Protecting and Restoring Missouri's Waterways

The ripple effect of water conservation.

Missouri's rivers and streams are a marvel of nature, offering a glimpse into the intricate workings of our planet's freshwater systems. The confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers forms a river system that is not only the fourth-longest in the world but also drains over a third of the continental United States.

Since 1956, The Nature Conservancy has been at the forefront of studying and protecting these waters, recognizing their critical role in maintaining ecological balance. Through scientific research and collaborative conservation efforts, TNC aims to ensure that Missouri's rivers and streams continue to thrive. By understanding the complexities of these freshwater systems, we can develop effective strategies to combat the challenges they face and preserve their functionality and beauty for future generations.

Explore Our Work in Water

Protecting the Meramec River

A collaborative effort is underway to protect Missouri's Meramec River, ensuring clean water, rich biodiversity and recreational opportunities.

Improving Water Quality

From our rural agricultural fields to our urban cities, TNC is collaborating with partners and communities to protect and improve Missouri's water.

Little Creek Conservation

From stream restoration to sustainable agriculture, a Missouri conservation initiative demonstrates how watersheds can recover.

Mapping the Mississippi

Explore maps that illustrate the Mississippi River's reach, our efforts to control it and the impacts from its flooding.

Sustainable Rivers Program

For much of the 20th century, the United States built thousands of large dams and other water projects to meet the nation’s growing need for water, food, flood risk reduction, hydropower and navigation. But since their construction, the operations of very few public dams have been fully reviewed and updated to meet current needs.

In 2002, TNC and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)—the largest water manager in the nation—launched a collaborative effort to find more sustainable ways to manage river infrastructure to optimize benefits for people and nature. Now known as the Sustainable Rivers Program (SRP), this collaboration has grown from eight rivers in 2002 to 44 in 2022, influencing 12,079 miles of U.S. waterways which includes 90 associated reservoirs and dams.

Whether for flood control or energy production, large dams alter the natural flow of a river system and impact species downstream. The SRP establishes a process USACE can use to study the effects of water released from their dams, solicit technical input on the ecological impacts downstream, propose an altered release schedule to accommodate the needs of downstream species and test those proposed release schedules before including them in a revised operation manual for the reservoir.

In Missouri, TNC has partnered with USACE on the Osage River near Kansas City and the Black River in the southeastern part of the state. The Osage River in Missouri begins as the Marais Des Cygnes in Kansas before crossing the state line, joining the Little Osage River and flowing through Truman Lake on its way to join the Missouri River. Stockton Lake and Pomme De Terre Lake also flow into the Osage River system.

The Black River rises out of the St. Francois mountains in eastern Missouri before it hits Clearwater Lake upstream of Poplar Bluff, and then flows into Arkansas, where it joins the White River and eventually the Mississippi.

Removing Barriers: Clearing the way for free-flowing rivers

Dams, low-water road crossings and some culvert bridges pose a significant barrier to the movement of fish, cost a lot to maintain and can be a hazard for people during high-water events.

In an effort to connect stream miles and address the other concerns, TNC has been working with wildlife agencies, local governments and road districts to replace barriers with free-span bridges and other solutions that allow free movement of wildlife.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently awarded nearly $1.5 million to Crawford County for the replacement of two crossings in Huzzah Creek. TNC helped prioritize these two projects for the state and worked with partners to make the application competitive. This is the first fish passage project in Missouri funded by the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and it will open 25 miles of river, building on past replacements at Bricky Slab and Willhite Road, also located in Crawford County.

The Missouri Aquatic Connectivity Team, which is co-led by the Missouri Department of Conservation and TNC, is working to make in-stream barrier removal and bridge replacement easier, more affordable and more widely accepted as the best practice in managing streams across the state.

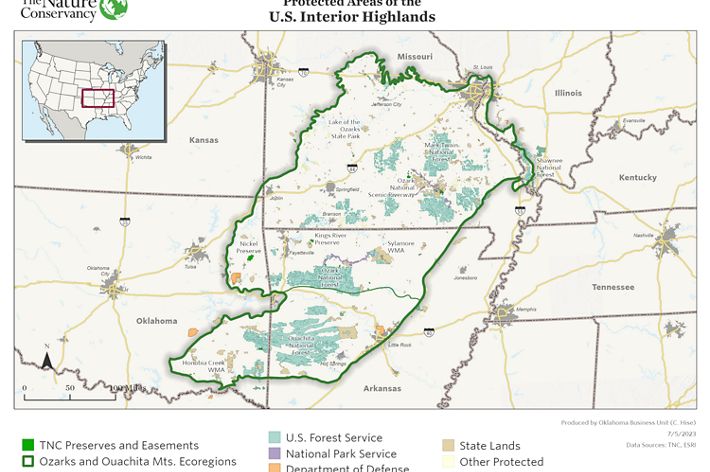

Interior Highlands

The Interior Highlands is a region that spans much of Missouri, running southwest from the St. Louis metro through the Ozarks and into the northwest corner of Arkansas and the eastern edge of Oklahoma, nicking the corner of Kansas.

Thousands of caves, sinkholes and springs cut through the limestone and dolomite that undergird this landscape, holding huge importance for people, as well as an array of species scientists are still discovering.

Along with caves, the Interior Highlands are home to the unique geology of the Ozarks plateau and the Ouachita and Boston Mountains of Arkansas and Oklahoma. Glades, fens, oak-hickory savannahs, prairies and pine forests can all be found within its expanse.

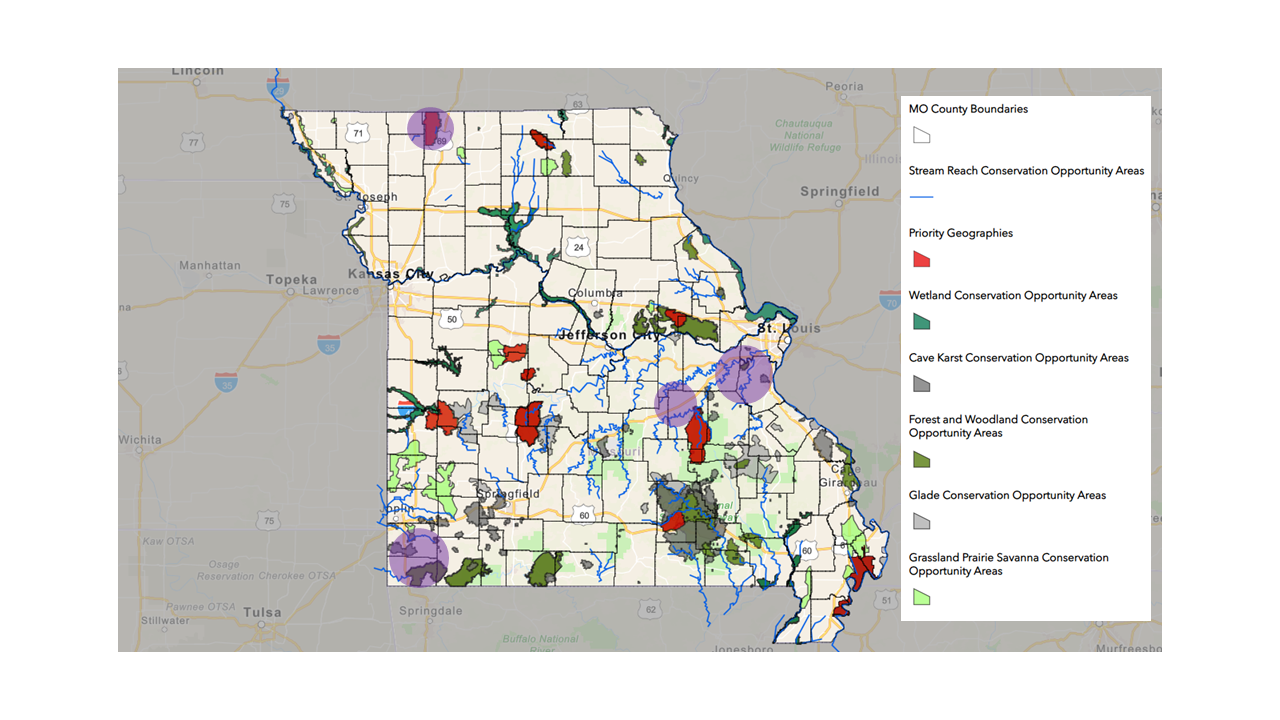

TNC is focused on two main priorities for the region: reconnecting aquatic habitats by removing barriers that block rivers and streams and protecting karst/cave systems across the region.

The Interior Highlands team will use the data from recent TNC research to overlay areas of high biodiversity with those of high risk to map karst priorities in the region.

Once they have those priority areas, team members can figure out where to focus resources for the greatest impact.

Often, the solutions to the problems facing karst systems start at the top. Sources of food and water enter the karst system from the surface, falling into caves or following the downward flow of water as it sinks farther and farther into the earth. That’s important for those species that depend on food and water from above.

However, pollutants travel the same pathways to reach the underground. The porous nature of the landscape can offer direct access for storm runoff and excess nutrients that plunge into sinkholes, springs and other natural features.

Curbing erosion and reducing runoff can help keep harmful chemicals from entering caves and underground waterways. Preventing harmful materials from coming in is a lot easier than trying to pull them out.

4R Nutrient Management Program

All land uses and practices impact water quality. Depending on the use and practice, this could benefit or harm nearby rivers and streams. That’s why many of TNC’s water strategies focus on what’s happening on the land. Such is the case with the 4R Nutrient Management Program.

When the 4R program was launched in Missouri in 2018, it brought together a diverse group of partners, including the Missouri Fertilizer Control Board, Missouri Agribusiness Association, Missouri Corn Merchandising Council, Missouri Soybean Merchandising Council and TNC.

The 4Rs refer to using the right fertilizer source at the right rate at the right time in the right place. Putting them together simplifies nutrient (fertilizer) management and practices to improve soil health and limit harmful runoff in our rivers and streams.

The 4R program works with farmers and their advisors as they strive to achieve productive, economic, and environmental goals using an approach focused on sustainability. Fertilizers are important for growing food, but figuring out when, where and how much to use can force farmers into a guessing game.

As a result, a significant amount of fertilizer is washed away by rain, leaving the fields and entering nearby rivers and streams. This causes issues for fish, recreational activities and drinking water—and it wastes money. 4R helps farmers create science-backed plans, tailored to their fields.

The partnership hit a big milestone in early 2024 when it reached more than 400,000 acres certified under the 4R program in Missouri. Additionally, the 4R program was selected as one of eight incentive programs under the Missouri Climate-Resilient Crop and Livestock Project. The project helps Missouri producers create more resilient crop and livestock systems by providing incentive payments for a wide range of climate-smart practices.

Podcast: Moving a Levee on the Missouri River

Listen in on a podcast episode to dive deeper into the L-536 Project.

Start StreamingMissouri River Levee Setback Project

People in Atchison County know the Missouri River. They know floods, too. So in 2019, when longtime residents saw surging waters pummel the levee system like never before, they understood better than anyone that something had to change. TNC helped them do it.

We convened partners from across the state with Atchison County Levee District No. 1 and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to figure out a plan. With the district and residents in the lead, the group had an ambitious goal: moving five miles of levee inland to reconnect 1,040 acres of floodplain.

The construction of a levee setback

The project was complex, but it was supported by the buy-in of local landowners, who knew what was at stake. Three of the six highest river crests recorded since the levees were built more than 70 years ago had occurred in the past decade.

The 2019 crest topped the Great Flood of 1993 by more than a foot. Some 56,000 acres were underwater in 2019, and an estimated $25 million of agricultural revenues were lost. The levee setback project, which compensated landowners for easements, gave the river room to move without wreaking havoc. It’s now a model for communities facing similar problems.

Following the historic flood, and construction of the levee setback the partner group took their lessons learned and collaborated on the L-536 Levee Setback Playbook—a how-to guide for communities interested in pursuing similar nature-based solutions that enhance flood resiliency.

Stream Restoration Projects

Crumbling banks along Missouri’s streams and rivers destroy fish habitats, overtax water treatment facilities and cost property owners huge chunks of land. Over the past 10 years, TNC has partnered on major stream restoration projects throughout the state. These projects serve as demonstrations of how we can use bioengineering processes to rebuild streambanks, stop erosion, increase water quality and create new habitats for fish and other wildlife.

Stream Restoration Projects

Eroding streambanks are among the biggest threats to our rivers and streams, dumping tons of sediment and nutrients into the water that harm people and aquatic communities alike. Traditional solutions include added rocks, or rip-rap, along the banks. But there's another way.

Using bioengineering solutions that stabilize banks with natural materials such as trees and live plantings provides better long-term protection and critical habitat for aquatic species to survive. These techniques are commonly used nationwide but are rarely implemented in Missouri.

We've demonstrated these techniques on stream restoration projects around the state with a host of partners, from private landowners to state and federal agencies, to show how we can work with nature instead of against it.

Kiefer Creek

Running through the heart of Castlewood State Park in St. Louis County is Kiefer Creek—a small but important tributary to the Meramec River, which eventually makes it way to the Mississippi River and all the way down to the Gulf of America.

Here, TNC worked with, the State of Missouri, Missouri Department of Natural Resources and Missouri State Parks to stabilize more than 2,000 feet of severely eroding stream bank and improve approximately nine acres of riparian habitat—which is the vegetation and plant communities surrounding the creek.

LaBarque Creek

LaBarque Creek is the most biologically diverse creek that flows into the Meramec River in the St. Louis area. It’s home to over 40 fish species and runs approximately 6 miles before it reaches the Meramec, just south of Eureka, MO.

In 2016, Washington University’s Tyson Research Center contacted TNC to help restore a 250-foot stretch of an extremely eroding streambank on a tight bend of the creek that had dumped over 400 tons of soil and sediment into the creek in previous years. The project was a success and fish monitoring shows an increase in species quantity and diversity.

Huzzah Creek

Huzzah Creek is an ecologically and economically significant drainage in the Meramec River Basin. It hosts a vibrant kayaking and floating industry, providing among best-in-the-state fishing for smallmouth bass. It also supports farmers that rely on its floodplains for livestock grazing and feed crops.

At this site, TNC worked with the Missouri Dept. of Conservation, Ozark Land Trust and a landowner to stabilize nearly 2,000 feet of eroding streambank by implementing bioengineering techniques to stop the erosion, enhance habitat for fish and wildlife and keep private land from washing away.

Elk River

This property on the Elk River lost an astonishing 8,000 tons of soil annually, in total an area of about seven acres in size and ten feet deep.

Working with the Dept. of Natural Resources, the statewide Soil and Water Conservation Program and a private landowner, TNC used bioengineering techniques on 1,600 feet of streambank to stabilize erosion and improve habitat for fish and wildlife, and downstream recreation.

This site is now used to demonstrate to community leaders, private landowners and other stakeholders how about the techniques and how they can be applied elsewhere.

Little Creek

The project at Little Creek had two main goals, stop the erosion that was harming the quality of the creek and fix a perched culvert that was creating a barrier for the Topeka shiner, a federally endangered minnow to migrate up and down the stream for food and breeding.

Now both sides of the creek are re-connected through the culvert using a bioengineered underwater ramp that ensures a more gradual and natural slope. This should allow Topeka shiners and other species to migrate up and downstream to access more habitat.

Most recently, TNC has been working in the Huzzah Creek watershed, an ecologically and economically significant drainage in the Meramec River Basin. Here, TNC is working with farmers and landowners to secure their streambanks and keep their land from washing away.

Similarly, in southwest Missouri, TNC restored 1,650 feet of streambank along the Elk River in McDonald County, where a landowner was losing 8,000 tons of soil to erosion every year.

Beyond the benefits to the individual sites, TNC’s goal is to advance learning about streambank restoration practices throughout the state and beyond, particularly within various cost-share programs, transforming how we manage our streams for people and nature.

Sign up for Nature News

Get conservation stories, news and local opportunities from where you live.