We’re helping to restore wetlands for healthy and resilient coral reefs and coastal communities.

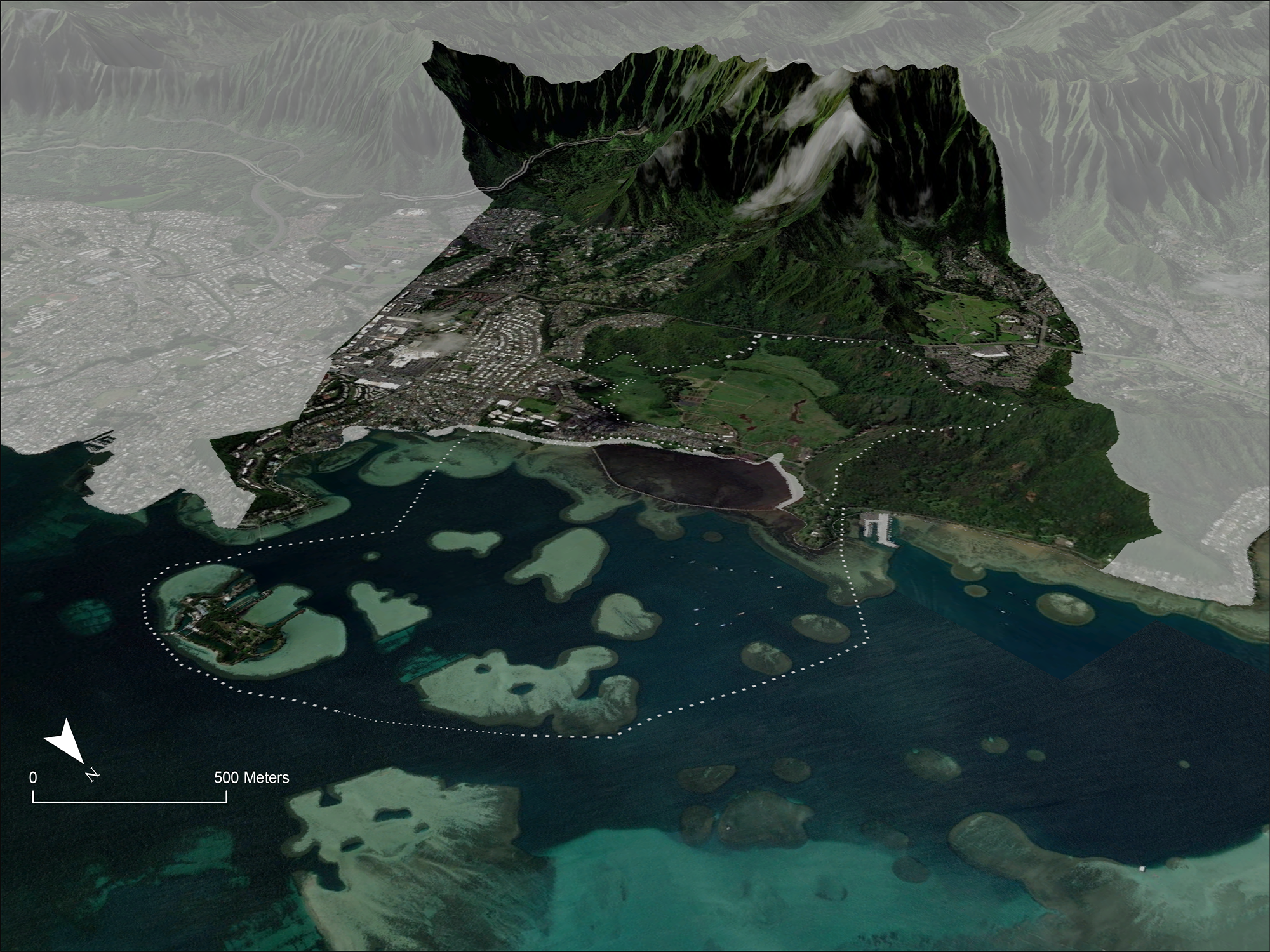

Restoring natural water flows and mauka-makai (mountain-ocean) habitats is essential to building community and coastal resilience and ensuring that Hawaiian culture and species thrive.

Project and Partners

The Koʻolaupoko Hawaiian Civic Club initiated the effort to restore Heʻeia ahupuaʻa (land division), which spans an entire watershed. Multiple groups, including some led by a new generation of native Hawaiian leaders, have joined forces to restore health and abundance to Heʻeia’s upland forests, wetlands and coastal fishpond through the perpetuation of traditional practices. In 2017, Heʻeia was designated the 29th site in the National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) System.

Papahana Kuaola

Papahana Kuaola, a grassroots non-profit, works to restore stream and forest health in the Heʻeia uplands, with help from its many volunteers. Visit their website to learn more about their efforts to perpetuate Hawaiian ecosystems and culture.

Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi

The locally led Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi formed to restore abundance and perpetuate Hawaiian culture, farming and wildlife in the Heʻeia wetlands. Visit their website to learn how their local produce, educational programs and workdays nourish bodies and minds.

Paepae O He‘eia

Established by a group of young Hawaiians, Paepae O Heʻeia is dedicated to restoring and managing the ancient Heʻeia fishpond. Visit their website to learn more about their efforts to perpetuate culture and provide sustenance for the community.

Since 2008, TNC has been working in partnership with Kākoʻo ‘Ōiwi to restore He‘eia’s wetlands. We also contribute to NERR research to help demonstrate the socio-cultural and ecological benefits of traditional management.

How TNC Helps

After working with the Division of Aquatic Resources to remove invasive algae smothering Kaneʻohe Bay reefs, TNC joined forces with Kākoʻo ‘Ōiwi to restore the wetlands and loʻi kalo as a way to reduce sediments that flow into the bay and propel algae growth.

With TNC support, Kākoʻo ‘Ōiwi has:

- removed mangrove trees and other invasive vegetation that clogged streams and replanted native vegetation,

- restored a system of loko wai (waterways) and ‘auwai (irrigation channels),

- replanted loʻi kalo, ulu (breadfruit), mai‘a (banana) and other traditional crops, and

- worked with partners to develop a Conservation Action Plan to guide their work.

Now, Kākoʻo ‘Ōiwi is re-establishing māla (gardens, cultivated fields) and food forests where culturally and biologically important plants will be cultivated for harvest and use. They will begin replanting once the invasive trees and vegetation are removed from the fenced and pig-free 20-acre area.

TNC also conducts research on watershed hydrology, freshwater fish presence and abundance, nutrient transport through the wetland and soil erosion rates in the surrounding hills.

Impacts and Benefits

Biological and Ecological

As a result of the collaborative efforts, fresh water is once again flowing through the wetlands, nourishing loʻi kalo and providing habitat for freshwater species, including native fish and plants and endangered native waterbirds.

Climate

Healthy wetlands and fishponds absorb excess sediment-laden runoff during heavy rains, providing vital flood protection for coastal communities and preventing excess sediments and nutrients from reaching ocean waters and reefs.

Demonstrating wetland effectiveness at Heʻeia—a highly visible and easy to access site—can help build support for adopting the cost-effective natural climate solutions needed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Socio-Cultural

Kākoʻo ‘Ōiwi employs more than a dozen farmers, processes the kalo it grows at its newly constructed poi mill, and supplies local residents and restaurants with poi and fresh produce.

The farm also serves as a living classroom, providing hands-on educational programs for youth and families to learn about Hawaiian cultural practices and the traditions that sustained kanaka maoli (Hawaiian people) for centuries.

The traditional and collaborative approach to stewardship in the Heʻeia ahupuaʻa—guided by Native Hawaiian philosophies and values and complemented by NERR research—is creating a robust model for building resilient ecosystems, economies and communities.

Learn more about our science, restoration and how we help strengthen conservation management and leadership so Hawaiʻi's reefs can support healthy fisheries and prosperous communities long into the future.

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Hawai’i & Palmyra. Get a preview of Hawai’i & Palmyra’s Nature News email.

Find More Places We Protect

The Nature Conservancy owns nearly 1,500 preserves covering more than 2.5 million acres across all 50 states. These lands protect wildlife and natural systems, serve as living laboratories for innovative science and connect people to the natural world.

See the Complete Map

Make a Difference in Hawai‘i

The Nature Conservancy works with people like you to protect Hawai'i’s spectacular diversity of life. Together, we can protect the plants and animals that share our world and support our well-being. We invite you to join the effort.