Solutions for Cities and Salmon

In Puget Sound, we’re making cities more resilient and livable by developing green infrastructure and natural solutions to pollution.

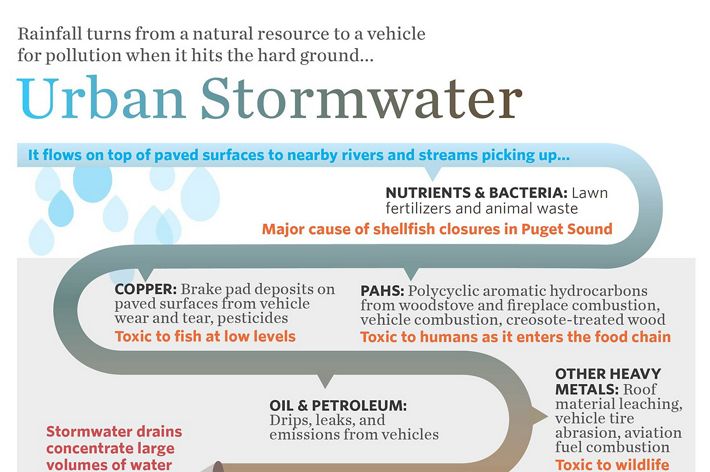

It’s another rainy day in Seattle. In the city’s Fremont neighborhood, stormwater flows off the Aurora Bridge, which spans the waterway that connects urban Lake Union to Puget Sound. The stormwater, which fell as rain, is now laden with chemicals and metals from rubber tires, brakes, motor oils, antifreeze and other sources.

Every year, 2.3 million gallons of highly polluted stormwater runoff rolls off the north end of this one bridge into the Fremont neighborhood. It seems destined to contaminate the water below—a key route for migrating salmon—and end up in Puget Sound.

In fact, an astounding 75 percent of the toxic chemicals that enter Puget Sound come from stormwater runoff. Our data show that there are 359,500 acres of impervious surface in the Puget Sound, or about 560 square miles. That’s more than 272,300 football fields of asphalt, concrete and metal where rainwater washes off without being taken up by trees or seeping slowly into the ground.

Just one acre of pavement can put a million gallons of polluted runoff into Puget Sound each year. And in urban waters like Lake Union, stormwater may kill up to 80 percent of migrating coho salmon before they have had a chance to spawn—significantly higher than the 1 percent mortality rate that occurrs naturally for pre-spawn salmon.

Creating Better Cities, Naturally

At TNC in Washington, we know that our cities, habitat and salmon are profoundly connected by water, from those hallmark rains to our rivers and Puget Sound. We understand that by improving how people, development, water and natural infrastructure interact, we can have a positive, powerful impact on water quality, salmon and our own lives.

Through our Cities program, we’re forging partnerships and promoting strategies that improve water quality as it flows through our urban places. For example, our research partners have demonstrated that simply passing stormwater through natural material like sand and compost filters out many toxins, restoring water to a safe, clean quality that supports salmon. This “green infrastructure,” incorporated into cities as rain gardens, swales and thoughtfully designed diversion and filtering structures, also do double duty as green spaces where city dwellers can bask in a slice of nearby nature. That is proven to have wide-ranging benefits for mental health as well as physical wellness.

Puget Sound is growing fast: More than 80,000 new people move here every year. Now is the time to plan for the future, making our cities better for Puget Sound, salmon and people. Two inspiring projects are examples of how we are doing just that.

Clean Water Under the Bridge

Fremont, the lively, funky neighborhood surrounding the Aurora Bridge, buzzes with coffee shops, breweries and thriving software companies. Developer Mark Grey of Stephen C. Grey & Associates was just beginning work on a new office building there when he saw a video about the devastating effect untreated storm water has on salmon.

Grey wanted to help. With the proposed new building located directly beneath the Aurora Bridge, he realized he was in a unique position to make a difference. Grey contacted Salmon Safe—a certification and accreditation program for new buildings, farms, wineries and other development to ensure land-management practices that protect watersheds—to explore how the new building could help protect waterways.

With help from TNC and Salmon Safe, developer, architects and engineers were able to navigate the complex permitting and regulatory process that allowed them to divert stormwater runoff from the Aurora Bridge into a series of cascading raingardens along the new building. In addition to such surface features, the project also involved rerouting downspouts from the bridge, installing an underground holding vault to capture excess runoff and additional public utility, cost and design components.

The project—which is at the intersection of transportation, surface-water runoff, green infrastructure and building design—blazes the permitting and regulatory trail. This is a success story for how TNC and partners can forge public-private solutions to break policy roadblocks and accelerate change.

After three phases of green-infrastructure development, the Aurora Bridge project will filter and treat 2.3 million gallons of heavily polluted runoff annually to high standards of water quality. It also provides a welcoming natural environment for residents and workers.

Remove Pavement, Discover Roots

Just south of Seattle, in the city of Kent, rain no longer flows unchecked across a cracked asphalt parking lot. Instead, rainwater collected in cisterns waters a flourishing community garden, where immigrants and refugees from all over the world find a renewed connection to the soil, to their culinary roots and to each other.

The transformation from pavement to community garden was fast. With leadership from refugee resettlement organization World Relief Seattle, generous donation of the unused parking lot by Kent Hillside Church and support from partners including TNC, it took just months. More than 1,000 volunteers removed the 20,000-square-foot parking lot and built a community garden in its place.

The Hillside Paradise Parking Plots garden boasts 50 separate plots, four 4,000-gallon cisterns, a tool shed and a blossoming community centered on gardening, culturally familiar foods and a connection to the soil. Now the garden is looking to complete its rain gardens and bioswale to capture more of the water flowing across the parking lot and plant trees to shade the plots.

Of course, converting pavement to a runoff-filtering garden has great trickle-down benefits for water, habitat and salmon as well. The rain garden will collect and filter stormwater runoff from 90,000 square feet of surrounding streets and parking lots. It’s also an island of cool that helps reduce urban heat. In this inspiring place, solutions to stormwater runoff intersect with human wellness in the best possible way.

Reimagining Our Cities

Puget Sound’s cities, communities, rivers and sound and iconic salmon are deeply connected through water. Yet, stormwater runoff is one of the greatest threats to the health of this fast-growing region.

By designing our cities to function more like forests, where rain percolates into soil for a filtering effect, we can help solve our stormwater problems. Using green infrastructure and the power of partnerships, we are re-imagining Puget Sound’s urban places as good for nature—and good for people.