Identifying Fish Species at the Roanoke River

If you have a thing for fish, join us on a sampling day while we prepare for hydrologic restoration.

The Roanoke River is the longest river in North Carolina; it runs through the eastern edge of the Appalachian Mountains to the Piedmont, and it drains into the Albemarle Sound, which eventually connects to the Atlantic Ocean. The river doesn’t follow this long trajectory alone; different kinds of fish inhabit the water. They travel with the flow during the winter and return to floodplains during the summer to spawn.

Dams throughout the river interrupt this natural cycle, which is why TNC partnered with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to create the Sustainable Rivers Program. This program focuses on managing water releases from dams to improve water quality and forest and wildlife health. Dams are not the only barriers that affect aquatic life at the Roanoke River. Fish such as Blue herring and Striped bass spend most of their lives at sea but migrate to their historic spawning grounds to lay their eggs. These spawning grounds are floodplains where the water is warmer and has fewer predators. But what happens when fish can’t get to these floodplains? In past centuries, people altered the floodplains, installing different kinds of barriers, including culverts, which have disconnected the river from its floodplains and impacted fish populations.

Put on your waders; let’s go fish sampling!

Hydrologic restoration is all about returning the water flow to its most natural state, so we are focusing on replacing culverts with fish-friendly bridges. Why are bridges better than culverts? The width of the water stream is always bigger than the culverts, so it narrows down the flow, causing the water to sit at one end and the other.

Fish Traps: TNC NC is restoring the floodplain at the Roanoke River. Fish sampling helps reveal the diversity in the area before and after restoration. © Sophia Torres

Fish-Friendly Bridge: At the Roanoke River, we are replacing undersized culverts with fish-friendly bridges to help fish swim upstream to places they like to spawn. © Sophia Torres

Culverts: At the Roanoke River, we are replacing culverts with fish-friendly bridges so fish can swim upstream to spawn. © Sophia Torres

Fish Sampling Tools: TNC NC is restoring the floodplain at the Roanoke River. By sampling fish, we'll determine the fish diversity in the area before and after restoration. © Aaron McCall

eDNA Sampling: Environmental DNA helps determine the diversity of fish present in an area. © Fauna Creative

This problem gets worse when culverts get filled with debris, which stops the water from going through the culverts, trapping fish that are trying to swim upstream or downstream, which causes them to die. Bridges allow water flow to rise and fall, while fish swim freely up and down the stream and spawn in the floodplains, as they have always done.

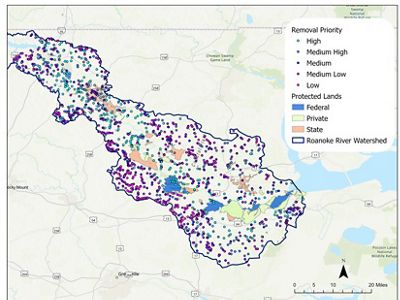

Aaron McCall, TNC NC land steward, is leading this work in collaboration with Chase Spicer, ECU PhD student and TNC fellow. The map below shows the 1,400 barriers identified and ranked according to their removal priority—which is determined by data on historical fish spawning areas and if the barrier sits on conservation lands—so that restoration has the most impact.

eDNA

eDNA testing requires a lot of teamwork. Just a few hours after being collected, the samples are quickly sent to ECU to be filtered because DNA deteriorates fast.

Once the sites have been selected, we conduct an initial diagnosis. We measure environmental parameters such as temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, clarity of the water, depth, and the width of the floodplain. We also take a water sample for eDNA (environmental DNA) testing, which reveals if anadromous fish have been in the water based on the DNA they shed and leave behind. Lastly, we sample fish to estimate the diversity of species using a specific site. We measure above and below the culvert—to determine if there are differences in diversity and if fish are swimming through the culverts. This data allows us to see the results of the restoration work, as well as inform other restoration projects.

Electrofishing

Electrofishing doesn’t harm the fish. The waves put them in a state that constricts their muscles and impedes their ability to swim. As soon as they are put in the oxygen-filled water bucket, they start swimming again like nothing happened, and then they are released into the river once we collect the data needed.

We use two fish sampling methods: backpack electrofishing and fish traps. The water depth at each site is going to determine which sampling method to use. “One day you can have the water depth be at a certain level and use electrofishing, but the next day it can be different, and we have to adjust. We are always competing against water depth,” states Chase Spicer. Backpack electrofishing has been the most effective tool so far, but the water needs to be wadable. On days when the water level is too high, Chase and Aaron set fish traps.

Fish traps

Fish traps come in different sizes to avoid predation in one single trap. They are carefully extracted and handled for the fish’s safety.

During a hot July week, Chase and Aaron spent three days at the river, sampling while cooling off from the heat. They were able to sample six sites. “There is no normal day of sampling,” Aaron laughs. “If we are setting traps, we get them laid out, bait them and place them in their locations. Then we let them soak for 24 hours, and we go back and follow the same sampling protocol as any other sampling method,” says Aaron. This protocol consists of catching the fish, placing them in a bucket with water, recording their data (size, weight, species, picture) and releasing them back into the water. Aaron and Chase work as a team throughout this process. The goal is to be as efficient as possible while making sure that the fish go through the least stress possible. Only one person is in charge of handling them, and the buckets have aerators, so the fish have good quality of water. “When we do backpack shocking, Chase runs the backpack, and we both have deep nets, and it kind of looks like two grown kids walking through a creek and seeing something and trying to catch it in their nets and then putting it in a bucket,” shares Aaron. While expensive, eDNA samples are always taken, and this has been our sampling method of choice because it is more efficient and doesn’t stress the fish.

So far, the study shows that there tends to be more species below the culverts than above them. This population difference indicates that there is a lot of floodplain, creek or swamp area above the culvert that could be used by fish. But fish aren’t moving upriver to lay their eggs.

Tom Barrett, an Environmental Scientist at Ecosystem Planning and Restoration (EPR), has joined this project. Tom and Aaron are working together on assessing the area and designing a plan to reconnect 8,000 feet of stream to the river for fish to spawn.

Tom grew up around the Roanoke River area, almost 50 miles away from the restoration site, so for him, this work is meaningful on a personal level. Electrofishing was on his bucket list of things he always wanted to do, so when Aaron invited him to do fieldwork, he was very excited. “I have fished the river my whole life and hunted there as well, but actually seeing what is in the water through electrofishing was on my bucket list. It’s fascinating because you get to see what’s in the water without harming the fish or pulling them out. We caught a bunch of eels and a couple of fish; it was a great day. When you spend time with people who really enjoy what they are doing, it is always a great day.”

Fish Species Identified at the Roanoke River

This list contains some of the fish species that we have identified during this research.

-

Largemouth Bass

America’s most popular sport fish. They can grow up to 29.5 inches and live for 16 years. Big fish, big appetite! Largemouth bass can eat prey up to 35% of their body length. Males are very protective fathers, guarding their eggs.

-

Pirate Perch

Small fish that can grow up to 5.5 inches and have a unique ability to chemically camouflage themselves from prey. As they grow, their anus travels to their throat, so these fish poop out of their mouths.

-

American Eel

Spends most of its life in fresh water before transforming into silver eels and adventuring to the ocean. A single female eel can lay up to four million eggs.

-

Creek Chubsucker

Is a resident migratory species that can grow up to 15 inches and live up to six years. These fish are bottom-feeders and love cleaning out riverbeds, eating algae and small clams.

-

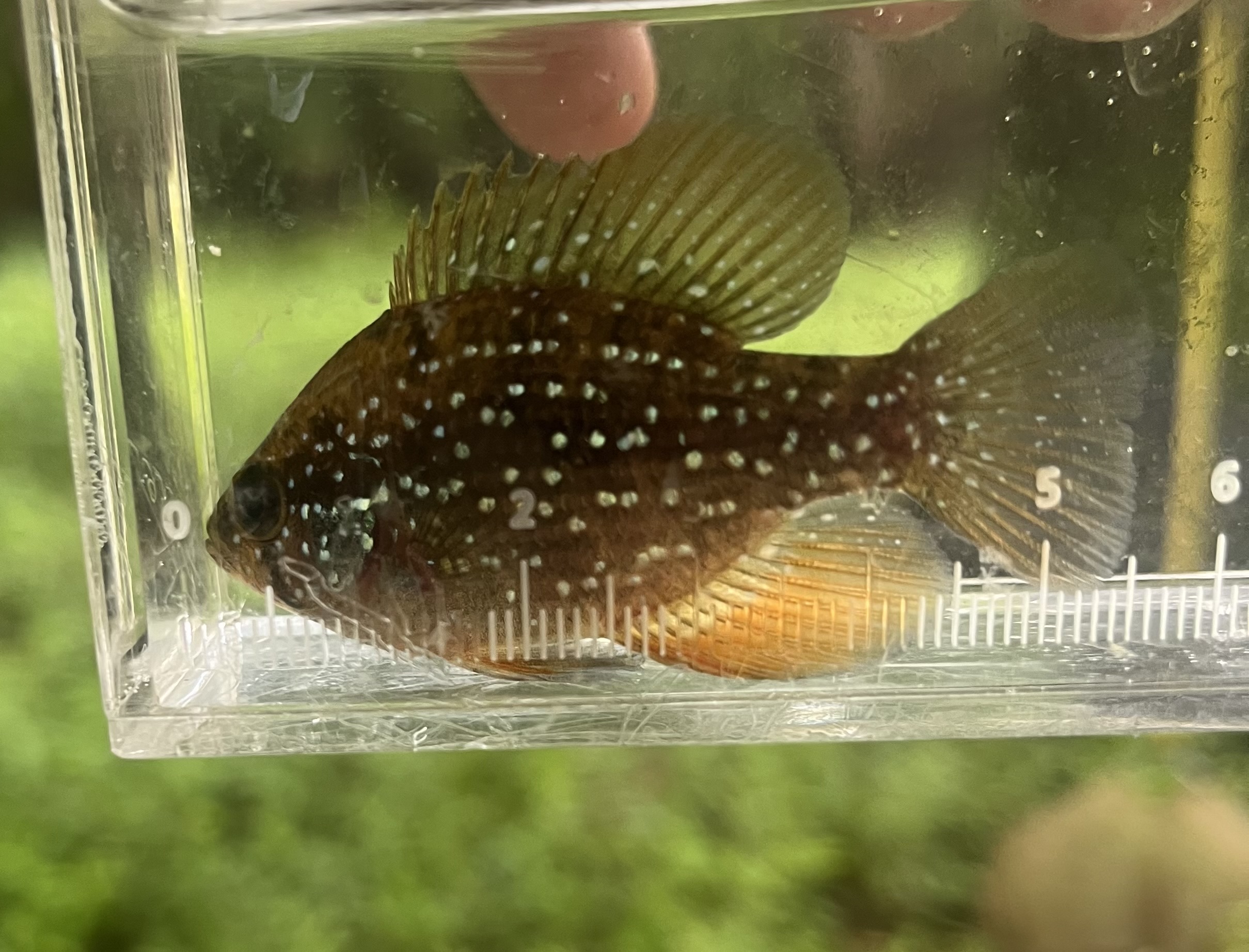

Blue-spotted Sunfish

A beautiful small fish that can grow up to 3.7 inches. They are known for their vibrant blue speckles and spots that shimmer with the light. These fish thrive among the roots and plants where they can hide.

Be Part of this Work

Protect the nature you love in North Carolina and around the world today. Every acre we preserve, every mile of coastline restored, every habitat we save for wildlife, begins with you.

After removing the culverts

We are starting our restoration phase at some sites. The plan is to conduct research after removing the culverts and start identifying fish that were only recorded downstream, swimming upstream to the floodplains. “Often times we see fish in areas with very low oxygen levels. The fish are trying to survive there—they are very resilient, but if we restore the flow and fish are moving back and forth, it will be so much better,” says Chase.

Hydrologic restoration not only allows fish to swim up the stream, but it also improves the quality of the habitat. When the water gets stuck behind culverts, it loses its ability to hold oxygen. Free-flowing water helps increase dissolved oxygen in the water. All fish species need oxygen to survive; some, such as Largemouth Bass and Bluegills, need more oxygen than others. When we see these species in restored sites, they indicate that the water quality is increasing.

Healthy functioning floodplains and barrier removal are two focal areas of our Source to Sea water program. At the Roanoke River we are also working with U.S Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to manage water releases from dams so the river can have more natural flows, which has a cascade of benefits for the forest, water quality and aquatic life