Western Dry Forests and Fires Stories

Can we drink the water?

Why we need our forests now more than ever

By Dustin Solberg, Writer/Editor for The Nature Conservancy

We all depend on the power of forests for clean water.

Each and every one of us drinks water. In our homes and wherever we go, it’s hard to imagine a day without clean water. It’s there at the kitchen tap. Clean water bubbles up from drinking fountains in our neighborhood schools. Water quenches our thirst on hikes in the mountains and it’s what recharges our kids when they play hard.

It may seem that clean water is simply piped from water treatment plants and into our homes. In reality, most of the water we drink starts its journey in forests—the best water filters on Earth. That’s the power of forests at work in our lives.

But forests need our help. Keeping these forests healthy and green—or bringing them back so that they are—takes work.

So we’re introducing you to a number of individuals who, in their own unique way, want to tell us something important about the water we drink. Through their work on the ground and what they themselves have seen, they know firsthand how healthy forests connect us to clean water. Their efforts for the forest are adding up in ways you can see. And that keeps clean water flowing, drop by precious drop, into your every glass and cup.

Why we need our forests now more than ever

What TNC is Doing

TNC’s Western Dry Forests and Fire Program aims to put 50 million acres of forests in the U.S. and Canada on a trajectory to increased health and resilience by 2030—avoiding catastrophic wildfire and keeping clean water flowing to our taps in towns and cities all across the West.

Why clean drinking water needs forests—and fire

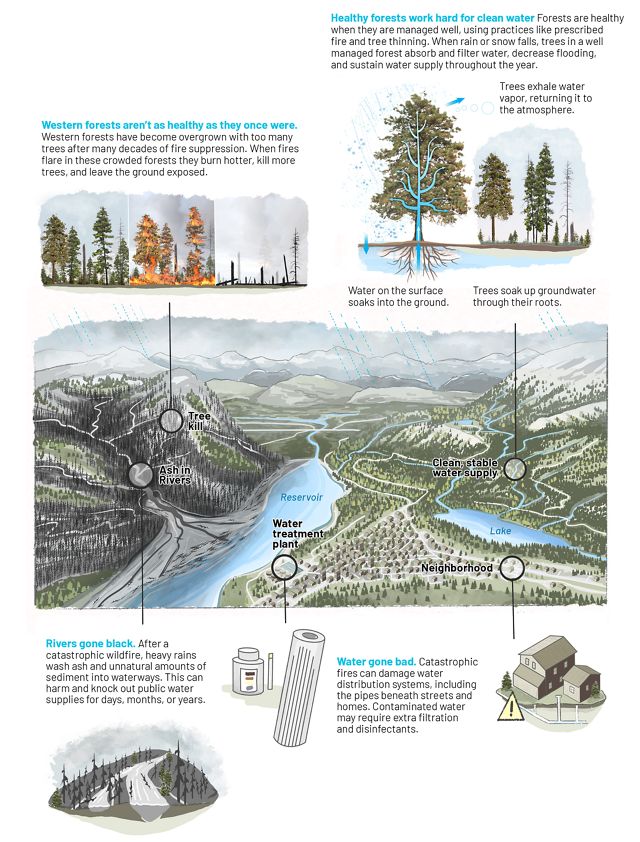

Forests give us water—and the healthiest forests do this best. When forests are healthy, they offer more for the birds and animals we love and they filter our water. But Western forests aren’t as healthy as they once were. That’s because something has been missing from a lot of our forests, and that something is fire.

For many decades, a widespread fear of wildfires led to a simple-minded line of attack all across the West: When a fire was spotted, firefighting crews were commonly sent to put out every new forest fire by ten o’clock the next morning. Reversing the mindset of the “10 a.m. rule” has taken many years, but bringing forests back in balance demands it: In Western forests, fire has a natural role. Forests are adapted to fire and people have traditionally worked with fire to renew wooded areas.

Without fire, odd as it may seem, forests that were historically more open and even sort of park-like become overgrown with too many trees. Now, when fires flare up in these crowded forests they burn hotter, kill more trees and leave the ground exposed. This sends ash and unnatural amounts of sediment into downstream waterways—and as towns and cities across the West know firsthand, they can do great harm and knock out water supplies for days, months or even years.

Fortunately, through long traditions of working with fire and a systematic process of experimentation and observation, fire practitioners have built a tremendous body of knowledge about how a natural fire cycle brings renewal to a forest. A natural low-intensity fire is like a reset switch for a forest—preventing out-of-control wildfires in the future.

Scientists have already identified the towns and cities all throughout the West where restoring nearby forests, with methods like setting prescribed fires intentionally and cutting a select number of trees to restore ecological balance, can keep sources of clean drinking water safe. What’s crucial now is time: Many forests have an unnatural build-up of woody fuels that are primed and ready to burn after fire’s long absence from the forest.

We know the clock is ticking. Today, we’re working with partners to restore Western forests in the United States and Canada. We pledge to do all we can, both on the ground and in policy, to bring balance back to even more forests and keep drinking water safe.

What this veteran firefighter sees—and hears—in the forest

It has everything to do with water.

Porfirio Chavarria has walked in forests all around the American West. He’s a firefighter in New Mexico who, for many years, went wherever he was called.

“I never said no when they would call me to go to a fire,” he says.

So his boots have led him to far-off places where there are no roads or even trails: through valleys with sparkling trout streams, high up mountain ridges and all manner of forests in between. He’s walked these forests in the days and weeks after a fire. And from what he sees—and hears—he knows some of these fires were not like the others.

Walking through the ashen remains of a fire that burned especially hot—“It just looks like the surface of the moon,” Chavarria says, thinking back—his footsteps can be so quiet he cannot hear them. Nothing crunches underfoot.

It’s not always like that after a forest fire. Sometimes, instead of ash and debris, the forest is still, well, a forest.

“Not everything is gone,” he says.

It can still look, feel and—yes, sound—like a forest.

“The sound of your feet walking through the forest crunches because you’re still walking on some of that duff layer that’s underneath,” he says, referring to the decaying needles, twigs and other plant debris that supply nutrients to plant life. “And you’re still seeing plenty of green trees throughout.”

These are signs saying the forest will be alright: Living trees will offer up pinecones bearing the seeds that can sprout into generations of new Ponderosa pine seedlings. The natural duff still there on the forest floor keeps soil in place. That matters when rains come because soil, if left barren, can erode away in flows of debris, fouling downstream waters.

Chavarria grew up downstream of mountain forests in the Indigenous community of Santa Clara Pueblo along the Rio Grande in northern New Mexico, and his culture’s generations upon generations of life here have shaped his understanding of water.

Quote: Porfirio Chavarria

In the Southwest, you understand water in a way that’s very distinct. Every drop is precious.

Water from the forest

The way fire affects forests that provide drinking water in many locales around the world is changing as temperatures on Earth continue to rise. In the West, the number of larger and hotter wildfires has more than doubled since the 1970s, and communities are feeling the effects.

For many towns, catastrophic wildfires pose tremendous risk to drinking water. The municipal water utility in the northern New Mexico town of Las Vegas, pop. 13,000, couldn’t provide clean water after the 2022 Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak fire. Months and years later, debris flows following seasonal monsoon rains wiped out the utility’s infrastructure. Rebuilding it is expected to cost at least $100 million. Airborne smoke can make it unsafe to breathe the outside air. And in some communities, neighborhoods and business districts that intermingle with undeveloped land can lie directly in the path of threatening wildfires—what fire experts call the wildland-urban interface.

Today, Chavarria draws on his years on the fire line to help communities prepare for the risk of fire. He works for the Santa Fe Fire Department to protect city water infrastructure from fire risk, and he has become a trusted advisor to homeowners who want to protect their neighborhoods in this capital city.

National forests reaching far up into the Sangre de Cristo Mountains around Santa Fe provide the city with 40% of its water supply, by way of two reservoirs. That’s not unusual. Nationwide, forests are an important source of drinking water for more than 150 million people.

The forests that offer the most reliable water supplies act as sponges, slowly releasing and filtering water to downstream waterways. In many locales, Western forests need to be restored back to full health if they’re to continue providing a reliable and safe supply of drinking water for downstream communities.

“The city has taken a huge interest in protecting that (water) resource and has made a lot of headway over the last 25 years in that respect,” he says.

Through the creation of the Rio Grande Water Fund, TNC has helped lead a diverse partnership committed to restoring forests in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado to protect sources of drinking water. Since 2014, the fund has raised more than $22 million in public and private investments to restore forests that supply water for towns and cities. Helping the forest in this way keeps clean water flowing to our taps.

For Chavarria, the health of the trees, the water and everything that makes up a forest are all connected.

“We want a healthy forest. We want clean water,” he says. “As you affect one, it affects everything else.”

TNC's Western Dry Forests and Fire Program

We're collaborating with partners across the West to develop cross-boundary solutions aimed at putting 50 million acres of forests in the U.S. and Canada on a trajectory to increased health and resilience by 2030—avoiding catastrophic wildfire and keeping clean water flowing. Learn more about the program.

Meet her favorite molecule

Then she’ll tell you how it gets to your faucet

For Jennifer Wellman, a TNC water scientist in Colorado, the best way to get to know a stream is to simply wade in and have a look around. She likes to slip into a pair of hip waders and walk right on in, testing her footing on the rocky cobbles as she goes.

“I look for certain indicators. You can tell a lot about a stream based on the aquatic insect community,” Jennifer says. “Just to kind of get a sense of what kind of fish food is available.”

She’ll flip over some rocks and take a close look. And in a healthy stream, Jennifer sees dragonflies, mayflies, damselflies, and more bugs in their early larval stages—she can name them all. For insects like these—food for trout—the underside of rocks is where life begins. For Jennifer, seeing them alive and well is an unmistakable sign of clean water for a living world.

Jennifer has a keen sense of how water flows downstream from point A to point B, and why we can’t have clean water if we don’t protect and care for the land in between. As a water scientist, she knows how we care for the forest and the land makes all the difference for our water—even if the nearest stream is miles away. Forests and healthy lands filter and store water as it percolates and flows downstream.

And where Jennifer lives and works, that means toward the Yampa River and eventually the mighty Colorado River.

Quote: Jennifer Wellman

Generally speaking, water originates as precipitation and high mountain streams in much smaller tributaries that flow from the upper parts of the watershed—the tippy tops of the mountains—down into the valleys.

And no matter where we live, a wonderful thing happens when we know where our water comes from.

“When we become more aware of our surrounding environment—not just our immediate neighborhood—we are more likely to protect it,” Jennifer says. “We can look to the forests as that great filter and wonderful sponge that holds water in place until it’s ready to flow downstream and be a part of our lives.”

And our bodies.

As a scientist, Jennifer gives quite a bit of thought to this most essential molecule—and the things that might be hitching a ride—such as natural minerals but sometimes, unfortunately, pollutants.

"It may not just be two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom,” she says.

In fact, Jennifer once served on a panel of water-tasting judges—not all that different from a wine tasting, with entrants competing for top honors. Moments like these—time for truly savoring the taste of a cup of water—have helped her think about where water comes from and why it tastes the way it does.

Water slurped from a healthy stream might have a particular taste. And on the other end of the spectrum, you might compare to what you’d taste in an accidental gulp of water while swimming in a chlorinated pool.

“You can sense the difference, right? You taste that level of chlorine and can feel it on your tongue.”

And the best water, the water that comes from healthy upstream forests where there are fewer pollution sources, simply requires less treatment and disinfection—saving costs and, quite likely, preserving its taste. She likes to help people understand what it takes for a community to protect their water.

She wants us to remember that when we know and respect the forest where our water comes from, we’re more likely to speak up on its behalf. Our neighbors can speak up, too. Above all, it comes down to this: Water is the source of all life. That’s why water is Jennifer’s favorite molecule.

This is how he fixes forests

The job takes grit—and a fire-resistant uniform

On the days when Matthew Ward goes out on a prescribed fire in a forest needing some help, he brings along a few things he can’t do without. A good pair of leather boots, for one. He has on his “yellows and greens,” too: The yellow fire-resistant shirt and olive-drab field pants donned by fire professionals as a precaution against close encounters with lapping flames. Always a hard hat and leather gloves.

“Those things go with you everywhere,” he says.

Same for the drip torch—the red metal can with a spout and a wick. It’ll hold about a half-gallon mix of gasoline and diesel, and has a single purpose: Tip it like a tea kettle and out come hot drips of fire.

“It can be very hot work and you end up choking in a fair amount of smoke,” Matthew says, his voice understated, the way of someone with years of life in the woods. “So it can be uncomfortable.”

But for Matthew, who got his start as a fire lookout in the Rocky Mountains and today oversees The Nature Conservancy’s forest and fire program in the state of Idaho, the work has got to be done. Today, in forest areas all across the West, in the United States and Canada, too many forests are out of balance and unhealthy. If there’s one single underlying reason, it’s this:

For a century or so, fires have been snuffed out.

“It really stems from the 1910 fires, when there were huge fires in the West, particularly in Idaho and Montana. And the Forest Service at that point made a decision. They wanted to try to keep fires out so they didn’t burn up valuable timber that would’ve been logged and gone to a local mill and helped the local economy.”

But that turnabout made forests into hotbeds for more dangerous catastrophic fire. The shorthand for forests like this? Tinderboxes.

“And we’re at a point now, due to a drying and warming climate, where we’re just seeing a lot bigger fires,” Matthew says.

They can turn so destructive that scientists came up with a new name for the biggest of them: Megafires. These big fires—100,000-plus acres—can get so hot they set forests back for years. They can bring on erosion and landslides.

It’s a disastrous mix for towns and cities that rely on healthy forests for a first level of natural filtration for their drinking water.

Quote: Matthew Ward

All that water that is just sinking through the forest floor is getting filtered and cleaned as it goes down into a stream and then further down into a community’s water system.

But major fire can harm the water supply, and even force water utilities to shut down.

Which is why TNC scientists have looked across the West and mapped out the forests where water supplies for towns and cities are in jeopardy from the looming threat of catastrophic fire. That knowledge is power—the rest is on-the-ground action.

As with any crisis, the playbook for fixing forests calls for everyone in the West to work together.

“It’s going to take a collective effort. We all have to come around to the sobering idea that we’re at a much more heightened risk than we were back in the 60s or 70s,” Matthew says. “The only way we’re going to get in front of this is to do restoration work.”

Prescribed fire can be the best tool for restoring forests and protecting water supplies. In another time and place, it may be best if workers with chainsaws clear smaller trees from overcrowded—and fire-prone—forests. Often, a combination of the two—both selective tree cutting and prescribed fire—offers the best fix.

Up close, working with flames just an arm’s length away, Matthew can see the good that prescribed fire brings. After less than a week, native grasses, like Idaho fescue and blue bunch wheat grass, are among the first signs of new life.

Signs of life

“You’re definitely going to see elk, they’re going to come in right away as soon as there’s green grass,” he says. “And you’re going to see a lot of bird life, particularly woodpeckers, keying into those burnt trees.”

Bushy Tailed: Removing overcrowded trees creates wildlife habitat by bringing light to the forest floor, which helps a diversity of plants thrive. © Mark Skalny 2024

Elk: These mammals return to the forests right away as soon as there’s green grass. © Steven David Johnson

Woodpecker: These birds are quick to return to forests, keying into burnt trees. © Karen Willes

Biodiversity: Countless plants and animals, big and small, depend on our forests across the West. © Charlie Hamilton James

The 150 million acres of forests across the West aren’t all the same, and Matthew wants people to know this: Not all fire is the same, either.

“It’s all fire, but the effect of one versus the other is really quite different. It’s two different things. Prescribed fire is a proactive management tool to drive towards your desired outcomes. A wildfire is an unplanned event and all you’re doing is reacting.

The challenge now, he says, is finding the balance between fire’s natural role in the forest and what must be controlled because of the harm it can bring to communities and to infrastructure like a safe and clean water supply.

Prescribed fires help to make wildfires less destructive. That’s good for the forest. It’s good for the safety of our towns and cities. And, because so much of our drinking water comes from forests, it’s good for all of us.

Why is this scientist devoting her working life to protecting this forest?

It’s where the water for her one million neighbors comes from.

In the ancient evergreen forest where Anna Buckley works, the ground squishes underfoot like a sponge. Moss seems to be draped over everything, even the trees themselves.

The job that brings her to this lush forest isn’t concerned with the trees themselves, majestic as they are. It’s the water—this forest is brimming with it. Anna works for the Portland Water Bureau, the public utility for Portland, Ore. And for more than a hundred years, most of the city's water has come from this forest.

Year in and year out, Anna’s purpose in this ever-verdant paradise remains the same.

Quote: Anna Buckley

My job is really to ensure that the watershed is protected for our drinking water supply.

And thanks to the forest’s yearly 11 feet of rain and sometimes snow, all of it carried in by westerly winds sweeping in from the Pacific Ocean, that water supply percolates, drips and flows from this forest of 300-foot-tall trees.

Of course, a forest is so much more than its trees—Anna likes to point to all it can do for the water people drink. Take the way it shades a stream.

“It keeps the water cold all the way to our intake and that’s important because warmer water actually breeds bacteria and viruses. And so by having colder water, that allows us to minimize the amount of chlorine that we have to add to the water to treat it.”

Pollution of any kind can harm a public water supply, but the single biggest risk to Portland’s water is the ash and sediment in the aftermath of a forest fire. Scientists know the last big fire here was in 1493, so most of the trees are 500 years old.

“We’ve known that fire is always a risk,” Anna says. “Going forward, looking at climate projections, we’re going to get longer, drier, hotter summers. That’s going to increase the risk for fire.”

Even here, in a rainforest of water-loving fir and hemlock and cedar where forest fires naturally occur less frequently than in drier forests in the West, rangers watch for smoke from a fire lookout. A sophisticated network of remote smoke-detecting cameras monitors the forest from the sky. And it’s not a place to see people out walking their dogs: This 100-square-mile area of forest surrounding the Bull Run River is off limits. That helps prevent wildfires, because data show that most fires, inadvertently and often through carelessness, are caused by people.

“There is a full-on suppression goal because we recognize that fire can have such an impact on water supply,” Anna says.

After a lightning storm in 2023, an area the size of 1,500 football fields burned in the upper reaches of Bull Run—since then, careful monitoring has shown it hasn’t left a measurable impact on water quality. Yet the concern remains.

If catastrophic fire does occur in Portland’s Bull Run water source, the city has ways of responding. Groundwater can fill some of the city’s water demand, and a new multibillion dollar water treatment plant is being designed to treat for a variety of pollutants, including the aftermath of a major forest fire.

Above all, as with many towns and cities, the best and first filter for Portland’s water remains a healthy forest.

“We like to think about the forest providing a clean, cold, constant supply of water,” Anna says. “The forest does a great job and all we have to do is protect it.”

The forests we depend on, depend on us

Continue learning about The Nature Conservancy's Western Dry Forest and Fire program.