Going Underground: Protecting the Interior Highlands

TNC is crossing borders to protect our caves and increase water quality.

On maps of the surface, solid lines define the states, separating Missouri from Arkansas, Arkansas from Oklahoma. But in the dark and twisting tunnels of the world underground, those lines don’t mean much.

Thousands of caves, sinkholes and springs cut through the limestone and dolomite that undergird landscapes across our region. And while they hold huge importance for people, as well as an array of species scientists are still discovering, they have little respect for state boundaries. So, The Nature Conservancy is taking a different approach to protect these systems and the unique species that depend on them.

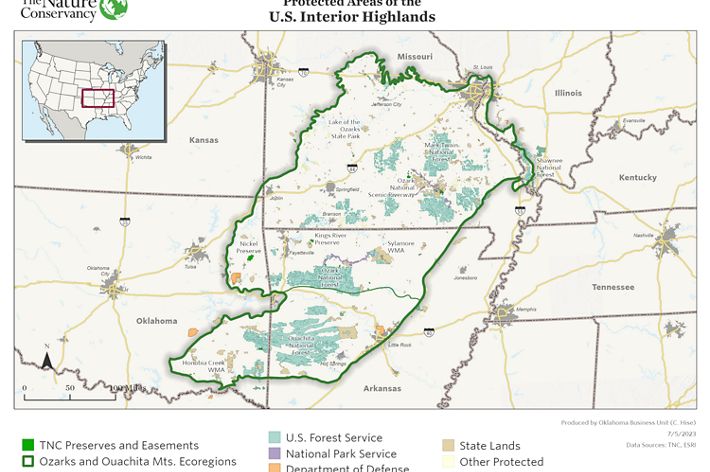

A team of TNC staffers from three states focuses on the Interior Highlands, a region that spans much of Missouri. It runs southwest from the St. Louis metro through the Ozarks and into the northwest corner of Arkansas and the eastern edge of Oklahoma, nicking the corner of Kansas.

Along with caves, the Interior Highlands are home to the unique geology of the Ozarks plateau and the Ouachita and Boston Mountains of Arkansas and Oklahoma. Glades, fens, oak-hickory savannas, prairies and pine forests can all be found within its expanse.

“The Interior Highlands are a fascinating region that includes some of the most biodiverse landscapes on Earth,” says Katie Gillies, TNC’s director of conservation in Oklahoma. “Working across state borders allows us to address it as a whole and figure out where we can make the biggest difference.”

Quote: Mike Slay

We always talk about going to look for unicorns, because of the rarity of some of these species and the off chance you might see them.

Setting Priorities

The TNC team has set two main priorities for the region: reconnecting aquatic habitats by removing barriers that block rivers and streams, and protecting karst systems across the region. Karst systems are the Swiss cheese-like networks of subterranean passageways, popping through the surface as cavemouths, sinkholes and springs. They are formed by mildly acidic water that slowly eats away the rock, creating voids as the water sinks farther underground. Missouri alone has more than 7,000 caves, earning it the nickname “The Cave State.”

Podcast Episode: Cave Talk with Mike Slay

Listen in on a podcast episode to dive deeper into our Ozark Caves.

Start StreamingTNC’s Ozark Karst Project Manager Mike Slay has conducted assessments of karst systems in Arkansas, Oklahoma and Missouri to determine the most vulnerable locations. The work will help protect species we know and, almost certainly, many we don’t. Slay has discovered numerous previously unknown species during his career. Each trip underground has the potential to reveal something new.

“We always talk about going to look for unicorns, because of the rarity of some of these species and the off chance you might see them,” Slay says.

TNC’s Interior Highlands uses the data from Slay’s research to overlay areas of high biodiversity with those of high risk to map karst priorities in the region. Team members then use those priority areas to figure out where to focus resources for the greatest impact.

Starting at the Top

Often, the solutions to the problems facing karst systems start at the top. Sources of food and water enter the karst system from the surface, falling into caves or following the downward flow of water as it sinks farther and farther into the earth. That’s important for species that depend on water and nutrition from above. However, pollutants travel the same flow underground. The porous nature of the landscape can offer direct access for storm runoff and harmful substances that plunge into sinkholes, springs and other natural features.

Curbing erosion and reducing runoff can help keep harmful chemicals from entering caves and underground waterways. Preventing harmful materials from coming in is a lot easier than trying to pull them out later. If you don’t protect your karst system, you could harm a really biodiverse system—and your drinking water supply.

Sign up for Nature News

Get conservation stories, news and local opportunities from where you live.