Welcome to "Field Notes," your inside look at The Nature Conservancy's efforts to preserve and restore Washington's natural beauty. Join us as we share stories from the field, highlighting our latest projects and the incredible landscapes we're working to protect.

Stay in the Loop

Get conservation stories, news and local opportunities from where you live.

Climate

Reason for Hope: New Study Highlights How Washington's Natural Spaces Can Help Fight Climate Change

September 10, 2021

The latest science coming from a partnership between The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the University of Washington (UW) highlights ways nature can help Washington achieve its net-zero greenhouse gas emissions goal by midcentury.

The study—"Leveraging the potential of nature to meet net zero greenhouse gas emissions in Washington State”—centers on how Natural Climate Solutions (NCS) harness the capacity of forests, wetlands and farmlands to absorb and store carbon dioxide that’s in the atmosphere, lessening the impacts of climate change.

What are Natural Climate Solutions?

Worldwide, nature’s power to breathe, filter and store carbon can provide more than 1/3 of emissions reductions needed to meet the Paris Agreement target. Natural Climate Solutions harness the tremendous capacity of forests, wetlands and farmlands to combat climate change. Changing how we manage, protect and restore our natural resources to be more sustainable and have a climate benefit is essential to slow the pace of climate change and its impacts on people and nature.

According to the new study, which focuses on Washington, the state’s natural spaces have the potential to capture up to 8.8 million metric tons of CO2 annually by midcentury, accounting for over 9 percent of the state’s net-zero goal. How much of the goal is met depends on how quickly and effectively solutions are implemented in these next few years before 2030 and continued over the following two decades.

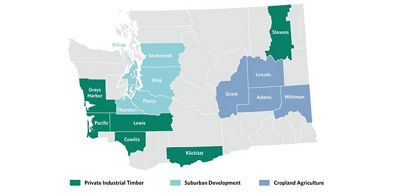

What’s unique about the study is that it offers county-level insights into which NCS options offer the greatest potential in those counties. These insights will allow local communities and leaders across the state to identify and prioritize the most effective ways to work toward the state’s net-zero emissions goal.

Quote: Jamie Robertson

Every effort matters when it comes to climate. Giving nature the chance to soak up and naturally store carbon is one, easily attainable way to make a difference.

Three big ways to better enable nature to capture and store carbon dioxide emerged in the study as having the most potential in supporting the state’s net-zero goal:

- Deferred timber harvest—logging is delayed so that trees can grow bigger and capture and store more carbon.

- Cropland management—the use of cover crops, no-till practices, and nutrient management in agricultural practices.

- Avoiding forest conversion—avoiding cutting down forests for urban, suburban and/or rural development.

Not only do natural climate solutions help address the climate crisis, they also often provide many other benefits to people, communities, economies, and nature itself. These “co-benefits” are particularly relevant for communities adapting to, and persisting through, climate change. For example, improved cropland management practices could reduce the use of nitrogen-based fertilizers, in turn reducing nitrates seeping into and contaminating groundwater (nitrate-contaminated water has been directly linked to high cancer rates, low fertility rates, increased water treatment costs and devaluation of property). Reduced use of those fertilizers would also benefit marine, freshwater and soil environments. And, if multiple NCS strategies are employed in combination with each other, the co-benefits are similarly amplified.

Highlighted clusters show where the highest-potential counties of the three highest-potential NCS strategies provide approximately half of each of those strategies’ emissions reductions in 2050. These strategies include: deferred timber harvest in Stevens, Klickitat, Cowlitz, Lewis, Pacific, and Grays Harbor counties; cropland management in Grant, Lincoln, Adams, and Whitman counties; avoided forest conversion in Snohomish, Kitsap, King, Pierce, and Thurston counties.

Further, the NCS strategies that offer the greatest impact largely coincide with and complement major economic sectors of given geographic regions—for example, cropland management is a key strategy with great potential in Eastern Washington, where agriculture is a major economic driver. This knowledge may support efficient, cost-effective and equitable approaches to NCS strategies.

It is important to note that while this scientific study from TNC and UW highlights tangible and very achievable ways to contribute toward the state’s net-zero emissions goal, NCS strategies won’t address our state’s climate goals alone—they must also be complemented by rapid and widespread emissions reductions in transportation, energy and industry sectors. When it comes to addressing the climate crisis, though, every bit of effort matters.

The opportunity to harness the power of nature through natural climate solutions shouldn’t be passed up. Not only can NCS strategies account for over 9 percent of Washington’s net-zero emissions goal, but this study opens routes to better understanding the long list of NCS co-benefits and complementary economic opportunities that NCS may provide. This supports and informs actions that give plenty of reason for hope in addressing the climate crisis.

Lands

A Season of Good Fire in Washington

December 29, 2023

When autumn rains roll in, dampening the soil and putting an end to the summer heat, Washington’s prescribed fire season really begins to heat up.

This October, Washington’s leaders in prescribed fire came together across the state to take full advantage of the opportunity to put good fire to work on our lands. From the Columbia Gorge to the northeast corner of Washington, prescribed fire training exchanges (TREX) were taking place to facilitate peer-to-peer learning and hands-on experience with prescribed fire as a practice for land management and community resilience.

WHY DO WE NEED PRESCRIBED FIRE?

Many forests and grasslands in Washington were historically fire-adapted and benefitted from low-intensity fires every 10-15 years, and cultural burning has been practiced by Indigenous peoples since time immemorial to steward these lands. In the past century, aggressive fire suppression has left people and lands more susceptible to catastrophic wildfires.

Prescribed burns are a forest management practice that uses low-intensity fire to the land to reduce dead or dying vegetation, leaf litter and small trees that can fuel larger wildfires and helps recycle nutrients into the soil. This helps forests become more resilient to wildfires and reduces the risk to nearby communities.

TREX ACROSS WASHINGTON

Training exchanges for prescribed fire take place across the U.S. and in recent years have become a cornerstone of prescribed fire and forest health management in Washington state. These events bring government agencies, Native Nations, non-profits and communities together to provide training for fire practitioners, raise awareness about the need for prescribed fire and create more resilient communities and lands in Washington.

Prescribed Fire Training 2023

This year, two TREX events were hosted in Washington—Columbia Gorge and Selkirk—bringing together more than 72 people, burning on 742 acres of public and private lands to learn from one another and grow our capacity for conducting prescribed fire.

Good Fire on the Ground: Prescribed fire practitioners execute a 6-acre burn in the Roslyn Urban Forest as part of the 2021 Cascadia Prescribed Fire Training Exchange near Roslyn, WA. © John F. Marshall

GOOD FIRE: Fire training exchanges like this one in Roslyn, Washington, build confidence and capacity for conducting controlled burns. © Kara Karboski

SAFE PREPARATIONS: Participants in a fire training exchange make preparations before conducting a controlled burn near the Wenatchee River in Washington. © Kara Karboski

Celebrting Chad Bladow: Chad Bladow, former TNC Indiana Director of Stewardship and Fire, helped lead the Cascadia TREX training in Washington and was the burn boss for the Roslyn burn. © John Marshall

This year, two TREX events were hosted in Washington—Columbia Gorge and Selkirk—bringing together more than 72 people, burning on 742 acres of public and private lands to learn from one another and grow our capacity for conducting prescribed fire. The role of TREX is pivotal as Washington and many states across the West aim to increase the use of prescribed fire as a practice for protecting our forests and our communities by reducing the risk and impact of future wildfires. To achieve our goals, we need to grow the workforce and train more fire practitioners to conduct prescribed burns.

As part of TREX, participants receive hands-on training, providing opportunity to advance their professional fire qualifications and maintain the qualifications they have already earned, learning how to prepare, conduct and clean up a prescribed burn. It also enables land managers to implement burns on both public and private lands when conditions are just right and with the help of a dedicated crew.

TNC and our partners across the state are thrilled to have had such a successful season of prescribed burns and to see Washington’s capacity for prescribed fire growing through TREX each and every year.

Water

Rain Gardens: A Beautful & Simple Solution

July 11, 2024

Written by Stephanie Koder

What exactly is a "rain garden"?

A rain garden is a bowl-shaped garden specially designed to catch rainwater from roofs and pavement. It helps to slow down the water and clean it naturally before it runs off into our streams, lakes, rivers, and ultimately Puget Sound. Without simple, natural solutions like rain gardens, rainwater picks up nasty chemicals and bacteria from our pavement and built environment. This contaminated water then rushes too quickly into larger bodies of water, where it has very harmful impacts. Untreated polluted runoff can kill an adult salmon in as little as three hours!

Although a rain garden’s main purpose is to prevent the number one polluter of Puget Sound, these natural beauties have other benefits as well. Here are just a few to get you started:

- Installing a rain garden can be a simple step to beautifying a community space or adding curb appeal to your home. The different colors and textures of stones, grasses, flowers, and plants in your rain garden will break up a boring landscape. Some communities in Puget Sound have already decided to take out unsightly and unnecessary pavement in order to add rain gardens. What a great way to instill pride and a sense of community in a local public space!

- By using native plants, rain gardens can also promote biodiversity and attract wildlife such as birds, butterflies, and bees. Of course, these creatures are fun to look at, but they are also important pollinators for growing many of our favorite local foods.

- Since rain gardens slow the flow of water, they also prevent flooding. As climate change gives our region more intense rain events, rain gardens are a plan for resiliency.

- Rain gardens are a great way to give your neighbors yard envy! Check out this video about the unquestionable community support for installing rain gardens in Snohomish County!

Polluted run-off is a very serious threat to Puget Sound waters. Rain gardens are such an easy solution for tackling this issue and reaping additional benefits along the way. If you’re still curious, one way to understand a rain garden is to see one firsthand. Click here to see where there might be a rain garden in your area.

Communities

A Year of Progress, Learning, and Community

November 14th, 2024

This year, many TNC staff, partners, and volunteers were in the field stewarding Washington’s iconic landscapes. Some were in Olympia advocating for policies that center climate and equity as top priorities for our state. Others were piloting innovative science at our preserves that will inform how we adapt our restoration efforts in a changing climate. And beyond Washington, our team worked with colleagues and partners across state lines and country borders to slow climate change and biodiversity loss at a global scale.

As we close on another year marked by climate extremes impacting our communities and landscapes, we know there is much more to do, but there is also much to celebrate. We are proud of the work we have done this year to conserve the lands and waters on which all life depends. We hope you are, too!

Your support makes a meaningful difference in shaping a sustainable future for Washington and around the globe, and I hope you will join us in celebrating these shared accomplishments. Knowing that we have a strong community of partners and supporters in this collective work gives us hope and energy for the road ahead. Thank you for all that you do.

Candid Camera: A view into Cle Elum's Wildlife

In Washington’s Central Cascades, a century’s worth of logging and fire suppression has resulted in landscape degradation that impacts water supplies and has resulted in far-reaching implications for forest and stream health, fire regimes, fish survival, and overall ecosystem function.

Maia Murphy-Williams: TNC Washington staff trip to the Central Cascades Forest. © Courtney Baxter/TNC

Cle Elum Wildlife Camera: A pilot project at Cle Elum Ridge enables TNC and partners to observe wildlife in their natural habitat in a non-invasive, low-impact way. © TNC

Cle Elum Lake: TNC acquired the lands from the Plum Creek Timber Company, including lands in the eastern Cascade Mountain Range of Washington and in the Blackfoot River Valley in Montana. © Benjamin Drummond

Cle Elum Ridge: TNC and partners are combining forest restoration, ecological fire and applied science across 10,000 acres on the Cle Elum Ridge in the Central Cascades area of WA. © TNC

Last August, members of our science and conservation teams piloted a wildlife project to monitor and evaluate how wildlife use the landscape. To gather these data, 15 motion-detecting wildlife cameras were deployed throughout Cle Elum Ridge to observe wildlife in their natural habitat in a non-invasive, low-impact way. In the coming months, we will analyze the collected data and explore how factors like recreation, proximity to water sources and trails, and snowpack impact wildlife distribution and abundance across the landscape.

This study improves our understanding of how wildlife move through protected forest landscapes. It also provides opportunities to test how forest management techniques affect wildlife, build an evidence base for permanent protection of the region, and help us determine how best to protect wildlife in the face of climate change.

Fire Fuels Reduction in a Rainforest

By Kyle Smith, TNC Director of Forest Management

Kyle Smith: TNC WA Conservation Forester, Kyle Smith, at Ellsworth Creek. © TNC Washington

Landscape of old growth forest at the Ellsworth Creek Preserve, Washington.: Landscape of old growth forest at the Ellsworth Creek Preserve, Washington. © Chris Crisman

Salamander in Rainforest.: A salamander peers over some moss. © Keith Lazelle

Timer fallers at Ellsworth: Ellsworth Creek preserve on the Washington Coast. © Lauren Owens

Measuring Ellsworth Tree: Measuring a tree in Ellsworth Preserve. © Chris Crisman

Over the 25 years that TNC has worked at Ellsworth Creek Preserve in southwest Washington, we have seen how climate change is dramatically impacting the landscape.

In response to this challenge, TNC is working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (USFWS) Willapa National Wildlife Refuge—part of a decades-long partnership to advance this work on 22,000 acres, across property lines—to test strategies to build wildfire resilience while restoring forest health and wildlife habitat. This year, we piloted innovative tools for restoration and fuels reduction, including the use of machine masticators. Traditionally utilized in dry forests, these track-based machines feature large steel teeth capable of swiftly cutting down trees and grinding them into chips. These smaller chipped pieces of wood have an increased surface area and decompose rapidly, helping to mitigate fire hazards across the forest.

We hope that these treatments will not only reduce immediate fuel loads, but will also contribute to the long-term enhancement of wildlife habitat and the progression of young forests towards old-growth forests. We are still learning how the trees will respond to fuels reduction treatment and will be monitoring and applying these learnings to our evolving approach—and sharing this knowledge so that it can be used in rainforests across the Washington coast.

zis a ba: A Big Song for Restoration

By Sara Thitipraserth, Stillaguamish Tribe Natural Resource Director, and Shawn Yanity, Stillaguamish Tribe Cultural Resource Director

Port Susan Bay: Birds take flight off the marshes of The Nature Conservancy's 4,122-acre Port Susan Bay Preserve in Washington. © Bridget Besaw

Barnum Point on Camano Island: This is an aerial image of Barnum Point, highlighting the deposits from the feeder bluffs nearby. Barnum Point on Camano Island looks out over Port Susan Bay in Puget Sound, W © Ben Drummond/LightHawk

Sunrise at Barnum Point: The sunrise paints the waters off Barnum's point as flame, and the beaches as coal. Barnum Point on Camano Island looks out over Port Susan Bay in Puget Sound, Washington. Nat © Ben Drummond

Salmon Spawning at Ellsworth.: Salmon after spawning at The Nature Conservancy's Ellsworth Creek Preserve near Naselle, Washington. Stands of old-growth Sitka spruce, Western red cedar and other conifers. © Bridget Besaw

Port Susan Bay Restoration: Flora at Port Susan Bay Preserve. © Julie Morse/TNC

An estuary is one of nature’s most important ecosystems. A place where saltwater and freshwater meet creating a unique and productive environment, supporting a vast range of biodiversity and critical habitat for countless species. Among them juvenile salmon, which rely on these sheltered food-rich waters to grow and prepare for their journey in the open ocean.

For the Stillaguamish Tribe, estuaries are far more than just vital ecosystems, they are a fundamental part of the traditional ecological landscape that supports the vitality of the Tribe’s culture. That landscape changed dramatically with the arrival of Euro-American Settlers. The Stevens Treaties of the 1850s led to the ceding of vast tracts of tribal lands, paving the way for Washington’s settlement and development. Those treaties preserved the rights of Tribes to hunt, gather and fish, rights that remain the supreme law of the land today. However, as settlers reshaped the landscape—draining wetlands, clearing forests, and altering rivers—many species the Stillaguamish Tribe depended upon saw their habitats dwindle.

Reacquiring land and restoring estuaries are a priority for the Stillaguamish Tribe, bringing back habitat critical for the survival of salmon and other species that sustain their living culture.

In late 2023, the Nature Conservancy made it possible for the Stillaguamish Tribe to reacquire 537-acres of their ancestral land, which they named zis a ba III. This acquisition is the centerpiece of the Tribe’s ongoing estuary restoration efforts, connecting the restoration lands of zis a ba I (88 acres) to the north with zis a ba II (248 acres) to the south. The acquisition of zis a ba III makes important progress towards the Tribe’s vision of a fully restored and connected zis a ba site, once again producing the plants and animals that have sustained the Stillaguamish since time immemorial.

The Work Continues

Thank you for all you’ve done to support The Nature Conservancy in our mission to conserve the lands and waters on which all life depends. Now is a pivotal time, for nature and for people. We are asking for your support as we continue to face the challenges ahead. Please consider how you might increase your impact.

Move Over Oprah, It's Book Club Time: Welcome to Indian Country 101

June 14, 2023

In February, Indian Country 101—a free, online, self-paced tribal engagement training series—was launched by The Whitener Group, a Native-owned consultant group, and The Nature Conservancy in Washington State. This new tool was created as a way to learn more about the history of Native Nations in the U.S. and how to effectively engage and support Tribes in conservation work.

Together, we’ve been building this training over the past few years for conservation-minded folks across Puget Sound. Since the training’s debut and mostly through word-of-mouth, 554 individuals have started the Indian Country 101 lessons:

- 177 TNC staff

- 70 Pew Charitable Trust staff

- 82 WA State agency staff

- 200+ individuals from other organizations across the United States

The development of the Indian Country (IC) tribal engagement series was grounded in the understanding that you can’t work with Indigenous people in the United States without first outlining the long and complicated history of tribes and tribal governments.

At The Nature Conservancy, we are piloting internal ‘book clubs’ for our colleagues to talk about what they have learned over the course of the 10 hours of training (20 hours if you also take the Washington State-focused lessons). The tools that we developed for our IC 101 Book Clubs are available for individuals or organizations hoping to host their own or reflect more deeply on their learnings.

Conversations that stemmed from the prompts were time well spent. Most were shocked over how little of this history they were taught during their formal education – with some exceptions for more recent graduates. Many of us were struck by how much we didn’t—and don’t—know about the experience of Indigenous people in North America and about the depth and duration of the systematic actions taken by the U.S. government (and others) to undermine, erase and assimilate Native Nations. We also recognized that lack of knowledge reflects that same systematic effort. We acknowledged the living reality of treaties as something that many in the environmental and non-profit world have limited awareness of, thinking instead about them as documents of the past.

Even those who had broad experience in working with Indigenous partners, still felt like they’ve stuck their foot in their mouth from time to time. We are working to approach this learning with humility. The Nature Conservancy is growing and evolving as an organization, and as individuals. Our goal with the book club is to work toward creating a culture of learning and personal growth—being kind to each other while also truth-telling. Our shared challenge is how we might consider our work with Indigenous Landscapes and Communities in ways that are not business as usual but elevate our partners’ sovereignty and leadership in decision-making. We are considering how we might show up differently in both Native and non-Native spaces, and whose burden it is to build this culture within our organization. We welcome conversation about what it means to get comfortable with getting uncomfortable and talked about what our future as an organization looks like if we do this work well:

- Equity is integrated into all systems and structures of our organization, with leadership elevating examples of equity and providing resources for the work to happen

- Non-Indigenous actors reconcile colonialization, white supremacy, power imbalance, broken treaties

- Our institutional norms and incentives lead with humility that respects and honors Tribal sovereignty

- Indigenous voices and leadership are leading/advising global work and impact

- We embody what it means to be a guest in North America, changing HOW we work

Get Started

Take the Indian Country 101 TrainingAre you now chompin' to start your own Indian Country 101 book club? We've got you!

Resources

-

- What surprised you about this training so far?

- Is this new info for you so far, or did you learn about this in school?

- Did any part of this training strike a particular emotion in you? Which part and what emotion did you feel?

- If we were to do Tribal Engagement well, does it seem like it would require a big mindset shift for your organization or a small one? Why?

- Did the training change your opinion about anything, or did you learn something new from it? If so, why?

- Compare this to other trainings on tribal engagement that you’ve done. How was it the same or different?

- What was your favorite part of the training so far? Did you have a favorite quote or voice that was highlighted? If so, share which and why?

- What does it mean to put this into practice within your organization?

- What do you think your first step might be to putting tribal engagement into practice within your organization?

- Are there things we do/areas of work where you now see a different perspective?

-

- Print your Quick Reference Guide. Review the Want to Know More?, Organizations to Know, and People to Know sections throughout the courses. Visit the listed websites on your own.

- Go through lessons again!

- Attend a tribal event! Be comfortable with being uncomfortable at first if you are!

- Find a Native friend that is ok with (as in check with them to make sure you aren't assuming they are ok with spending the time with you to do that) helping you learn more about tribes; you gotta find an in! But don't be fake and weird about it of course.

- Buy some Native products! And NEVER EVER EVER again buy any tribal art if you can’t easily tell the tribal artist’s name and tribal affiliation.

-

- IC:101 Quick Reference Guide - an AMAZING excel spreadsheet that consolidates quick tips, critical info, and definitions learned in the training

- SAMHSA Culture Card

- Social Media Press Kit + Graphic Assets to help spread the word about IC:101

- More IC101 Resources

Note:

You don’t get any sort of ‘certificate’ for going through this training, but you do get an awesome IC:101 Spotify playlist.