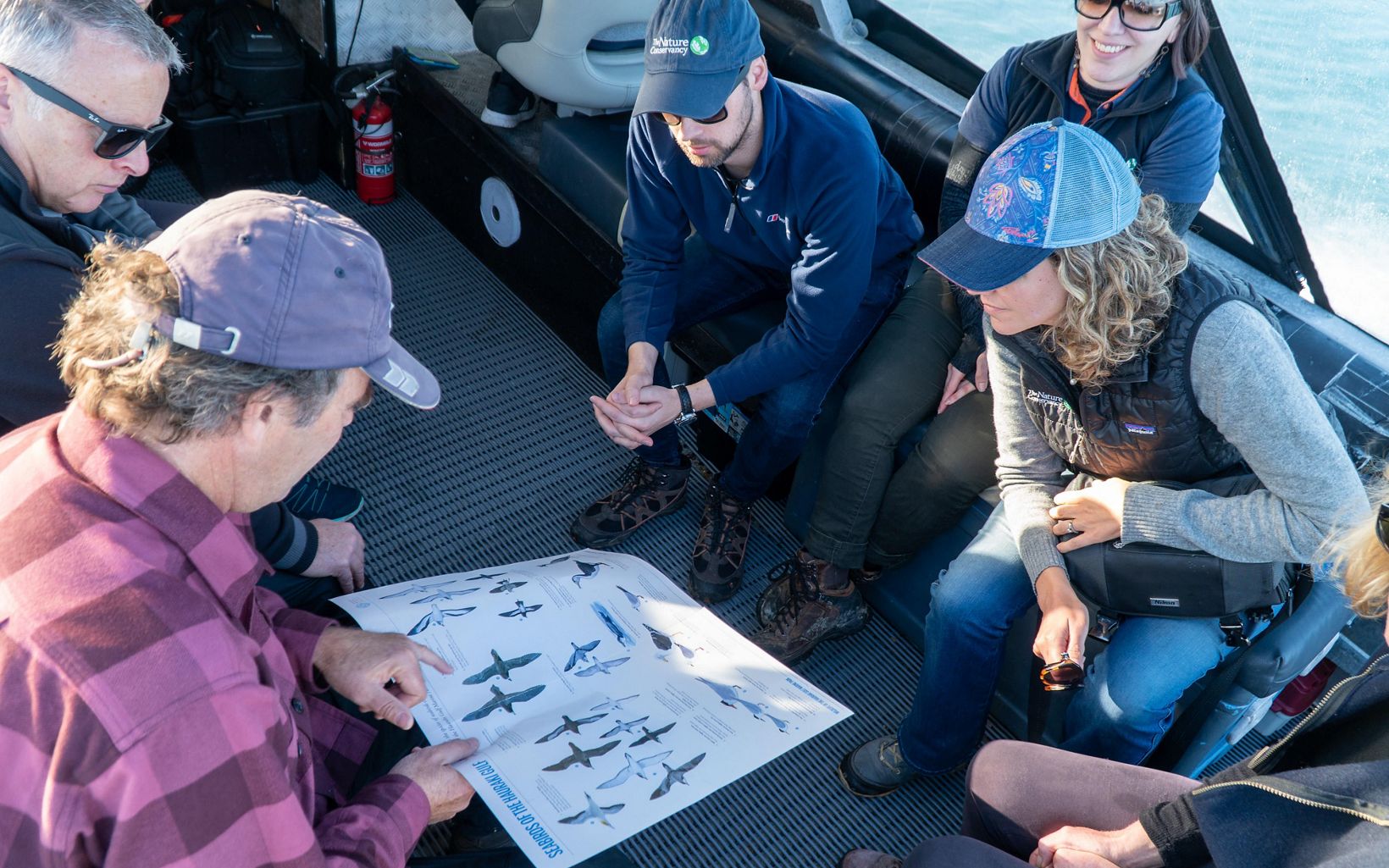

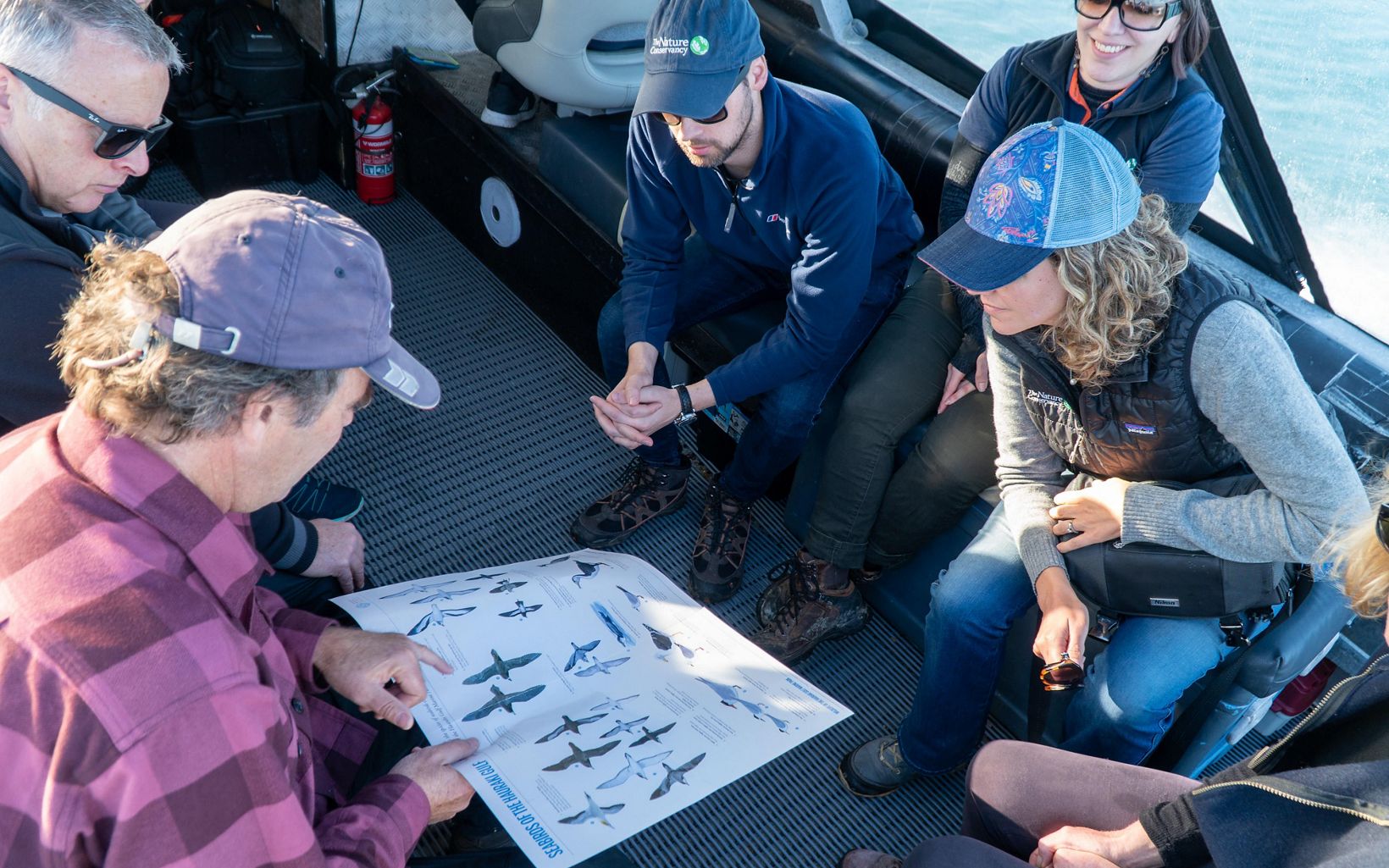

HOLDING MY CAMERA GEAR HIGH OVER MY HEAD, I JUMP from the boat into chilly seawater almost waist-deep and start wading ashore. I’m lucky enough to be visiting a privately owned island in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Hauraki Gulf with The Nature Conservancy’s Aotearoa New Zealand director of conservation, Carl McGuinness (now Deputy Country Director). This place is wild: thick forests stretch from beach to cliff, and invitations to visit are rarely given.

We’ve come to Otata (an island in a chain called The Noises) because it may hold clues for McGuinness’ work. He is leading TNC’s efforts with local partners to restore mussel beds and improve water quality across the 1,500-plus square miles of seabed that surround us in the Tīkapa Moana/Te Moananui ā Toi (the Māori names for the Hauraki Gulf).

Quote

Dad never needed any extras. He taught us to only take what we need.

As we dry off on the rocky beach, our host, Sue Neureuter, welcomes us to her island. She shares some of her homemade ginger crunch, a traditional Kiwi snack, and tells us a bit of family history. “The Noises are very, very precious islands to us and have been part of our family for over 90 years. I used to come here as a kid with my parents. Dad never needed any extras. He was an absolute conservationist. He taught us to only take what we need.”

As she speaks, a Buller’s shearwater glides overhead on the sea breeze, and a pair of tōrea pango (variable oystercatchers) feed on mussels in tidal pools.

Snacks finished, Neureuter leads us into the island’s interior, passing beneath old-growth trees and around seabird nesting areas. As we move through the network of trails I stop to look into a deep hole in the ground. Neureuter says that many of the seabirds that live here return to their subterranean nests every season. The nest looks so defenseless. It amazes me to think that the chicks born here can grow up to fly across thousands of miles of open ocean. This place is so special.

“I think of my childhood with the noise from the penguins and the gulls and the white-fronted terns,” she says. “But like many islands in this area, the bird population on Otata was devastated by the introduction of predators, in this case, rats.”

I find it hard to believe that this place could feel more alive. Standing there in a forest that seems so full of sound, I try to quadruple the amount of bird chatter in my mind.

Aotearoa, New Zealand calls itself the seabird capital of the world. Eighty-eight species of seabird breed on its islands; one fifth of the world’s seabird species use this very gulf.

That’s in part thanks to people like Neureuter and her family, who have worked hard to keep seabird habitat intact. With the help of other conservation partners, she says they have managed to remove the invasive rats that fed on the birds’ eggs. “Since the rats have gone, the islands have become vibrant with life again,” Neureuter says.

As we loop back towards the beach we pop in and out of forest onto cliffsides where seabirds perch high above fur seals sunbathing on the rocks below. Neureuter can navigate the twists and turns of her paradise in her sleep, but with my tripod and cameras I often find myself lagging behind. At times I stop uncertainly at the middle of an intersection, several paths dissecting the forest in front of me, distracted by the melodic chorus coming from the dozens of Tui—an endemic bird whose song bears resemblance to R2D2 in Star Wars.

The Call of a Tui Bird

An endemic species that can be found throughout Aotearoa New Zealand, the Tui can imitate sound much like a parrot and has two small white tufts of feathers at its neck.

As Neureuter walks along, she shares memories of a childhood filled with seabirds, kekeno (New Zealand fur seals), giant wētā, endemic birds and a plethora of marine life.

Her family’s efforts on land seems to have had a positive spillover effect into the coastal marine habitat. McGuinness tells me the island is ringed by mussel beds that are healthier than other places around the Hauraki Gulf. One theory is that protecting bird habitat prevents soil runoff from killing mussels. Still, Neureuter is keen to use Otata as a test bed for research on marine restoration.

Quote

These beds provide a valuable learning opportunity. This knowledge can be used to guide restoration of lost mussel beds.

"These beds provide a valuable learning opportunity. This knowledge can be used to guide restoration of lost mussel beds," McGuinness says. TNC and its partners are investing in research because mussels help clean the water through their filtering activity—and that’s something the gulf needs. “If we can determine the ingredients for successful mussel bed restoration, then we will be positioned to scale restoration efforts.”

As the sun sets and we head back, a rainbow arcs over the gulf and seabirds speed along the water’s surface.

Behind me, The Noises disappear into the vast gulf, and I can’t help but marvel at the magnitude of the transformation that McGuinness and TNC’s partners want to create. It’s all new territory and new research. Still, I am leaving with high hopes, knowing that TNC and its partners are determined to make a big difference for the epicenter of the seabird world.