Forever, for Texas: Krause Ranch

Meet Gary Krause, a Texas landowner preserving the beauty and natural resources of the Hill Country through conservation easements held by TNC.

Video

Conservation Easements

Gary Krause knew from the time he was a kid, tagging along while his father made his rounds to ranches as a U.S. Department of Agriculture agent in Texas, that he wanted to one day own his own ranch. When he was a college student, he even painted his vision of what that land would look like, titling it “Land I Will Buy Someday.”

About 40 years ago, Krause eventually did get his ranch—a picturesque corner of the Texas Hill Country dotted with springs at the headwaters of the West Fork of the Frio River near Leakey. Now he’s preserving the property from future development through conservation easements.

“I wanted it protected. I did not even know about conservation easements, but I knew there had to be a way to protect it so it wouldn’t be developed and ruined,” Krause says.

Conservation easements allow private landowners to retain ownership of their property but prevent future development on it. That benefits not just the property owner, but everyone — especially in a state like Texas, where more than 95% of the land is privately owned. Undeveloped land improves water quality, provides habitat for wildlife, and keeps eye-pleasing open spaces just that.

Quote: David Bezanson

I think it’s really about the quality of life for all of us. This is private land and it stays private, but the public benefits from it being there and being conserved in its current state. That’s an important thing for our country to invest in.

Krause grew up in Texas. Soon after he graduated from college, he entered the workforce, intent on earning enough money to purchase his own piece of Lone Star land. In 1983, he found it. The property had been slated to become a housing subdivision before the developer filed for bankruptcy.

“When I saw it, I fell in love with it,” Krause says. “The thought that went through my mind was, ‘How could anybody who owned this land part with it for money? Furthermore, how could they subdivide it and put a thousand people on it?’ I decided right there I had to figure out how to buy it.”

Over the next few years, Krause bought 300 acres of that land, a piece at a time. The property had been overgrazed for generations, and Krause worked hard to restore its health. He cut back Ash juniper and helped native grasses thrive, which allow the soil hold moisture. Historically, buffalo grazed the area, so he keeps a small number of cattle there to graze the property.

The springs came back. Grasses flourished. Krause occasionally rolled out a sleeping bag in one of his fields, staring up at the starry night sky. He spotted wildlife, too, including threatened and endangered species, such as black-capped vireos, golden-cheeked warblers, golden eagles and rock rattlesnakes.

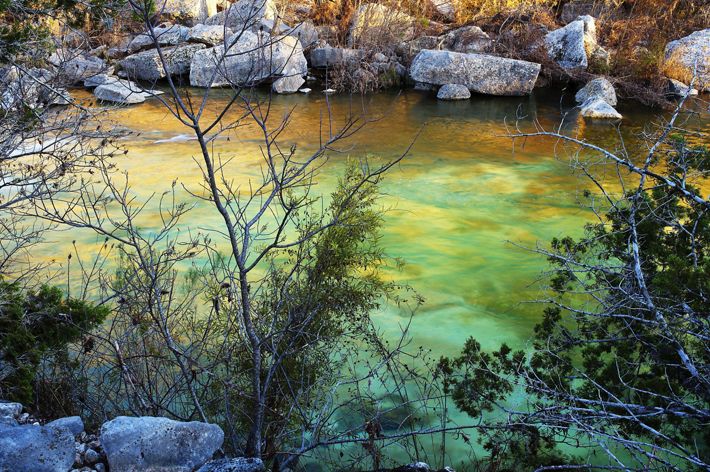

Krause Ranch now covers 1,670 acres, and Krause has lived there full-time with his wife for the past 12 years. Two places on the land stand out. One is an artesian spring that a long-term Texas Parks and Wildlife study shows contributes about a billion gallons of water a year to the Frio River, which feeds the Edwards Aquifer—a source of drinking water for the city of San Antonio. More than four additional miles of spring-fed streams and creeks on the ranch also flow into the Frio. Another is a terraced sinkhole surrounded by ferns and filled with sparkling, green-blue water.

Krause knew he had to save the land, preserving it as a benchmark for what the Hill Country looked like hundreds of years ago. He hopes that by leaving it undeveloped, scientists might conduct research there and develop best-practice techniques that will benefit other ranchers.

In 2016, Krause began working with The Nature Conservancy in 2016 to secure easements through the Natural Resources Conservation Service and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s Texas Farm and Ranch Lands Conservation Program, which are geared toward helping private landowners conserve their land. By 2019, he’d placed all but 30 acres of Krause Ranch under easements that protect it in perpetuity from development or fragmentation.

Out on the ranch these days, Krause likes to sit on the front porch with his wife, Gwen, watching and listening each evening as eagles settle along the nearby yellow bluffs and scores of buzzards ride thermals of warm air.

Krause knows places like this are disappearing from the Texas landscape as ranches are subdivided and cities sprawl into the countryside. According to the Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute, Texas loses about 640 acres of farm and ranchland each day to land conversion. Conservation easements are one of the best ways to preserve the natural heritage of the Lone Star State while also helping landowners protect their land and legacy forever.

Quote: Gary Krause

I would love for everybody who owns a large ranch to conserve it, whether it’s pristine or not, put it in conservation, keep it in one tract. You can still own it, your kids can still inherit it, it just won’t be cut into pieces.

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Texas. Get a preview of Texas's Nature News email.