Diagnosing Sick Salt Marshes

Medical technology helps conservationists respond to the climate crisis.

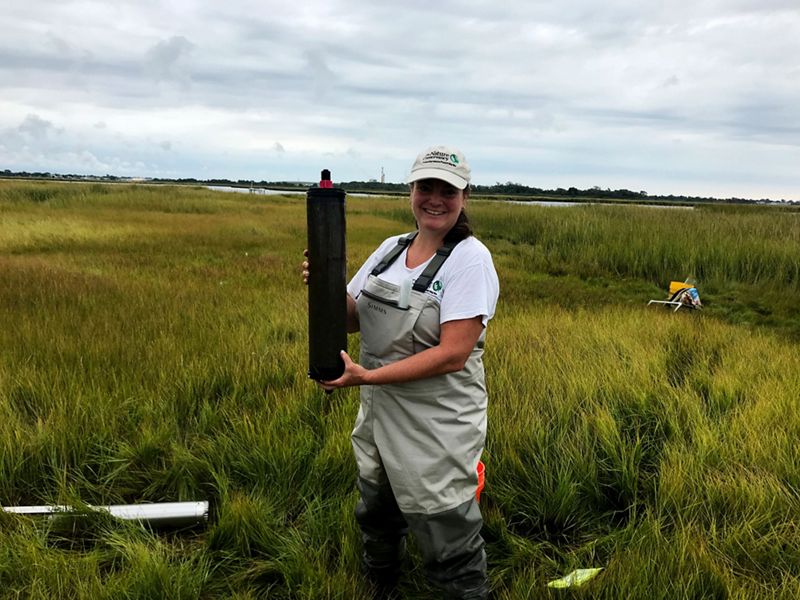

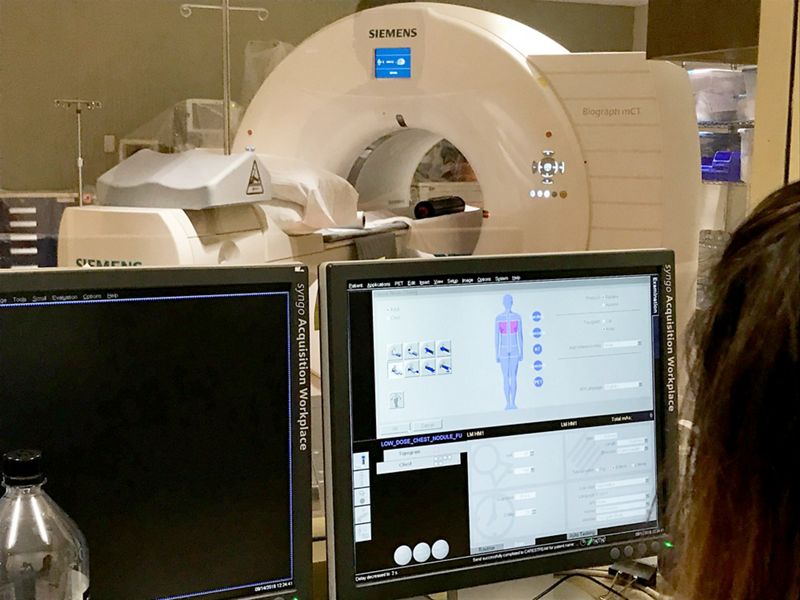

Carmen Arana, a CT technologist at Northwell Health Imaging on Long Island, helps position a patient on the bed of the scanner, lowers the lights and calibrates the machine to the setting used to examine a person’s lungs. But this patient is like none she’s worked with before—it’s a clump of grass, dirt and roots pulled from deep within a salt marsh 15 miles away.

For human patients, a CT (computer-aided tomography) scan provides a closer look at what we can’t see with our eyes, helping doctors detect what’s broken, diagnose an invisible disease or assess a problem before it gets worse. The technology helps determine the best course of treatment and can inform the path to recovery.

Now, The Nature Conservancy’s scientists are using CT technology to do the same for salt marsh ecosystems in New York.

Keeping Coastal Defenders Healthy

Salt marshes play a critical role in filtering water, supporting the coastal food web and absorbing wave energy, but many of these ecosystems on the coast of Long Island are sick. Chronic nitrogen pollution from septic systems and sewers has changed the way the plants grow (above and below ground), which has compromised their ability to resist erosion.

But for years, appearances seemed to tell a different story. A declining salt marsh can look deceptively healthy above ground.

“Because you see taller, greener plants, many people weren’t concerned about pollution harming these marshes,” says Dr. Nicole Maher, The Nature Conservancy’s New York Senior Coastal Scientist. “But under the surface they were becoming flimsy and weak, losing the bulky underground structure they need to thrive.”

Just like when we’re sick and can’t perform as we usually do, it’s the same for marshes. Chronic pollution has left them unable to keep up with our changing climate, especially rising seas. This spells trouble for people, too. Without healthy marshes and wetlands, our water quality deteriorates, and coastal communities are more vulnerable to flooding. The Nature Conservancy team must work quickly to figure out how improving water quality can help Long Island’s salt marshes continue to defend our coasts.

An Inside Look into Underground Roots

CT technology has proven to be a rapid, accurate and high-resolution method for determining salt marsh health. It can do this by peering into the interior lattice of roots, rhizomes, peat and soil particles of sampling cores that scientists take from marsh sites. Interestingly, this underground botanical network resembles the bronchioles in human lungs.

The traditional method of assessing belowground marsh health is a labor-intensive process of cutting thin slices of the sediment core, individually washing them through a series of sieves, picking through materials to sort and examine particles, then reconstructing the core from the individual pieces.

At the imaging facility, Arana and her team can get this information in a matter of minutes.

“The collaboration with Northwell was a game-changer,” says Maher. “At every turn people have been enthusiastic to help.”

The imaging center donated the use of the scanner and technologists’ time. Two preeminent labs at Hofstra University helped prepare and process samples. Research partner Dr. Troy Hill of Florida International University helped process and interpret the data. And Dr. Earl Davey, the retired Environmental Protection Agency scientist who pioneered these novel methods, consulted on the project.

A Living Laboratory

Thanks to prior advocacy by The Nature Conservancy and partners, the team also has access to the perfect living laboratory for studying a key contributor to Long Island’s natural climate solutions.

In Hempstead Bay, Long Island, over $1 billion in Hurricane Sandy recovery funding is being used to upgrade the Bay Park Sewage Treatment plant and send the wastewater out of the enclosed coastal bay into deeper waters, effectively turning off the flow of pollutants that have been compromising this region for decades.

Quote: Carmen Arana

Environmental health is human health. It's exciting to see that our daily work can be used to understand the health of our marshes.

By sampling and analyzing the condition of this site as well as other reference sites, the TNC team will be able to test whether—and on what timeframe—improving water quality can help salt marshes rebound. This work will inform coastal restoration efforts throughout Long Island and beyond.

As she’s leaving the imaging lab, Maher gathers up the core samples and thanks the team for seeing her unique patient. Arana shrugs it off. “Environmental health is human health,” she says. “It’s exciting to see that our daily work can be used to understand the health of our marshes. By learning more about our environment, we can make sure we are doing everything we can to protect it.”