Helping Washington's Coastal Forests Prepare for the Future

By Sara Adams, freelance writer

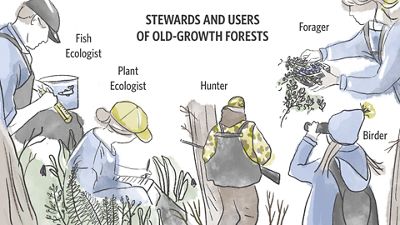

The coastal forests of the Pacific Northwest are integral to our way of life. Hunters, foragers and recreators alike delight in their offerings. Sustainable harvesting is an important part of our economy and source of local jobs. They help keep our water clean, rivers healthy and provide habitat to wildlife.

However, as we turn the page on the hottest year on record, we are reminded of the challenges facing our forests. While dry forests experience more severe wildfires and drought, coastal wet forests must contend with a unique set of circumstances, such as changes in land use, increasing insects and disease, and extreme weather events.

With climate change compounding these stressors, there is an urgent need to prepare our forests for the future. But, how?

The answers lie deep within the old-growth forests of the Ellsworth Creek Preserve, nestled on Washington’s southwest coast. New research offers land managers a way to cultivate characteristics that will help tomorrow’s forests adapt to an ever-changing environment.

Restoring Old-Growth Forests in the Pacific NW

Read a high-level overview of the scientific paper featured in this story over at Cool Green Science.

Ellsworth Creek Preserve: A Living Laboratory for Forest Resiliency

When The Nature Conservancy purchased the Ellsworth Creek Preserve in 2001, just a fraction of the old-growth forest remained. To better understand how the ecosystem was changing, the 7,600-acre watershed was divided into experimental sections. Different strategies were applied across sections to understand whether the development of old-growth forests from dense, young forests could be sped up. “We thought we had good ideas of how to restore this entire landscape—we cut some trees, decommissioned some roads and then we measured and waited,” says Dr. Michael Case, forest ecologist with The Nature Conservancy in Washington.

Researchers found when it comes to old-growth forests, there is more than meets the eye.

“Ellsworth Preserve is more than a living laboratory. It’s an opportunity to observe the forest, articulate its value more comprehensively and ensure this land can continue to provide those varied benefits,” notes Dr. Case.

In the preserve, 800-year-old Sitka spruce and western red cedar trees tower above. Cougar, black bear and elk find home in the forest, while birds fly up high. The Ellsworth Creek, which flows through the preserve, provides critical habitat for spawning salmon and amphibians.

In viewing this landscape through the lens of many different stewards and users, each layer adds richness and a deeper understanding of what makes an old-growth special. While a hunter might look to the woody debris and snag for camouflage, a member of the Chinook Indian Nation might harvest wild huckleberries and a birder might spot an orange-crowned warbler in the canopy.

A Hallmark of Biodiversity and Resilience

Forests are critically important for carbon sequestration and storage. Due to their age, amount of precipitation they receive and longer intervals between fires, the Pacific Northwest’s coastal forests are known to store significantly more carbon than other regions—80 megagrams per hectare. That’s nearly double the amount stored by midwestern forests and a quarter more than forests in the Northeast.

In addition to sopping up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, old-growth forests may be better at adapting to a changing environment than younger forests. But, why is that?

Old-growth forests are home to a diversity of trees, plant and animal species. Natural processes create more space for trees to spread out. Over the course of hundreds of years, the forest floor becomes more textured with fallen branches and logs. In turn, these layers become habitat or starting points for new growth. As compared to a younger, more structurally simple forest, the species in an old-growth forest compete less for resources and can sometimes weather drought better. They also contain “climate refugia,” areas that buffer changes in the microclimate—the climate of a specific area as compared to surrounding areas—helping stabilize temperatures.

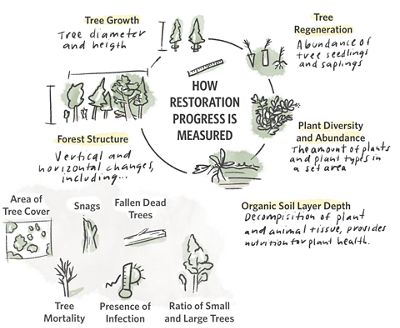

There is a tiny fraction of old-growth remaining in the Pacific Northwest. Scientists, like Dr. Michael Case, forest ecologist with The Nature Conservancy, have been looking for quick ways to develop the forest structure (the horizontal and vertical distribution of the layers within a forest) and plant composition seen in old-growth forests in areas that were previously logged. New research out of the Ellsworth Creek Preserve offers insights into how we can accelerate the development of the old-growth traits that help forests persevere through the most severe impacts of climate change.

Selective Thinning: An Important Tool in the Adaptation Toolbox

Dr. Case and his team found that carefully removing some trees, a restoration technique called selective thinning, helps recreate the look and feel of an old-growth forest. When the density of the forest section was reduced by 30%, the remaining trees had enough space and resources to thrive and may better withstand drought. Enough tree canopy coverage was preserved to ensure the understory, the layer of vegetation under the tree canopy, could still buffer against climate impacts.

Because there is no single indicator to measure restoration success, the team looked at a number of indicators to understand how well selective thinning was working.

Given the complexity of these ecosystems, continuously monitoring changes is critical to developing a comprehensive understanding of the impact of restoration treatments. “A key takeaway is that ongoing monitoring and adaptive management practices, rather than ‘one-and-done’ treatments, are more likely to achieve a full suite of old-growth characteristics that best support habitat and climate resilience,” says Dr. Case.

Watch “A Day in the Life”

Watch, “A Day in the Life," a new short film featuring Michael Case and TNC in Washington’s Science Team, who every day provide the knowledge crucial for a future where people, lands and waters thrive in balance.

Helping Coastal Forests Prepare for the Future

Places like Ellsworth Creek Preserve are necessary for embracing the complex solutions demanded by big restoration questions. This research is just one piece of a broader agenda to improve the health of Washington’s forests.

The preserve is helping provide the best available science for local, state, federal and Indigenous agencies responsible for managing our land and forests throughout the region. This is especially important as the Northwest Forest Plan undergoes revisions to address the issues of today and prepare for tomorrow. The plan is used by federal land managers to make decisions about 24.5 million acres of forest (roughly 10x the size of the Olympic Peninsula or comparable in size to the state of Maine) in Oregon, Washington and California.

On the horizon, Dr. Case is part of a multidiscipline team building a carbon mapping tool that identifies opportunities for forest carbon conservation throughout the entire Emerald Edge, the world’s largest coastal temperate rainforest, extending from Oregon and Washington to British Columbia and Alaska.

The tool categorizes areas by landowner type. This facilitates direct engagement and informed decision-making to best meet the landowner’s social, economic and cultural needs while maximizing ecosystem benefits like carbon storage.

By looking to the past, we can help Washington’s coastal forests prepare for the future.

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Washington. Get a preview of Washington's Nature News email.