Quote: Dr. Emily Howe

Lessons from the Marshy Middle

Leah Palmer, TNC Writer/Editor recites her poem, "Lessons from the Marshy Middle," an homage to the estuary at Port Susan Bay Preserve in Washington.

The way of connection is revealed by water—snowy summits melting, forging rivers, winding streams and cutting wetlands to spill over a salty edge.

The shape of kinship is mapped in our bodies, veins and arteries transporting blood, nutrients, and oxygen.

The sound of restoration is a mother’s whisper—Constant. Remembering, tending, protecting, growing. She provides, “I am with you.”

The pattern of healing is a symphony of breath— a song of right relations, each anticipating the next measure.

The way of connection is revealed by water—snowy summits melting, forging rivers, winding streams and cutting wetlands to spill over a salty edge.

Discover More Stories Like This

Send me Emailsby Leah Palmer, TNC Washington Writer/Editor

Dr. Emily Howe’s words are unequivocal, like a rising tide pushing through the eelgrass, bulrush and Carex of Port Susan Bay Preserve. As she tends watersheds, she is a fierce observer of liminal spaces—where boundaries are elusive. On first glance, the estuary seems as if it can be known immediately—grass, water, sky. But, to understand its vital contributions to life on the coast, as well as to witness its poetry, one must understand it is situated in the middle. Emily explains that the estuary is a critical site of connectivity, holding fresh snowmelt, the Stillaguamish River and seawaters all in one place. Unobstructed connections generate a habitat rich in biodiversity while supporting climate resilience.

The dynamic nature of Port Susan Bay keeps Emily and her collaborators busy monitoring channels that are cut deep, marshes that grow thick and mudflats that spread wide. It is a nursery for juvenile salmon, momma seals and their pups, osprey and eagles. It is also a critical feeding stopover for migratory birds, oscillating across the sweep of the Pacific Flyway each season. The estuary is “more transitional than most because it’s part land and part sea,” says Emily. “It's part fresh water and part salt water. And it changes across those realms every hour of the day. It is constantly shifting, switching back and forth.”

Emily says, “It's a place of dynamic balance.” The plants and animals that survive in this space are resilient. “Everything is both robust and fragile at the same time. The plants are living at the very edge of their physiological capabilities, making them pretty tough.” She notes, “They can shift between fresh and salt water,” yet they live in a fragile system, “all competing.” The edges are “really sensitive places to pick up change, from a scientific perspective. You’ll see shifts easily.” Her data show this preserve is a “sentinel for climate change in nursery habitats and for so many marine organisms.”

But the estuary does not survive independently. Its health and biodiversity are significantly influenced by the health of waters filtering through it and flowing out to Puget Sound. In 2015, there was a severe drought—caused by a poor winter snowpack—that deeply impacted the marsh, taking Emily to the summits of the Cascade Mountains to understand how changes in forest management impact snowpack and eventually the marsh. Not long after, she and collaborators turned their attention to quantifying the severity of pollutants in water runoff from cities and neighborhoods, resulting in a groundbreaking stormwater heatmap tool. Individually, each research project is stunning. But as a collection, this body of work reveals that water connects us all.

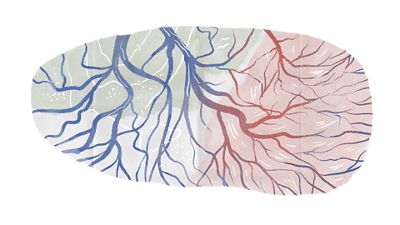

The shape of kinship is mapped in our bodies, with veins and arteries transporting blood, nutrients, and oxygen.

An aerial view of Port Susan Bay reveals a familiar structure: channels are carved into the wetlands like the human circulatory system, stretching nutrients to the outer extremities of the land. Rivers are like major arteries and veins. The marsh’s smaller channels parallel the body’s capillaries. Emily notes, “Main systems branch out into smaller and smaller and smaller ones until you’re out into those capillaries.” Fascinatingly, she goes on, “The salinity of an estuary is similar to the salinity of our blood.”

Since time immemorial, Indigenous Peoples have lived along the Stillaguamish River Basin, preserving the valuable connections of these systems. Traditionally, they maintain a reciprocal relationship with salmon—tending to their habitat, observing their needs and ensuring a thriving ecosystem—as the fish provide nutritional and cultural gifts for human life. Yet, introductions of European water and land management practices significantly encroached on Indigenous ancestral ways. The Stillaguamish Tribe was forced to relocate to the Tulalip reservation due to a misinterpretation of the Point Elliot Treaty of 1855, leaving the estuary vulnerable to new management practices. In 1974, the landmark Boldt Decision reaffirmed Stillaguamish treaty rights to the river basin. But, in those interim 129 years, the waterways were deeply altered. Europeans implemented sea dikes and river levees to hold back seasonal floodwaters and natural tidal swells that threatened corn, peas, potatoes and other crops.

For decades, the Stillaguamish Tribe has fought to reacquire ownership of the treaty lands, sharing a vision for restoring the lands surrounding Port Susan Bay Preserve. The Stillaguamish Tribe acquired the third and final section of a set of lands they have named zis a ba, located at the mouth of the Stillaguamish River. The Tribe and TNC have partnered with a shared vision to restore the delta habitats using adaptive management practices—a land stewardship method driven by a generative learning-by-doing approach, which includes a cycle of implementing projects, monitoring, science and adapting actions in response to learning.

Emily says colonial modifications significantly impacted the health of this nearshore environment, including the parcel TNC manages. Colonialism “created a system where we only have the main veins and arteries. It's channelized, stuck between levee walls.” In a body, this is like depriving one's extremities of crucial oxygen and nutrients. A river and its marshes should be able to swell with the tide and rains, like taking in a deep breath.

In her snowpack research, Emily poignantly warns, “Now planted solidly in the Anthropocene, the Earth overwhelmingly bears the marks of humanity. Some marks are ingenious and beautiful. Some forgotten, long since folded back into the soils of time. But when the legacies we leave tinker with the natural laws of biophysics, they don’t allow us to forget.” While humanity often forgets—sometimes fighting the natural laws that hold us all together—water remembers. Emily learned this principle from Indigenous water keepers who teach water’s ability to carve a way back to an intended home. The snowpack essay continues, “What goes around, comes around. For each force, there is an equal and opposite reactive force.”

There is an equal reactive force for the wounds Port Susan Bay bears. Her hope rests in “letting the softness of the edge return and letting the water come home,” according to Emily.

The sound of restoration is a mother’s whisper—constant. Remembering, tending, protecting, growing. She provides, “I am with you.”

Field research requires Emily to form a familiarity with her environment. At Port Susan Bay, she developed an intimacy with the marsh—wading through early mornings, kneeling in tall grass, observing each blade, discerning diatoms and tracking the sun’s power to break down organic matter in shallow waters. She calls this mix a “soup” that “supports the next group of creatures all the way out to nearshore fisheries.” Spoken like a friend of the estuary, she says, “I just love that mix. It makes me happy.”

Her joy comes from contributing to the variability of the habitat, strengthening each species’ shot at climate resilience and adaptation. She’s a nurturer, witnessing the results of her dedication, despite frightening degradation. Emily emphasizes the importance of biodiversity and habitat restoration working to ensure climate resilience. “If we only were to focus on climate change, thinking climate mitigation would save us from the biodiversity crisis, we would be remiss. We were losing a lot of species and a lot of ecosystem integrity, functions and processes before the climate crisis reared its head.” The climate crisis is simply intensifying the wounds we already made.

As such, she and TNC in Washington’s stewardship team identified a need for habitat restoration throughout the estuary. They worked to reconnect the waterways, drawing deeply from data developed across decades and eventually stewarded by Emily, with support from Skagit River System Cooperative. Her familiarity with the natural design and function of the nearshore helped shape a plan for restoration.

Initially, TNC believed work at Port Susan Bay would wrap quickly after completing restoration efforts in 2012. But, five years of intensive post-project monitoring revealed an entirely different story. “We listened to the marsh through those data,” Emily says, referencing prose from fellow scientist Robin Wall Kimmerer:

“[Data] are just ways we have of crossing the species boundary, of slipping off our human skin and wearing fins or feathers or foliage, trying to know others as fully as we can. Science can be a way of forming intimacy and respect with other species that is rivaled only by the observations of traditional knowledge holders. It can be a path to kinship.... Heart driven scientists whose notebooks, smudged with salt marsh mud and filled with columns of numbers, are love letters to salmon. In their own way, they are lighting a beacon for salmon, to call them back home.” (Braiding Sweetgrass, 2013, p. 252)

In late summer 2023, the adaptive management team completed work to restore broken connections in the estuary by digging new channels that mimicked pre-colonial networks. Their work and dedication to biodiversity significantly bolsters resilience to climate change. Emily says, “The climate is going to get refracted by the landscape that it hits.” A place that is degraded will fare worse than one that has been carefully tended. Furthermore, if degradation was caused by human impact, Emily says there’s hope. “We can actually roll back our legacy to a place that looks more like the natural system and structure that had been there before.”

The pattern of healing is a symphony of breath—a song of right relations, each anticipating the next measure.

The pattern of healing is a symphony of breath—a song of right relations, each anticipating the next measure.

Today, Emily’s crucial insight informs conservation projects beyond Washington's borders. Recently, she is tackling a science review for the Bureau of Reclamation, which aspires to reinforce the health of an industrialized water system in California. “It’s much bigger than myself,” she says of the unbelievably channelized dams, aqueducts, reservoirs and pumping systems humans have implemented to balance flooding and droughts in the Golden State. “That system in California is incredibly stressed. And that stress is moving up the coast.” She wonders what Washington’s systems will be like when they reach a similar level of stress. Emily admits, “That keeps me up at night.”

Despite her uncertainty about the future of Washington’s waters, Emily is sure about one thing. There is a symphony of advocates for fresh water and nearshore habitats, including a range of experts—from skillful storytellers to passionate policy practitioners. Each joins broader efforts to restore and reconnect waterways for a biodiverse habitat and a climate-resilient future. Still, she says the most valuable contributors to this work, and often the least funded, are those with an intimate relationship to the watersheds. They show up in salt-stained waders, navigate through fields of marshy grass, record data in notebooks, petition for funding, observe biodiversity comebacks and educate the rest of us along the way. They are both informed and hopeful. She draws from her friend’s reflections on hope, published in The Seattle Times, saying, “A hope that is not paired with honest assessment is not useful. It's a falseness. We always need hope...to get people through hard things, hard times. But things don't get better unless you put out effort.” Emily and her collaborators prove their hope with dedication to their love song to salmon.

“Lessons from the Marshy Middle”

By Leah Palmer/TNC

The way of connection is revealed by water—snowy summits melting, forging rivers, winding streams and cutting wetlands to spill over a salty edge.

The shape of kinship is mapped in our bodies, veins and arteries transporting blood, nutrients, and oxygen.

The sound of restoration is a mother’s whisper—Constant. Remembering, tending, protecting, growing. She provides, “I am with you.”

The pattern of healing is a symphony of breath— a song of right relations, each anticipating the next measure.