From the Sky to the Rivers

A reflection on the complicated relationship of nature and Black America.

Basia Scott was the summer 2022 communications intern for TNC's Virginia Lands and Lives Project, researching historic and contemporary Indigenous communities in places where we work and exploring African Americans' traditional connections to nature. From Greer, South Carolina, Basia is studying anthropology at Wake Forest University. Read Basia's Q+A sharing her experiences.

Complex Connections

Nature is an essential part of all histories, cultures and identities. But there are some misunderstandings outside—and sometimes within—the African American community about our relationship with the land. An example of such a misunderstanding is that the community is detached from nature due to forceful displacement from Africa. Some believe the effects of this unique situation have shaped a general disinterest in the environment, conservation and ecological topics.

This is a false notion that simplifies the complex connection between African Americans and the landscape. Though our culture is vast and diverse, the roots of the African American story start and continue with nature. Despite mixed feelings across the community around water, animals and nature as a whole—coming from our collective memories of trauma—it is hard to deny that the environment shaped the past and still shapes contemporary lived experiences of African Americans.

Quote: Langston Hughes

I've known rivers: I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins. My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Practices like chattel slavery, sharecropping and lynching show how land was historically used to hurt and marginalize black populations on US soil. But nature has also served the community throughout our story. The landscape has been a venue for spirituality and a place of refuge, as well as resilience. When enslaved peoples were not allowed to attend churches, forests became their religious institutions, offering shelter, safety and connections to higher beings.

The importance of nature within this spiritual sphere of enslaved life can be seen in many ways, like through the use of environmental themes within hymns. Wade in the Water, Go Tell It on the Mountain, Jesus Is a Rock in a Weary Land, His Eye Is on the Sparrow and Take Me to the Water exemplify the significance of nature to African American spirituality. They also show the deep connection that was felt by enslaved peoples to nature, even if the land occupied a complex space within their worldview.

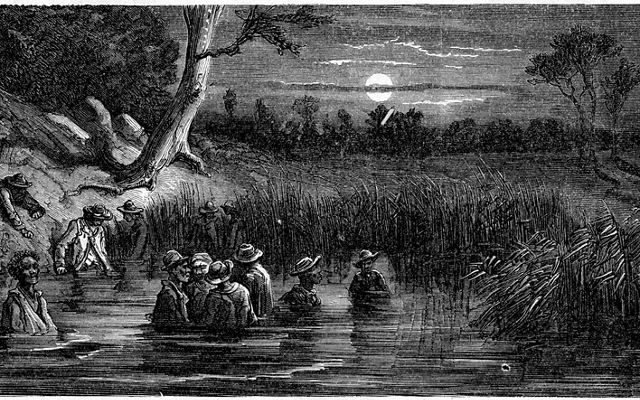

Additionally, the role of nature as a place of refuge and rebellion within African American history is incredibly salient. These roles played by nature demonstrate how the environment has been key to the evolution of experiences within the population. Varying degrees of historical black resilience and refuge can be linked to nature. One of the most important pieces of our historical tapestry can be seen in the sky. The North Star, otherwise known as the drinking gourd, served as a beacon of hope and navigational waypoint for runaway slaves seeking coveted freedom.

Similarly, the eclipse that catalyzed Nat Turner’s infamous rebellion is yet another natural element that occupies a critical space in the story of black resilience. After witnessing an eclipse in 1831, Turner took it as a sign that it was time to begin preparing for a rebellion against enslavement. Aside from the celestial, it is implicit that the forests and their waterways, in Virginia and other states alike, served as a means of cover and transport for enslaved peoples as they made attempts at freedom. More somberly, they did also serve as arenas for the hunting and mauling of those who could not evade slave hunters.

Quote: Follow the Drinking Gourd

The riverbank makes a very good road. The dead trees will show you the way. Left foot, peg foot, traveling on, follow the Drinking Gourd.

Smaller examples of nature’s involvement in enslaved resilience can be seen in the hunting of small pests, such as opossums, foxes and raccoons by these communities to gain nourishment that was denied to them. Foraging for medicinal herbs, such as mullein, sassafras and wormwood, was another way the community gained nourishment during the complicated institution of American chattel slavery. Another form of environmental refuge can be seen in the cases of maroon communities, such as those of the Great Dismal Swamp.

Maroon communities were groups of escaped individuals who lived off the land and used wild natural landscapes to protect themselves from re-capture. There were many maroon communities across the United States, the Bahamas, South America and even Africa—each unique and situated within complex trade and social networks. Nature was essential for all of these communities, serving as their home and protection from slavery.

Therefore, it is obvious that the African American community does have a very deep relationship with the environment historically. The land offered spiritual venues, grounding, protection and sustenance. These historical ties also carry into our present. We can see traces of them in church hymns, the professions of our ancestors, herbal knowledge, literature and other forms of media.

Famous Black intellects and artists, such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, bell hooks and Maya Angelou, harp on the importance of nature. They explored the conditions of African Americans through the use of natural symbolism and metaphors. They understood the connection the African American community had, and continues to have, with nature. They knew our roots run deep in the earth, not only in Africa but in America as well.

We also have contemporary connections to the environment. I believe nature still serves as a venue for fellowship and congregation, specifically in the case of cookouts. African American families and communities create vast spreads of food, dance, play and interact during these outside events, which center family and community.

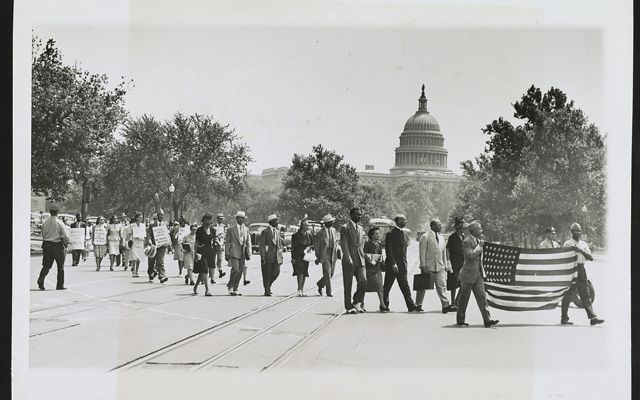

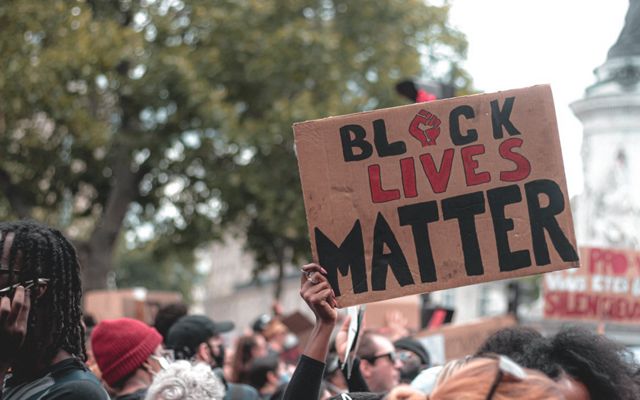

Additionally, despite most protests taking place in urban areas, they almost always happen outside. The community still uses nature as a venue for change and resilience. It is clear that the environment has served as a canvas for the African American community’s journey from chattel slavery to Black Lives Matter. The land will continue to serve this purpose if we understand its importance and partner to aid it, as it has aided us.

The hard truths of the African American relationship with the environment are many. The landscape was a medium for enslavement, lynching and inequality. This is a fact that cannot be ignored. Forced voyages across oceans separated the diaspora from Africa, and we cannot deny this.

But we also cannot deny the fact that rivers were highways to freedom; forests, our churches; and the sky, our map. If we keep running from nature and conservation efforts because of painful truths, we will lose a part of ourselves—the medium of our history—to climate change and a lack of biodiversity. African American history was born out of the land. We must recognize that we are intrinsically linked to it because of this.

It is important, then, to recognize the complexity of our relationship to nature. It's also important to do work to protect the habitats, species and natural features that have accompanied African Americans out of the past and into the present, especially if nature is to continue with us on our journey. A better understanding of the community’s relationship with natural spaces is necessary moving forward. The environment and conservation are for everyone, including African Americans, because all of our stories are rooted in, and cannot continue without, nature.

Quote: Sam Cooke

It's been a long, a long time coming. But I know a change gonna come. Oh, yes it will.

Learn More

Explore these programs that are working to re-connect African American communities to nature.

For resources and information for understanding the connection between African Americans and nature, visit Black Americans & the World of Nature—Cross-Cultural Solidarity.

Sources discussing the historical connection of African Americans to the environment:

- Cheryl LaRoche: Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad

- Michael Twitty Wants to Reconnect African Americans to Their Food

- Michael Twitty: The Antebellum Chef

To learn how you can get involved with The Nature Conservancy, visit nature.org to find events and volunteer opportunities near you.

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Virginia. Get a preview of Virginia's Nature News email