Community Resilience Building

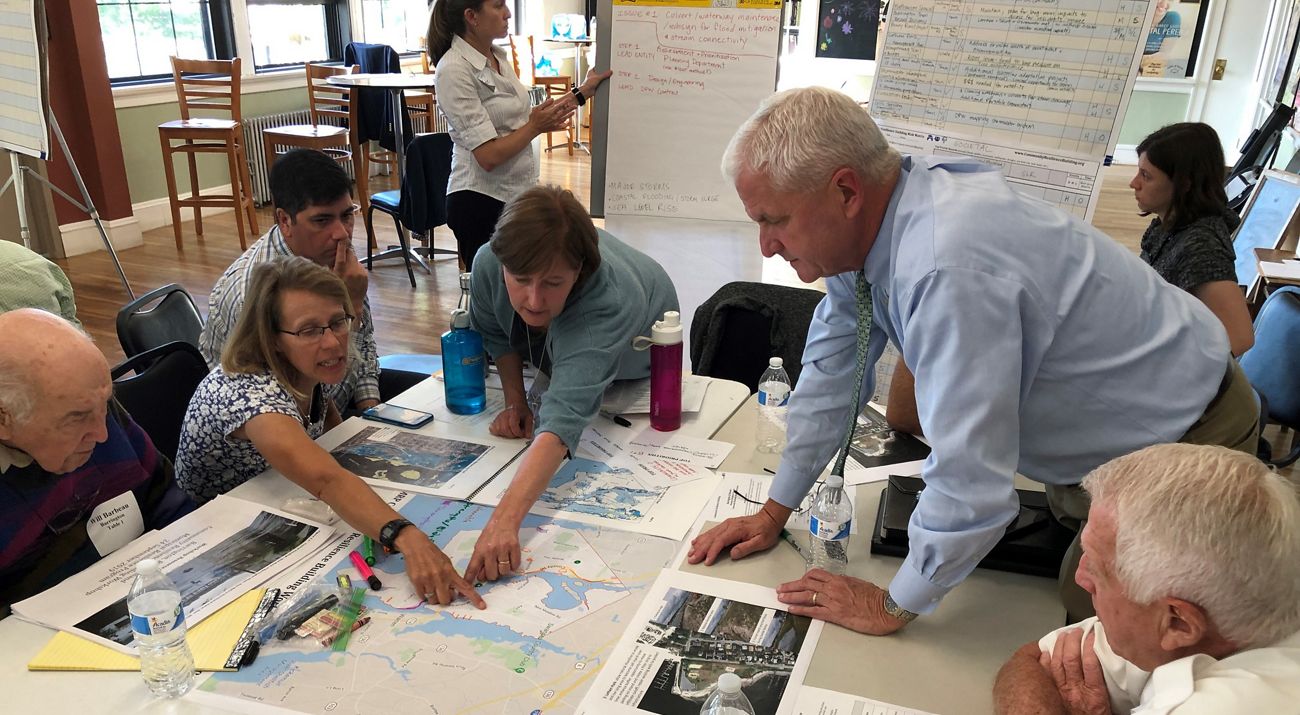

A program helps communities - in Connecticut and beyond - build resilience in the face of extreme weather and climate change.

We all know the old adage about New England. “If you don’t like the weather, wait five minutes, it’ll change.” That’s never felt as true as it does now, except that might mean hail in August or flooding in December. How can communities protect their residents amid a changing climate when everything feels unpredictable?

The Community Resilience Building (CRB) process, created and managed in Connecticut by The Nature Conservancy since 2009, is helping to make that possible for people and nature. TNC's Director of Science in Connecticut, Adam Whelchel, shares more.

TNC: How are communities looking at the issue of resilience given this year’s momentous weather events?

Adam Whelchel: Towns and cities here in Connecticut and across New England are hyper-aware of the issues linked to climate change because municipal staff and residents are dealing with it on a regular basis. It has become a much more prevalent issue since we launched CRBs back in 2009 largely because residents are suffering and things cost so much money to repair or replace, and you don’t want to spend twice. So a lot of the actions that are collaboratively created in CRBs are to take care of things we already know are issues, and assess, identify and prioritize actions that empower communities with an agreed upon path forward and circumvent the all-too-common “stuck in a merry-go-round” mentality.

TNC: Were CRBs initially intended for the coastline, where people have seen a lot of change?

Adam Whelchel: The process was designed at first to pull a community together around TNC’s Coastal Resilience decision support platform so they could look at the data, figure out how their community was vulnerable to coastal hazards (such as storm surge and sea level rise) and prioritize actions to enhance resilience (such as nature-based solutions). However, climate is changing everywhere, so TNC developed CRB as a process that can go anywhere: it’s inland, it’s coastal, it’s wealthy communities, it’s under-served areas. We identified climate change as something we need to take action on to help reduce impacts not just for nature, but for the people who benefit from nature. And now we’ve been doing that over the last 15 years with over 500 municipalities and academic institutions across 14 states, to date.

TNC: What are common areas of concern when a municipality asks TNC for a CRB?

Adam Whelchel: Interestingly, one of the top concerns consistently centers around the dependence of many communities on volunteerism. A lot of communities, particularly those that are rural, are run by volunteers (boards, commissions, committees, helping out in food pantries and the library, supporting and caring for those at shelters, and in a crisis, volunteer fire departments). Without volunteers the fear is that many community-based services, resources and needs go unmet.

Stormwater management is also universal: What do we do with all this water, especially coastal communities with water on all sides (inland, coastal flooding, higher ground water levels)? Next up is often a focus on risks to infrastructure like bridges, roads, culverts, pump stations and low-lying facilities such as wastewater treatment plants. With CRB, we ask the communities to be more wholistic and include discussions about societal needs and public health, which is helped by the inclusion of social services, health districts and the faith-based community. CRB also requires the community assembled to discuss not only infrastructure and societal needs, but the environment as well. The value of open space and natural systems is always front and center, and there’s a huge amount of universal respect and appreciation for natural resources in every CRB.

TNC: Have you conducted these beyond Connecticut?

Adam Whelchel: I’ve worked with communities as far away as the San Francisco Bay in California, 20+ municipalities in the greater Milwaukee, Wisconsin area, academic institutions in Atlanta, Georgia and in vulnerable communities like Block Island (Rhode Island), all of Cape Cod, Nantucket and Marthas Vineyard in Massachusetts, as well as rural communities with less than 5,000 residents in places like Maine, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Vermont and the Hudson River Valley in New York.

Impact at a Glance

-

8

million people in 14 states covered as of 2025

-

500

municipal and academic institutions from around the country

-

1.8

million Connecticut residents benefiting from the program

TNC: What are some solutions that communities have implemented?

Adam Whelchel: In 2017, I was invited to co-create, launch and manage a new program called the Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness (MVP) program for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts with the Governor’s Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. The then-governor and the state team assembled was saying, “We need to help our municipalities become more resilient in order to be a more resilient state.” To do that, all 352 municipalities were offered the ability to partake in the required planning step of completing a CRB to get enrolled in the MVP program. Once their respective CRB was completed, priority actions identified through the process could be advanced for MVP actions grants.

The MVP program effectively linked resilience planning with action via the CRB process. Since 2017, 99% of the 352 municipalities have completed their CRBs (or have been grandfathered into MVP), and more than $150 million in state funds have been allocated to advance over 168 priority action projects with most involving nature-based solutions. The list of projects is just an unbelievable triumph for nature with countless benefits to people and ecosystems through dam removals, floodplain forest restoration, salt marsh enhancement, and countless improvements to tree canopy and parks in urban spaces across Massachusetts. In short, over 6 million Massachusetts residents are now being served by climate action plans (along with 168 projects) generated via the CRB process.

TNC: Can similar programs develop in other states?

Adam Whelchel: MVP has been so successful that we replicated the process in Rhode Island where all but one of the 39 municipalities has completed their CRBs since 2019 with over $25M awarded for nature-based priority action projects, to date. TNC’s Connecticut and Rhode Island programs partnered to set up, launch and manage the statewide Rhode Island Municipal Resilience Program.

TNC: What’s next for the CRB process?

Adam Whelchel: The CRB process has already served so many communities that word-of-mouth regarding how well the process works is spreading across the United States. For example, in 2024 we had the privilege of bringing CRB to the City of Lebanon and the Town of Hartford for the first CRBs in New Hampshire and Vermont, respectively. The Facilitation Team for these CRBs included TNC staff from Connecticut, New Hampshire and Vermont. We were joined by team members from the University of New Hampshire – Extension and Dartmouth College. These CRBs had such an incredible feel of community and collaboration that I have no doubt it will continue to make a difference in the Upper Valley region and across the Northern Appalachians going forward. I also see continued engagement with academic institutions as influential places of learning, with the hope of instilling community resilience-building practices and action-taking to combat climate change in the next generation of leaders as they graduate from these places of high learning. We are working currently with Georgia Institute of Technology (Atlanta), Occidental College (Los Angeles), and Wake Forest University (Winston-Salem, NC) with more and more interest from other communities.

Quote: Adam Whelchel

It all helps to ensure the environment is part of a resilient future for these communities. Without a planning process like this, it would be about bridges and roads and infrastructure. CRB enables people and nature to be part of the vision. And it creates an army of conservationists to do it.

TNC: What do you see long into the future for the CRB process?

Adam Whelchel: Our hope is that CRB can continue to be a constructive process for communities across Connecticut and the United States to improve resilience and sustainability in an inclusive and caring manner where infrastructural needs are considered in accord with societal and environmental needs and benefits. This issue is not going away, and an absolutely solid step forward is to gather and take strength in the power a community coming together to collaboratively create a climate action plan. CRB has successfully done that for over 500 communities to date, and I would love to see that number grow to over 1,000 very soon because ultimately, those communities that take the time to envision a more resilient future will be stronger going forward. CRB provides that message of hope and advantage to those willing to ask for help.