Habitat Strike Teams

Combating invasive species and restoring Missouri’s vulnerable landscapes.

What Are Habitat Strike Teams?

The four-person teams, each comprising a full-time coordinator and three seasonal crew members, are mobile units designed to combat invasive species and help restore vulnerable landscapes.

TNC is staging the teams in different parts of the state. Members are skilled in using prescribed fire and other methods to fight unwanted shrubs, trees and other plants that can overwhelm native habitats.

The teams work on projects on their own, but they’re designed to be highly collaborative with government agencies, conservation groups and private landowners. They add much-needed capacity, especially during time-sensitive burn windows.

Funding for these teams is also a collaborative effort. The Western and Eastern Ozarks teams are funded in part by U.S. Forest Service Cohesive Strategy grants for wildfire risk reduction (Western Ozarks) and cross-boundary work (both teams). The Western Ozarks team is also supported by a Mark Twain National Forest Agreement between TNC and the U.S. Forest Service.

The Osage Plains and Grand River Grasslands teams received support in November 2023 when a group of partners, including TNC, were awarded an America the Beautiful Challenge Grant, which was administered by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. That grant and support from partners like the Missouri Department of Conservation are what make impactful programs like the Habitat Strike Teams possible.

Habitat Strike Team Regions

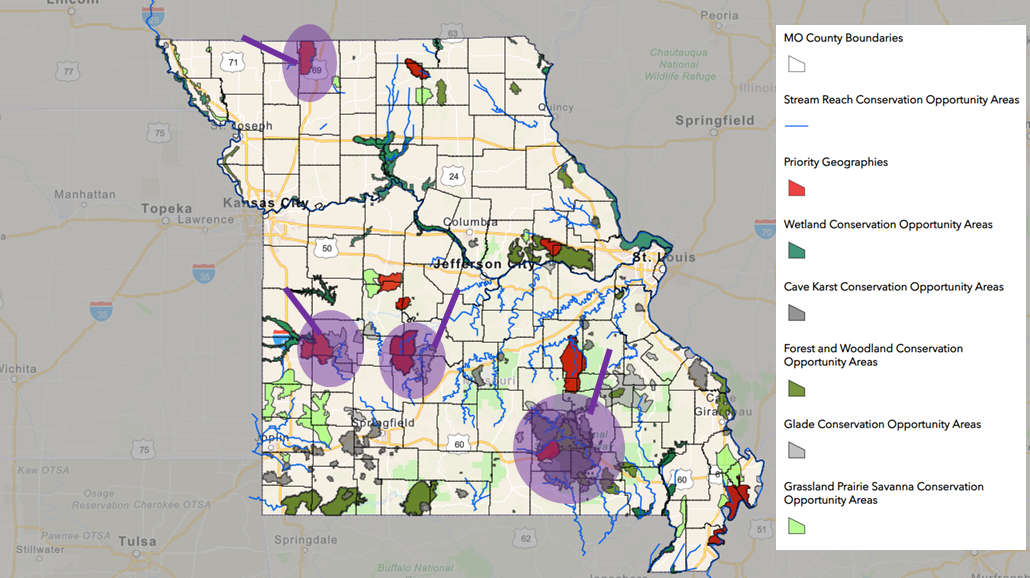

TNC has four Habitat Strike Teams in Missouri. The circles indicate where the teams assist with habitat management on private land. The teams expand beyond these ranges to assist conservation partners who are working on priority landscapes.

Map of Missouri’s Priority Geographies and Conservation Opportunity Areas collaboratively developed and maintained by the Missouri Department of Conservation.

Eastern Ozarks

The Eastern Ozarks region is home to numerous species found nowhere else on earth. This region is known for its many caves, springs and sinkholes, winding rivers and lush woodlands. TNC’s Habitat Strike Team collaborates with landowners and partners including the U.S. Forest Service to implement conservation measures that safeguard this critical habitat.

Primary habitat work: Woodland and glade management on public and private lands, using prescribed fire, timber understory treatments and invasive species treatments.

Species of concern:

Indiana bat

Hine’s emerald dragonfly

Ozark hellbender

Western Ozarks

The Western Ozarks region encompasses rolling hills, dense forests and clear streams and is known for its karst topography, featuring caves, sinkholes and underground rivers. TNC’s Habitat Strike Team works with private landowners and agencies to implement prescribed fire and treatments to keep invasive species at bay.

Primary Habitat Work: Woodland and glade management on public and private lands, using prescribed fire, timber understory treatments and invasive species treatments.

Species of concern:

Eastern hellbender

Bachman’s sparrow

Niangua darter

Osage Plains

The Osage Plains, located in the west-central part of Missouri, encompasses some of the most diverse native tallgrass prairies in the state and is extremely threatened by invasive species. TNC’s Habitat Strike Team works with private landowners and agencies to increase biodiversity supporting the plants and wildlife in the landscape.

Primary habitat work: Prairie management on public and private lands, using prescribed fire, invasive treatments, woody vegetation management and native seed harvest/planting.

Species of concern:

American burying beetle

Mead’s milkweed

Greater prairie-chicken

Grand River Grasslands

The Grand River Grasslands, spanning over 160,000 acres in Missouri and Iowa, is a critically endangered habitat. TNC's Habitat Strike Team collaborates with private landowners to focus on sustainable practices benefiting healthy prairies and working lands. They also collaborate with Drake University for grassland research and workforce development.

Primary Habitat Work: Prairie management on public and private lands, using prescribed fire, invasive treatments, woody vegetation management and native seed harvest/planting.

Species of concern:

Topeka shiner

Mead’s milkweed

Greater prairie-chicken

Battling for Biodiversity

If you were to observe Wah’Kon-Tah Prairie from the air, you would see a struggle for the landscape’s future playing out as a battle of colors.

The wildflowers’ lavenders, whites and yellows dot a front of native grasses, which grade from pale green to gold in the heat of midsummer. Together, they fight to hold ground against creeping, monochromatic green islands of unwanted shrubs and trees—sumacs, persimmons, cherries and oaks—that threaten to turn this open expanse of western Missouri plains into scrubby forests, thick with rush, through a process called succession.

“The No. 1 reason to stop that process is biodiversity,” says Isaiah Tanner, The Nature Conservancy’s Osage Plains fire and stewardship coordinator in Missouri. “That’s mission No. 1.”

There are more than 300 species of plants at Wah’Kon-Tah, not to mention all the wildlife that depends on them. That kind of variety used to be the norm when wild spaces covered the land. Now, it is rare. Less than 4% of the world’s tallgrass prairie remains, making it one of Earth’s most endangered ecosystems. And it’s not just prairies that are in trouble. Ecosystems around the globe are struggling amid twin crises of a changing climate and rapid decline of biodiversity. More than a million species could face the threat of extinction in the coming years, and habitats are disappearing at alarming rates.

Wah’Kon-Tah stands out in that context as a jewel of biodiversity. The land within its boundaries is protected from threats such as development, and it will stay that way. Even so, the habitat needs help. Natural allies of the grasslands, such as bison and elk, were driven from the land by European settlement and federal policies that sought to displace Indigenous tribes. The cascading effects of losing key pieces of the ecosystem have left an opening for invaders.

“One of the reasons we have to fight these shrubs so hard is there are no more elk and no more bison,” Tanner says. “We’re just sort of a proxy.”

Tanner is part of The Nature Conservancy’s strategy to use newly created Habitat Strike Teams in Missouri to combat invasive species and promote biodiversity. Four mobile teams have been staged in priority geographies: Western Ozarks, Eastern Ozarks, Osage Plains and the Grand River Grasslands.

Habitat Strike Teams are designed to be agile and highly collaborative. Members might start a week hacking down invasives on a TNC preserve and finish it by plugging into a multi-agency burn crew, adding the extra hands needed to conduct prescribed fires around the state.

Prescribed Fire

Landscapes across North America evolved with regular fires, both sparked naturally by lightning and set by Indigenous people who developed controlled burning techniques over thousands of years. But a century’s worth of federal policies that sought to exclude fire from the land allowed fuels to pile up and unwanted species of plants to gobble up habitats at the expense of native plants.

Quote: Ryan Gauger

In this landscape, high-quality habitat management and wildfire risk reduction are one and the same.

Restoring balance to those ecosystems can reduce the risk of harmful fires and act as a conservation tool, regenerating natural systems.

“In this landscape, high-quality habitat management and wildfire risk reduction are one and the same,” says Ryan Gauger, who serves as TNC’s fire and stewardship manager in Missouri and supervises the Habitat Strike Teams.

Prescribed fire is one of the predominant tools the strike teams use to open forests and stop the succession process that can turn prairies into savannas and savannas into dense, unhealthy forests if shrubs and trees are left unchecked.

Prescribed fire is just one tool in the toolbox of land managers. During those weeks and months when prescribed fire is either not available or not recommended, the Habitat Strike Teams turn to other methods—everything from hand tools to heavy machinery—and carefully targeted herbicide spraying to beat back unwanted species. Given the typically narrow windows for burning, that is where a large part of the battle against invasives is fought.

Battling Invasives

Outside of fire season, Tanner spends much of his time working back and forth across grasslands, battling invasives. On a broiling day in mid-July, he heads out along a two-track dirt road. The temperature has already hit 98 degrees by midday, and a cell phone weather app helpfully points out that the humidity makes it feel more like 104. Tanner passes buried buckets where visiting researchers created temporary homes for the American burying beetles being reintroduced to the prairie. A pair of quail race out in front of his UTV, an apparent attempt to lure this perceived threat away from a nest hidden in the grass.

The height of wildflower season has passed, but there are still the sunny coronas of compass plants, delicate purple bundles of Missouri ironweed and the odd stalk of cream false indigo that still has a few white petals attached.

“It kind of looks like it’s sticking its tongue out at you,” Tanner says, pausing to gently lift one of the little legume’s flowers with his fingers.

Riding through the prairie here is a reminder of both the challenge and importance of managing such a diverse habitat. The pollinators flitting from flower to flower, raptors soaring overhead and an occasional deer spotted in the grasses are only a hint of the amount of life packed into every square meter. Tanner has settled into a summer rhythm: In the mornings when it’s cooler, he spot-sprays individual stems of Lespedeza cuneata (also known as Sericea lespedeza), an exotic variety of bushclover that wreaks havoc on natural habitats. During the blazing afternoons, he usually switches to the air-conditioned cab of a skid steer outfitted with a mowing deck to blitz stands of unwanted saplings.

The Habitat Strike Teams plan to ramp up with two or three seasonal employees each during fire season. But full-timers Tanner and his counterparts in the Western and Eastern Ozarks each serve as teams of one in the months in between. At Wah’Kon-Tah, he uses a GPS map on his phone to track his progress spraying and mowing. A series of squiggly lines shows where he has been. The zoomed-out view of the map can hide the on-the-ground work that goes into each of those lines. As if to prove the point, a fieldstone hidden in a dense cluster of sumac and wild plum trees bangs up one of the skid steer’s wheels, cutting short the afternoon’s mowing while Tanner figures out how to repair or replace it.

Quote: Isaiah Tanner

Wow, look at that! That really wants to be forest.

Similarly, a storm the next morning proves too breezy for spraying. Higher winds make it too difficult to spray the Lespedeza cuneata without wafting the spray onto neighboring natives, and protecting those is just as important as removing the unwanted ones. Tanner takes advantage of the rare bit of downtime to scout out a few of Wah’Kon-Tah’s far-flung units as prep for future prescribed fires.

He passes units burned within the past seven to eight months that have returned, bursting with flowers and thigh-high grasses. Another, located at a distant corner of the sprawling preserve, shows signs of succession on the rise. Rounding a bend, Tanner spies a swath of young oaks, ranging from saplings standing roughly two feet tall to juveniles cresting eight feet.

“Wow, look at that!” he says. “That really wants to be forest.”

If allowed to take over, the trees would quickly overwhelm the nearby grasses, erasing badly needed habitat for hundreds of prairie-dwelling species. To preserve biodiversity, it’s important that the grasslands stay grasslands, especially with so few remaining.

Crossing the road between the units, Tanner pauses at a gate, where he spots a hopeful sight. Vines of American bittersweet curl around an old wooden fence post, their yellow berries adorning the entrance in a cheerful welcome. Their exotic cousins, known as Oriental bittersweet, have become a noxious weed in the Midwest—a harmful invasive that Tanner had grown intimately familiar with in a previous conservation job. The exotic bittersweet has become so common that it is a surprise to find the native species.

Tanner pauses to appreciate this unexpected sighting before driving on.

“I’m really kind of buzzing about that American bittersweet,” he says after a while. “I can’t tell you how many Oriental bittersweets I’ve killed in Southern Illinois. They’re almost like kudzu, like this apocalyptic plant. So, to see an American bittersweet, just one, is kind of nice.”

Want to Learn More About Our Work in Missouri?

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Missouri. Get a preview of Missouri’s Nature News email.