From Roots to Timber

The Expansion of Enslaved Black Labor in North Carolina’s Longleaf Pine Industry

The Author

Emmy Dasanaike was an intern in 2023. She is an honors scholar at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, studying public policy and data science.

"In understanding the past of enslaved Africans in the longleaf pine forests, we are able to better grasp the importance of conservation, especially in the role of minorities in conservation today. Even though the forests once expanded the use of slavery, The Nature Conservancy, in its restoration efforts, shifts the role of the forests from their troublesome past to a more positive role in protecting the climate." — Emmy Dasanaike.

Standing in Calloway Forest Preserve, it is easy to appreciate the natural beauty and serenity of the longleaf pine forest. The stands of trees are stoic and spread apart, allowing one to see straight through the trees, a striking experience for a stranger to the forest. The tall, scaly, longleaf pine is shaped almost like a candelabra, with long pine needles that distinguish them from the similar loblolly or shortleaf pine trees that are common here in North Carolina. Before working at The Nature Conservancy, I would never have noticed the slight differences in the conifer trees. Still, after studying the longleaf pine, I realize it is so much more than long needles that make the tree unique.

The trees are drought-, wind-, pest- and, most importantly, fire-resistant. The longleaf has a unique relationship with fire, complex enough to write a separate narrative on. The longleaf is a keystone species, as it promotes fire in a fire-dependent environment. The trees thrive in low-intensity fires, which clear the understory of the forests and allow the trees to spread their seeds and reproduce.

In their two longleaf pine forest preserves in North Carolina, Calloway Forest in the Sandhills region and the Green Swamp in Brunswick County, The Nature Conservancy uses controlled burning to maintain the forests and encourage new growth and an open space for the trees. Similarly, on his property, Lighterwood Farm, Jesse Wimberley of the Sandhills Prescribed Burn Association utilizes fire to achieve land management.

There were once 92 million acres of piney forests that stretched along the Southeast from Virginia through Texas. These forests were cleared to about 3.2 million acres, and because of restoration efforts, now stretch to 5.3 million acres. The vast clearing of these forests was a tragedy, but the hands that cut the trees were part of a more encompassing devastation. Enslaved Africans performed most of the tasks to collect the longleaf pine materials. Various newspaper clippings from the 1800s in the Southern Historical Collection at UNC-Chapel Hill show mainly enslaved Black men performing labor in the forests.

Jesse Wimberley’s great-grandfather was the overseer of a longleaf plantation, hired under a plantation owner, and the land on which he lives dates all the way back to when there was enslaved labor on the land. When visiting his farm, Jesse spoke not only of the importance of fire and conservation of the longleaf but also of the vitality of remembering the history of the longleaf and those who worked in the forests.

Since the economy of North Carolina was so immensely shaped by the naval stores and lumber industries, it is important to remember and acknowledge the labor and the adversity that enslaved Blacks endured on these plantations. In this internship, I explored the history of the longleaf and how the demand for longleaf pine products contributed to the expanded use of enslaved labor during this period in our state’s history.

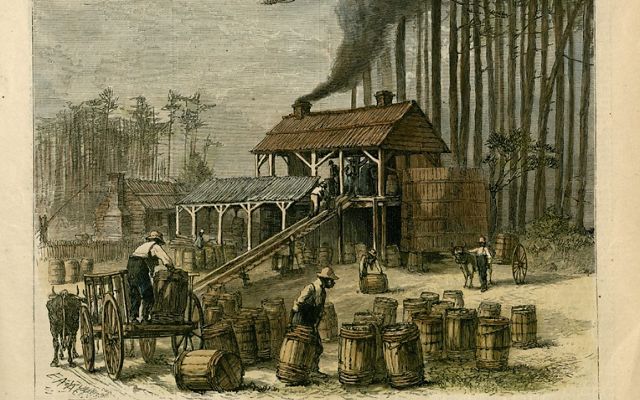

Naval Stores

According to The Journal of Southern History, the term “naval stores” originally included hemp, flax, masts, spars, planking, tar and pitch. Still, by 1800, the name had evolved to encompass tar, raw turpentine and turpentine derivatives. Tar is a thick, dark liquid that, in the forests of North Carolina, was produced by firing pine branches and logs in kilns. The substance was often spread on the ropes of sailing vessels to fortify the cords. Pitch, made from boiling tar, was applied to the outside of wooden ships to strengthen against leakage. David Silkenat, in his book Scars on the Land: An Environmental History of Slavery in the American South, states that naval stores became the South’s third largest export, exceeded only by cotton and tobacco, and processed lumber overtook cotton as a growth industry. Planters began to see forests in a new light: no longer an obstacle to eliminate before planting cotton, but instead, a valuable resource for extraction.

Shipbuilding became a major consumer of Southern timber, with shipwrights in the Chesapeake and South Carolina relying on it for masts and decking. The largest consumer of Southern timber was domestic demand, mainly for building plantation houses and enslaved laborers’ quarters, built with yellow pine, white oak and cypress. Virginia planter Landon Carter ordered the enslaved laborers on his plantation to cut down trees in the winter for fuel, and in 1770, he foresaw the devastation of the forests, saying, “I must think that in a few years, the lower parts of this Country will be without firewood.” Even early on, it was clear to many that the timber industry had a long-lasting impact on the Southern landscape.

The more sawmills, the higher the demand for enslaved labor. Close to 10,000 enslaved men worked in the turpentine forests at the height of the industry during this time, with nearly 5,000 sawmills in the region. Most industrial laborers were men, but there were some women and children, exemplified by a firsthand account from Solomon Northup, who stated that there were a few skilled lumberwomen in the Southern forests. On the turpentine plantation, laborers were made up of enslaved Africans, hired Africans and a few white laborers.

Quote: Ira Berlin and Philip D. Morgan

The legacy of slavery cannot be understood without a full appreciation of the way in which slaves worked.

Labor in the Longleaf

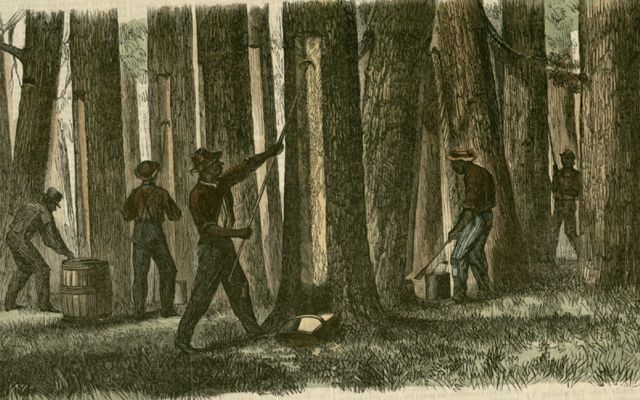

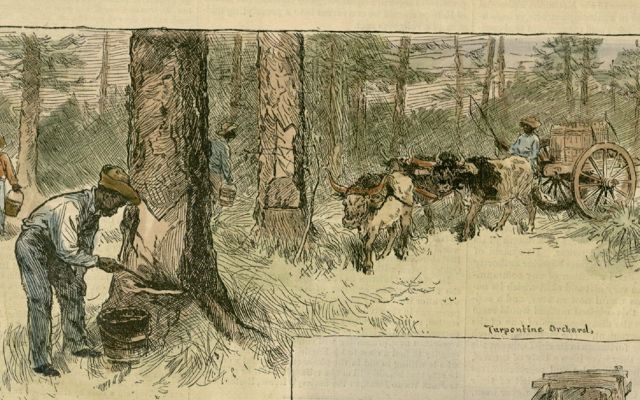

Turpentining was a seasonal practice. The trunk of a longleaf pine tree contains a system of tube-like resin canals lined with a tissue called epithelium, and once the tree matures, the canals secrete resin. Resin flows in warm weather, starting around mid-March, peaks in July and August, and ends around the beginning of November or the year's first frost. From November through March was boxing season. Using an ax with an elongated head, a hole or box is cut eight to 15 inches wide and three to four inches deep. These boxes were cut at an angle at the base of the tree trunk and could hold one to two quarts of raw turpentine. These boxes were not attached to the tree's exterior like maple sap collection but were cavities that dug into the tree. It was widely thought that new hands could not cut as well as experienced ones, so they were tasked with fewer boxes to cut. Overseers of the plantations feared that low-quality cutting would cause inadequate yield from the trees, something to be worried about when dealing with money-hungry plantation owners. A turpentine handbook of sorts for those interested in the industry recommended that “beginners will not cut at first more than 50 boxes a day, and there is nothing gained by tasking them too high until they have gotten well-used to the proper shape and size of boxes.” This exemplifies the level of skill and specificity that the overseers demanded from their enslaved labor. This seems to differ from other types of plantation labor that required little skill but a similar amount of physical labor.

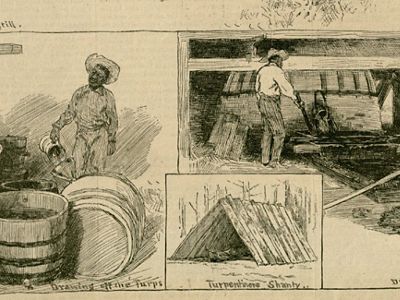

Experienced laborers were expected to cut 75 to 100 boxes per day. The largest longleaf pine tree had three to four boxes collecting resin simultaneously, quickening the collection and the depletion process. Enslaved men who collected sap from the boxes were called “dippers”; they used a paddle to scoop the sap into buckets. It was easy to tell who did this job—dippers’ hands were often covered with the gum, which was nearly impossible to remove, and they would have layers of dried sap and dirt on their skin and clothes. Inhaling the turpentine fumes was toxic for the dippers, which led to constant dizziness and raw throats. Some turpentine barons utilized women and children as dippers, although most were men. Dippers were highly skilled and could service more than 2,500 trees spread over a dozen acres daily.

While dippers collected sap, a second group of workers called “chippers,” or “hackers,” refreshed the wounds by chipping a new incision in the bark with a special ax. Sap only flowed through fresh scars, so this job ensured a continuous stream. Once the gum crystalized, chippers would return every seven to 10 days to add a new chip a mere half-inch higher than the last. As Frederick Law Olmsted stated, the chippings “sacrificed” the trees, leaving rows of gashes up and down the trunks. The scarring on the trees mirrored those on the backs of the enslaved workers, creating a cruel and violent irony. These trees were referred to as ‘cat-faced’ because of the pattern of angled slashes resembling cat whiskers. Some of these cat-faced trees can be found on longleaf preserve sites with old-growth trees, like The Nature Conservancy’s Green Swamp in Brunswick County.

Quote: David Silkenat

While environmental destruction fueled slavery’s expansion, no environment could long survive intensive slave labor. The scars manifested in different ways, but the land too fell victim to the slave owner’s lash.

Living Conditions

Enslaved workers lived in small camps deep in the woods. They stayed seasonally only for a few years, following the ebb and flow of the timber season. The housing in the lumber camps was extremely rudimentary; many lumbermen slept in shanties made from fallen timber, another example of how interwoven the lives of the enslaved people and the trees were. An observer in 1809 described these shanties as “barely wide enough for five or six men to lie in, closely packed side by side—their heads to the back wall, and their feet stretched to the open front, close by a fire kept up through the night…the roof is sloping, to shed the rain and where highest, not above four feet from the floor…the [wood] shavings…make a bed for the laborers.” This description aligns with archaeological findings from a workers’ camp at the Neale plantation from the mid-18th century.

A Changed Landscape

As stated by writer and historian David Silkenat, “Between 1665 and 1865, the environment fundamentally shaped American slavery, and slavery remade the Southern landscape,” which can be seen because “the environmental effects of enslaved labor cascaded through the ecosystem.” The lives of the enslaved Africans in the forest and the tragedy of the longleaf pine were intricately intertwined and, in some ways, even mirrored each other, an idea explored more deeply in J.D. Ho’s narrative The Tree with a Thousand Faces. The downfall of the longleaf pine came not only from the destruction and clearing of the land but also from the inability to recover.

After the boxing to collect resin, most longleaf pine trees were cut down and used for lumber. However, property owners left some behind without management, and these boxed trees were susceptible to many issues. The worst was when trees experienced something called "dry face," which happened when resin dripped through the bark of the boxed tree, permanently stopping gum flow. Sam Davis expands on this in his article The Legacy of Longleaf Pine. This condition was worsened by insects such as the IPS beetle, black turpentine beetle and turpentine borer, which attacked the trees to lay their eggs.

Water decay, fire, drought and even wind were dangers to these vulnerable trees. Longleaf bark protects the tree from fire, but chipped-away bark makes exposed trunks highly flammable. Scarified trees would explode from the intense temperatures fueled by dry wood and highly flammable dried sap. Without the bark, fire, which was once the longleaf’s main survival technique, would lead to its demise. The land felt the effects of slavery and the cruelty of the planters’ touch.

Quote: Emmy Dasanaike

There is such diversity of experiences in ecology that must be remembered to be willing stewards of the land that belongs to all and to create a focus on diversity in the conservation community. For in the pursuit of light, one cannot dismiss the darkness.

Sources:

Adams, Natalie P. “A Pattern of Living: A View of the African American Slave Experience in the Pine Forests of the Lower Cape Fear.” Essay. In Another’s Country: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on Cultural Interactions in the Southern Colonies. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

Outland, Robert B. “Slavery, Work, and the Geography of the North Carolina Naval Stores Industry, 1835-1860.” The Journal of Southern History 62, no. 1 (1996): 27–56.

Silkenat, David. Scars on the Land: An Environmental History of Slavery in the American South. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Stay Up to Date on Our Work

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from North Carolina. Get a preview of North Carolina's Nature News email.