Environmental disasters in the U.S. often hit minority groups the hardest.

When Hurricane Katrina slammed New Orleans in 2005, the city’s black residents were disproportionately affected. Their neighborhoods were located in the low-lying, less-protected areas of the city, and many people lacked the resources to evacuate safely. Similar patterns have played out during hurricanes and tropical storms ever since.

Massive wildfires, which are becoming more frequent due to climate change and a long history of fire-suppression, also have strikingly unequal effects on minority communities, a new study shows. This study is one of the first to integrate both the physical risk of wildfire with the social and economic resilience of communities to see which areas across the country are most vulnerable to large wildfires.

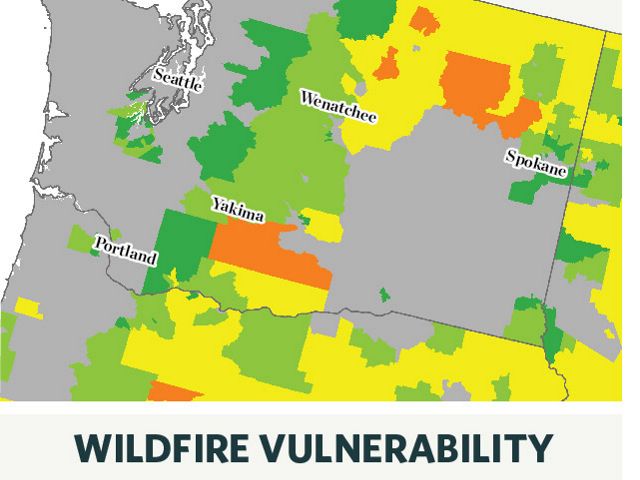

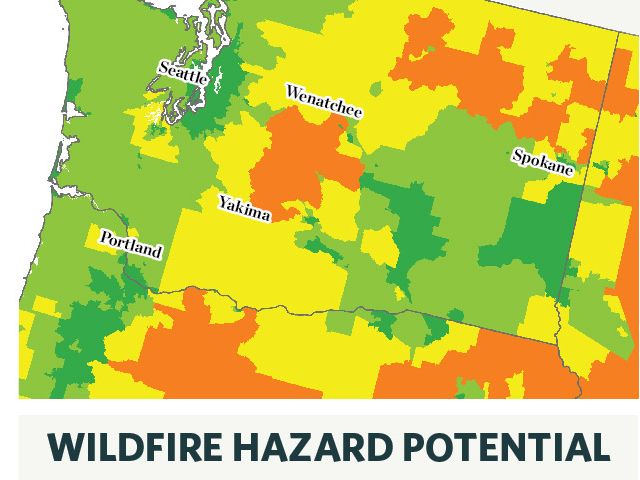

Researchers at the University of Washington and The Nature Conservancy used census data to develop a “vulnerability index” to assess wildfire risk in communities across the U.S. Their results, published in the journal PLOS ONE, show that racial and ethnic minorities face greater vulnerability to wildfires compared with primarily white communities. In particular, Native Americans are six times more likely than other groups to live in areas most prone to wildfires.

“A general perception is that communities most affected by wildfires are affluent people living in rural and suburban communities near forested areas,” said lead author Ian Davies, a graduate student in the UW School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. “But there are actually millions of people who live in areas that have a high wildfire potential and are very poor or don’t have access to vehicles or other resources, which makes it difficult to adapt or recover from a wildfire disaster.”

The approach takes 13 socioeconomic measures from the U.S. census — including income, housing type, English fluency and health — for more than 71,000 census tracts across the country and overlays them with wildfire potential based on weather, historical fire activity and burnable fuels on the landscape.

Overall, more than 29 million Americans — many of whom are white and economically secure — live with significant potential for extreme wildfires. However, within that segment, about 12 million people are considered “socially vulnerable” to wildfires, and an extreme fire event could be devastating.

Communities that are mostly black, Hispanic or Native American experience 50 percent greater vulnerability to wildfires compared with other communities.

In the case of Native Americans, historical forced relocation onto reservations — mostly rural, remote areas that are more prone to wildfires — combined with greater levels of vulnerability due to socioeconomic barriers make it especially hard for these communities to recover after a large wildfire.

“Our findings help dispel some myths surrounding wildfires — in particular, that avoiding disaster is simply a matter of eliminating fuels and reducing fire hazards or that wildfire risk is constrained to rural, white communities,” said senior author Phil Levin, a UW professor in environmental and forest sciences and lead scientist at The Nature Conservancy in Washington.

The researchers hope these broad, nationwide results will spawn more detailed studies focused on individual communities and their wildfire risk. But equally important, they say, is for organizations and municipalities to take these socioeconomic factors into account when helping their communities prepare for wildfires. Offering cost-share programs for residents to prepare their homes for wildfires, distributing evacuation notices in multiple languages and creating jobs focused on thinning local forests or clearing out flammable brush are all ways in which communities can reduce their vulnerability to wildfires.

“I think ultimately it’s about connections, building relationships and breaking down cultural barriers that will bring us to a better outcome,” Levin said.