Sharks of New Jersey

Three shark species reproduce in New Jersey’s back bays and coastal marshes. Get to know them—and their bigger counterparts in the Atlantic!

Ocean biodiversity begins with sharks, which are key indicators of an ecosystem’s health; if they are thriving, then the ecosystem is functioning well. Similarly, they are an umbrella species, meaning that efforts to protect them and their habitat has rippling benefits for a spectrum of species, from stingrays and hammerheads to migratory shorebirds, waterfowl and diamondback terrapins. And, because they keep the food chain balanced, sharks also indirectly sustain marine environments like seagrass beds and reefs.

New Jersey’s coastal wetlands and back bays play an important role in the life cycle of several shark species, serving as nurseries and providing growing young with an abundance of resources.

Nature’s Nursery

New Jersey has 200,000 acres of coastal salt marsh. These estuary habitats clean the water and act as a first-line defense against the force of incoming waves for coastal communities. They drive economic benefits through recreation and fishing. And they are a critical nursery for biodiversity, sustaining birds, crabs and fish including...sharks.

Cape May Wetlands: TNC staff surveys results of a marsh restoration project in Avalon, NJ. © George Steinmetz

Blue Crab: Smooth dogfish and sandbar sharks feed on blue crabs. © Erika Nortemann / The Nature Conservancy

Cape May Wetlands: Tall wetland grasses provide growing young shark pups with safe, predator-free habitat. © George Steinmetz

Juvenille Sandbar Sharks: Young sandbar sharks form schools in shallow coastal nursery grounds, moving into deeper warmer waters in winter. © Shutterstock

Calm, shallow salt water bodies like Barnegat Bay and Little Egg Harbor provide ideal conditions for offspring of the smooth dogfish, sandbar shark and sand tiger shark species. Juveniles, called pups, receive no maternal care after their live birth, so will quickly take protective cover among the marsh grasses. The resource-rich wetlands also provide stable and abundant food like crustaceans, fish and rays, improving the shark pups’ odds for survival.

The young sharks will generally remain in the estuary to grow in size, skill and confidence for about a year before swimming out to the open ocean where life is a bit more dangerous. Apex predators like great white and mako sharks lurk in the deep and will not hesitate to make a meal out of their smaller cousins. Juveniles that survive this first foray into the Atlantic often return a few months later to their birth bay to spend a second year maturing. After that, they will spend their lives at sea.

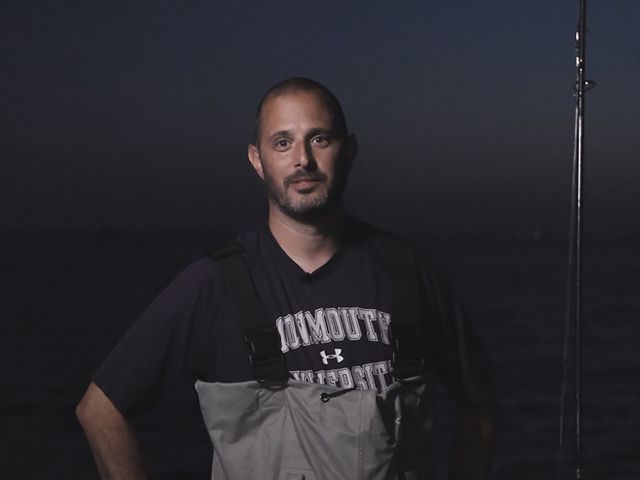

Scientists have been tracking shark movements using technology for years. To learn more about shark tagging and how sharks use New Jersey’s coastal wetlands and back bays, TNC worked on a video with Keith Dunton, Associate Professor of Biology at Monmouth University. Dr. Dunton, a shark specialist engaged in local research, explained that shark tags are small, implanted devices that send out acoustic “pings”. These “pings” are picked up by sensors along the east coast so scientists can monitor the sharks’ journey—kind of like an EZ Pass—allowing scientists like Dr. Dunton to see how sharks are moving through New Jersey’s marshes and along the coast.

Quote: Dr. Keith Dunton

“They give live birth to pups in the bay, which is a calmer habitat rich with food. The juveniles spend about a year feeding and growing here, and then head out to the ocean. Some will come back in their second year.”

The title says: Sharks and Their Coastal Habitats in New Jersey. Under the title is an illustration of a marsh, with sharks swimming in and out of it. Several features of the marsh are highlighted: eelgrass, clam worms, marsh grass shrimp, menhaden, longfin squid, skates, quahogs, and blue crabs. Under each highlighted feature is a description. Dogfish pups eat clam worms and other polychaetes, shrimp, crabs, and small fish. Eelgrass provides cover for young sharks to rest and hide from predators. Marsh grass shrimp are a favorite meal for shark pups. Menhaden are an important food source for sharks at all life stages. Female sharks give birth to live pups which feed and grow in the salt marsh and bay before swimming out to the ocean. More mature sharks will hunt for longfin squid in the ocean. Under this text, there are three images of sharks, a smooth dogfish, a sandbar shark, and a sand tiger shark. Directly under the sharks is a long description which says; smooth dogfish, sandbar sharks and sand tiger sharks use New Jersey's back bays as important nursery areas. Their pups rely on the salt marsh habitat to hide, feed, and grow, often returning their second and third years. The marshes are critical for the life cycle of these species and many others in the biodiversity web. Salt marshes are degrading from accelerating sea level rise, boat wakes, storm waves and hardened shorelines, putting the sharks that rely on them at risk. The Nature Conservancy is working to help restore and maintain New Jersey's more than 200,000 acres of coastal wetlands through innovative natural solutions and advocacy. We are also funding research that will provide insight into what conservation actions are needed regionally to help sharks survive for the future. A small map on the bottom right corner of the infographic shows the sharks' migration routes along the coast of New Jersey. The description says: Smooth dogfish, sandbar sharks and sand tiger shark migration patterns in NJ's Great Bay and Little Egg Harbor.

Restoring Shark Habitat

With more frequent, unpredictable storms and sea level rise accelerating, many of New Jersey’s salt marshes are drowning. If the grassy expanses continue to degrade unchecked, they will no longer provide the nurturing resources and conditions to sustain sharks and many other species.

The Nature Conservancy is using innovative natural solutions to help salt marshes persist. Employing a technique that uses dredged sediment from clogged boat channels to give struggling marshes a boost, TNC and partners have restored 60 acres of marsh in Avalon and Fortescue. With results showing promise, we are promoting expansion of the approach to other sites while advocating for additional policies that protect and restore coastal habitats in New Jersey for people and as a wildlife nursery.

Despite the entertainment industry portraying these undeniably charismatic fish relentlessly as villains, our fear of sharks should be eclipsed by an even more terrifying thought: a world without them.

Stay connected for the latest news from nature.

Get global conservation stories, news and local opportunities near you. Check out a sample Nature News email.

Sharks in New Jersey’s Marshes

New Jersey Shark Species: In the Bays

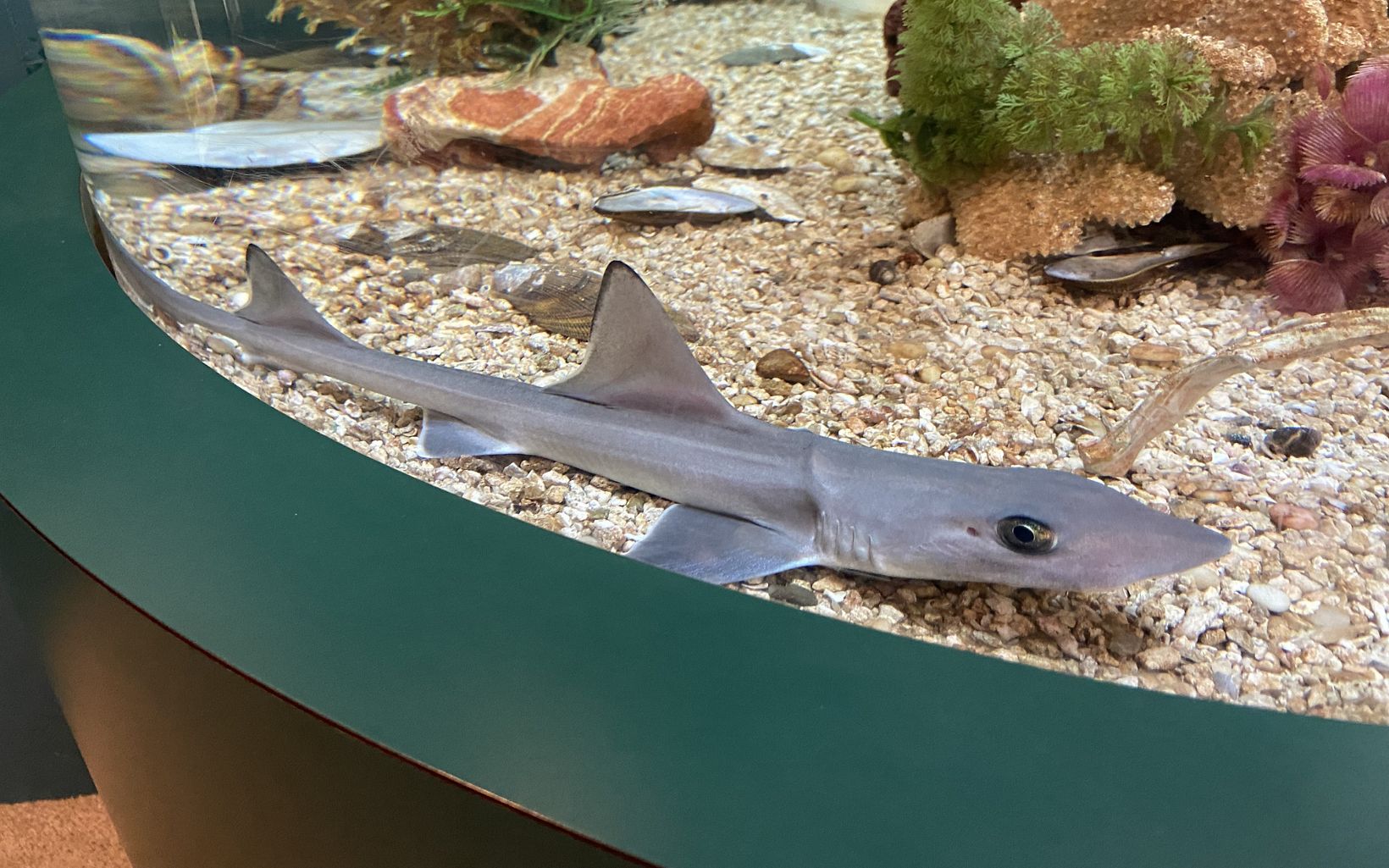

Smooth Dogfish (Mustelus canis)

Description: Small, slender sharks with gray or tan upper bodies and white bellies. On average, they grow up to three feet long.

Habitat: These sharks commonly reside on continental shelves, and in bays and other inshore waters. Smooth dogfish nurseries have been documented in New Jersey’s estuaries and shallow tidal waters, particularly Great Bay and Little Egg Harbor. Some smooth dogfish will live their entire lives in the back bays.

Fun Fact: Smooth dogfish feed on crustaceans, squid, bony fish and small shellfish, using their tiny, rounded teeth to crush prey. They are also a favorite food of sand tiger sharks.

Sandbar Shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus)

Description: Sleek, medium-sized sharks that range in color from gray-brown to bronze with white bellies. Their moderately long, rounded snout contributes to their overall length of up to eight feet.

Habitat: Sandbar sharks prefer bays, harbors and even the mouths of rivers where, true to their name, they frequent shallow waters over sandbars. Barnegat Bay and Delaware Bay are prime nursery areas for this species.

Fun Fact: Sandbar sharks are the most commonly seen toothed shark in New Jersey’s coastal bays.

Sand Tiger Shark (Carcharias taurus)

Description: Large sharks with robust, muscular bodies of light brown or gray color. They can grow to nearly eleven feet and 300 pounds! Sand tiger sharks have distinctive, menacing-looking mouths with large, pointed teeth that visibly protrude even when closed.

Habitat: Habitat for this species includes the surf zone, shallow bays, and coral and rocky reefs. There is evidence that Delaware Bay may be a nursey area for sand tiger sharks.

Fun Fact: Sand tiger sharks burp! For buoyancy while hunting, they gulp air at the water’s surface to inflate their stomach. Sometimes they take in too much air and have to release it.

New Jersey Shark Species: In the Ocean

Atlantic Common Thresher Shark (Alopias vulpinus)

Description: The hallmark of these slender sharks is their long tail (caudal) fins, which measure roughly half the total length of their body. Their bellies are white while the rest of their body ranges from brown, gray, blue-gray to blackish.

Habitat: Inhabiting coastal and deep ocean waters alike, they are familiar fish in New York Harbor and along New Jersey’s coast. Though most commonly observed far from shore, at times they will venture closer in search of food.

Fun Fact: Threshers slap prey with their tail, stunning them long enough to devour.

Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias)

Description: Very large sharks with gray, torpedo shaped bodies and white bellies, a pointy snout and sizeable mouths filled with rows of razor-sharp teeth.

Habitat: Warmer coastal waters in the south are their preference, but they appear regularly along the coast of New Jersey. In 2016 a great white nursery was discovered in the New York Bight, an area along the Atlantic Coast that extends northeasterly from Cape May Inlet in New Jersey to Montauk Point on the eastern tip of Long Island, New York.

Fun Fact: Great white sharks are the largest predatory fish in the world, reaching up to 21 feet long and 4,300 pounds! It is not unusual for tagged great whites—sometimes with amusing names like Mary Lee (who has her own Twitter account), Ironbound and Maple—to “ping” off the coast of New Jersey.

Other Sharks Found in New Jersey