The Green Heart Louisville Project

This groundbreaking study shows the power of adding trees to a neighborhood as a public health strategy.

In the fall of 2017, The Nature Conservancy, the University of Louisville's Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute, and other partners launched the Green Heart Louisville Project to examine the link between neighborhood greening and human health. Though previous research found an association between nature and well-being, the Green Heart Louisville Project is the first to measure how a "greening intervention" can improve human health.

A First-of-Its-Kind Project

Aruni Bhatnagar, Ph.D., the project's principal investigator and director of the Envirome Institute, worked for more than two years to develop the project idea and build a team around the study.

In addition to The Nature Conservancy, Dr. Bhatnagar recruited Washington University in St. Louis, Hyphae Design Laboratory, Cornell University, the U.S. Forest Service and other researchers and academics to join the project team and contribute their expertise.

At the time, Bhatnagar said no one knew whether and to what extent neighborhood greenery affected human health and why. The Green Heart Louisville Project could help inform how to design a neighborhood that supports human health.

Quote: David Phemister

The project brings together the expertise of university researchers, nonprofit leaders, community organizations, and volunteers to quantify a link between nature and human health. We intrinsically understand the link, but can we prove it?

The Green Heart Project received affirmation and critical support—just one year after project launch—from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to support the clinical trial portion of the project. With a lead grant from the Owsley Brown II Family Foundation, The Nature Conservancy ultimately raised and provided over $8.7 million for tree planting and maintenance, project management and other key project needs. Additional local donors provided another $3 million.

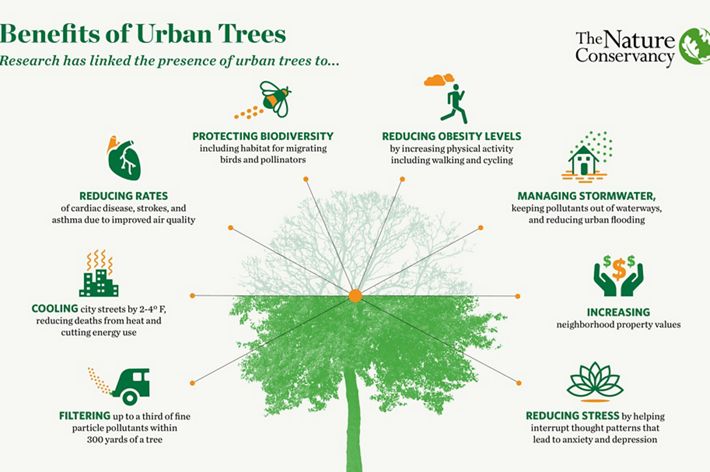

The growing support for the project was rooted in people wanting to invest at the intersection of nature and human health and to build on a growing body of research highlighting a link between urban greening and health outcomes.

However, the Green Heart Louisville Project is the first longitudinal clinical trial to test urban greening in the same way a new pharmaceutical intervention would be tested. Specifically, the research team assessed whether a significant increase in trees and shrubs would contribute to better heart health and other health outcomes.

The Study: Do City Trees Affect Human Health?

To establish the baseline data for the study, the team documented health data from 745 participants, as well as detailed measurements of tree coverage and levels of air pollution, in targeted South Louisville neighborhoods.

Next, the team planted thousands of trees and shrubs throughout the target neighborhoods to create an urban ecosystem that promotes physical activity while decreasing noise, stress, and air pollution. After that, the participants received annual check-ups to evaluate how the increased greenery has affected their physical and mental health, and their social ties.

“The project brings together the expertise of university researchers, nonprofit leaders, community organizations, and volunteers to quantify a link between nature and human health,” says David Phemister, The Nature Conservancy’s Kentucky state director. “New evidence revealed through the study can inform better policies and investments in nature as critical infrastructure and as a viable public health strategy.”

Planting Begins

In October of 2019, The Nature Conservancy and Louisville Grows, a local nonprofit that specializes in planting trees on private property, began planting trees and shrubs in the Green Heart Louisville Project study area. The partners went door-to-door, talking with South Louisville residents about the project and asking if they would be willing to allow trees on their properties.

“In the beginning, the project was really unknown,” says Chris Chandler, cities and strategic partnerships director, Global Equitable Conservation team for The Nature Conservancy. “The first pass through a portion of the neighborhood, we had 10% of residents say yes. That rate of uptake is pretty standard in Louisville, according to our community partners.”

Once the first planting took place, TNC and Louisville Grows knocked on all the doors again and got 15% more residents to say yes. Word was spreading about the project, and residents saw their neighbors receiving trees and wanted to take part.

“Once the community saw that we were making good on what we were talking about, that these weren’t empty promises, we had people say, ‘Hey, my neighbor got that beautiful tree last fall, can I get one?’” says Chandler. “Now they’re starting to see tangible outcomes.”

The Power of Trees for Public Health

Support for the Green Heart Louisville Project was rooted in people wanting to invest at the intersection of nature and human health and to build on a growing body of research highlighting a link between urban greening and health outcomes. Photos © Mike Wilkinson.

Support our work in Kentucky

Transporting Soil: Soil is loaded into a truck for placement in the Green Heart Louisville Project's planting areas on a Louisville highway. © Mike Wilkinson

Applying Soil: Soil is applied to a planting area for the Green Heart Louisville Project as cities and strategic partnerships director Chris Chandler (left) looks on. © Mike Wilkinson

Applying Soil: Trees planted along the Watterson Expressway in Louisville will form a wall that will filter air before it reaches the community. © Mike Wilkinson

Green Heart Planting: Trees as tall as 24 feet are brought in on a semi-truck for planting along a Louisville highway for the Green Heart Louisville project. © Mike Wilkinson

Green Heart Planting: Workers dig holes for installation of large trees along a Louisville highway. The trees will form a wall to reduce air pollution before it enters the community. © Mike Wilkinson

Green Heart Planting: Workers get trees ready to plant along a highway in Louisville. The trees will create a barrier for air pollution to protect the community. © Mike Wilkinson

Green Heart Planting: Workers plant a tree next to the sound wall on a Louisville highway. The large trees will help filter out air pollution from the roadway before it reaches the community. © Mike Wilkinson

Waterson Expressway Planting: Hundreds of trees were planted near and along the Waterson Expressway in Louisville. © Wilkinson Visual

Tree Installation: By planting thousands of trees of varying sizes in Louisville communities, the Green Heart Louisville Project was able to measure how greening effects a community. © Wilkinson Visual

Waterson Expressway Planting : Workers installed hundreds of trees along the Waterson Expressway and the affects were measured in the community. © Wilkinson Visual

COVID-19 slowed down planting activity in the spring of 2020, but trees continued to go in the ground. Ultimately, The Nature Conservancy, Louisville Grows, and a number of private contractors planted over 8,000 trees, including hundreds of trees along the Waterson Expressway, a large highway that bisects the Green Heart neighborhoods. These plantings are designed to create a living wall to filter air from the roadway before it reaches the community. Within the community, thousands of medium-sized trees up to 15 feet tall were planted on private property.

“When we plant trees on private properties, a part of the agreement with the landowners is that they will take care of the trees,” Chandler says. “We educate them, we give them information and pamphlets, and we talk about the cycle of watering.”

Louisville Grows regularly checked on the trees, making sure they were watered and offering supplemental watering if needed. Thanks to a capacity-building grant from TNC, the partner had a 1,000-gallon watering tank to provide additional water as they drove through the neighborhoods.

“The most important thing is that these trees not only survive but thrive, and to thrive we need all hands on deck,” says Chandler. “That’s how the landowner makes an investment in the project, in the care of the trees. The Nature Conservancy and our partners at the Envirome Institute are here to support the community to keep these trees alive.”

Celebrating Hope for a Greener, Healthier Future

In August 2024, after years of caring for the trees and monitoring results, the partners announced the study’s groundbreaking findings.

Researchers at the University of Louisville's Envirome Institute found that people living in the neighborhoods where the project conducted its “greening intervention” showed lower levels of a blood marker of inflammation strongly associated with cardiovascular health, as well as diabetes and some cancers. (Source: UofL news.) This finding is significant, because it means that adding trees to a neighborhood may reduce community members’ risk of heart disease. The Green Heart Louisville Project is the first study to show that an intentional increase in trees and shrubs in a neighborhood can indeed improve human health.

“Most of us intuitively understand that nature is good for our health. But scientific research testing, verifying, and evaluating this connection is rare,” said Katharine Hayhoe, chief scientist of The Nature Conservancy. “These recent findings from the Green Heart Project build the scientific case for the powerful connections between the health of our planet and the health of all of us.”

Thanks to the Green Heart Louisville Project, cities beyond Louisville and across the world have groundbreaking research to guide their efforts to create healthier communities. Investing in trees is an investment in human health–while also making our cities a cooler, more beautiful, and more enjoyable place to live.

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Projects like Green Heart Louisville are made possible through your support. By supporting our work, you can help ensure a future in which nature and people can thrive.

Kentucky Nature News

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from TNC in Kentucky. Learn more about important conservation news near you.