Counting on Fish

New technology is revolutionizing how we track fish catches and yielding a treasure trove of data that is driving better management of fisheries.

Spring 2018

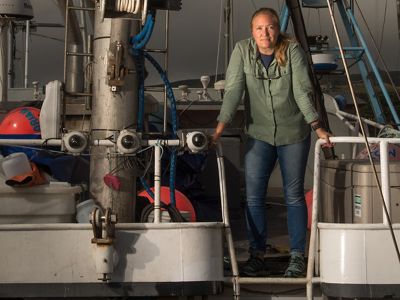

Centuries of fishing tradition weave through communities along the rugged Maine coastline. In the midcoast village of Port Clyde, at the tip of the St. George Peninsula, fourth-generation fisherman Randy Cushman has chased groundfish such as flounder, hake, sole, cod and pollock for 45 years—35 of them as captain and most on his 45-foot trawler, the Ella Christine.

During that time, Cushman has seen the size and type of fish in these waters change, along with the rules about what he could catch. At the Portland Fish Exchange, where Cushman sells his catch, in 2016 the number of landings—fish brought into port and sold—were roughly 12 percent of 2003 levels, a drop largely attributable to decreases of up to 90 percent between 2010 and 2016 in how much cod Gulf of Maine fishers were allowed to pull in.

Fisheries managers across the country set these catch limits in tune with the rise and fall of the number of fish in the sea. Estimates on how many of the world’s fisheries are struggling vary in part because of a lack of data, but the data that does exist suggests that many fisheries are overfished or in decline. Balancing viable commercial fisheries with the health of specific species and the wider ocean ecosystem presents a growing challenge. It requires estimating how many fish are in the ocean and how many of them fishers can catch this year to have similar or better populations next year—questions that are “somewhere between wicked hard and impossible,” says Chris McGuire, a marine policy expert who directs the Massachusetts Marine Program for The Nature Conservancy. Current methods oversimplify, he says, and basically result in a snapshot in time that can’t account for all the variables.

So researchers, managers, marine conservationists and fishermen like Cushman have teamed up to find better ways to count fish, in New England waters and beyond. While industry regulators have relied on human observers on boats to verify a captain’s reported catch, a growing wave of fisheries are floating the idea of using technology instead.Electronic monitoring, essentially video cameras on boats, may provide more accurate, cost-effective and timely fish counts, making it possible to hook catch limits more closely to actual populations and improving the effectiveness of conservation restrictions.

“Everyone complains that what fishermen observe on the water doesn’t match the science,” McGuire says. “But you have to have good information going into the models to get good science out.”

The Hunt For Data

To put it another way, you cannot manage what you cannot measure, says Mark Zimring, the director of a TNC program focused on Indo-Pacific tuna. And getting those measurements accurate is a challenge.

Currently, U.S. fisheries rely largely on catch limits, with quotas based on estimates of the size of fish populations. Catch limits are only the latest fishery management tool in a long history of sometimes stormy negotiations between fishers and regulators. Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, the fortunes of fishing communities and the health of marine ecosystems often followed the booms and crashes of fish populations, the changing equipment available to fishers and the level of competition from abroad. In the 1970s, a landmark piece of marine legislation, the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, established stronger U.S. jurisdiction over coastal waters, charging eight regional fishery management councils with developing sustainable management plans based on science. The debates over how many fish were in the sea heated up.

By 2011, all U.S. fisheries managers had set catch limitsbased on assessments of fish populations. Some had set the limits several years earlier. These assessments are based on data collected on trawl surveys conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service and reports from fishers. Fishers are required to report everything that comes over the rail of a boat: landings and discards (fish thrown overboard because they’re the wrong species or outside legal limits).

But that information is incomplete, and, from fishers’ perspectives, out of date by the time it’s used. When fishers observe increases in a stock, official data backing that up can take two or three years to reach managers, says Chris Brown, president of Seafood Harvesters of America and a fishing boat captain in Rhode Island. “We don’t have any opportunity to catch them while numbers are up. Then we’re gifted the opportunity to increase pressure on a fishery right at the time it can’t take it. We’re always out of sync.”

Fishers and regulators needed a way to get in sync, but the common practice of using human monitors on boats not only brought its own problems but also provided inadequate data in some regions.

Experimenting With Cameras on Boats

By the mid-2000s, with video cameras increasingly common in a multitude of settings, a number of fisheries began to test using these cameras to provide information on catch and discards for population assessments. Fisheries program staff at TNC thought the idea showed promise and decided to help accelerate its implementation in the United States.

In 2013, TNC partnered with the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association, Gulf of Maine Research Institute and Ecotrust Canada to install camera systems on two vessels and another five the following year, including Cushman’s Ella Christine. The cameras collected video of an individual boat’s catch and of each fish discarded back to the sea. Then a reviewer on land used the video to tally the total catch. The partners paid the cost of equipment and reviewing the footage.

The three-year pilot project showed that data generated by video reviewers analyzing footage was comparable to that from observers on the boats. The National Marine Fisheries Service approved a special permit for the 2016 season allowing video monitoring as a replacement for at-sea monitoring on certain boats, and in 2017, McGuire reports, 17 vessels in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Rhode Island carried cameras.

Every fishery has unique characteristics, so in 2014, TNC launched testing on the West Coast of the United States, partnering with the Environmental Defense Fund and the California Groundfish Collective. That fishery’s management council requires every trip to have a human observer on board to verify discards as well as individuals on shore checking the catch.

Data from six vessels off the California coast also showed no significant difference between traditional logbook estimates and records from reviewing onboard camera videos. Fishers saw some other differences, though: They found that cameras were significantly cheaper and allowed them to fish when they—and the weather—were ready, rather than having to wait and pay for a human observer. Cameras also took up less boat space; California fisherman Geoff Bettencourt was able to sleep in his own bunk again after surrendering it to an observer for four years. In April 2017, the Pacific Fishery Management Council recommended regulations to allow for electronic monitoring in the West Coast Groundfish fishery by 2018 or 2019, depending on the gear involved.

With the basic technology proven, TNC now hopes to improve it, says Kate Kauer, TNC’s California groundfish program director. That includes tweaking the placement of cameras, developing algorithms to do some of the work of human reviewers and testing video upload via satellite rather than on mailed-in hard drives. Outside the lab, TNC marine program managers are helping to inform policies for the use of electronic monitoring as well as encouraging others to buy into the concept.

But the bottom line is the accuracy of the data. Accurate, timely data on fish populations, size of catch and amount of bycatch—unintended species caught while trying to catch something else—will help managers set appropriate catch limits and guide use of other management and conservation tools, such as closures or gear modification. Better data, in short, supports better management. For example, before catch limits and 100 percent monitoring in California, the groundfish fishery had been declared a disaster, with many stocks considered depleted or overfished. But a lot of fishers didn’t think it was that bad, TNC’s McGuire says.

“Now, we have some really good data and startling reports of rebuilding,” he says. Several fish stocks have grown faster than researchers thought biologically possible, he says. “We don’t hear fishermen complaining about bad assessments. It’s an interesting lesson on the value of good data.”

It also includes fishers in the science and management process in a way not often done before, says Geoffrey Smith, TNC’s Gulf of Maine marine program director. “It empowers fishermen to be a part of the process instead of a victim of it,” he says. And the evidence of the potential of electronic monitoring to reduce costs without compromising data quality or integrity represents a “game changer” farther afield.

TNC wants to apply these concepts in the western and central Pacific tuna fishery, which drops 1 billion hooks a year and has 2 percent human observer coverage. Cameras are being installed aboard 26 boats that fish in waters managed by the Parties to the Nauru Agreement. The group’s members are Micronesia, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Tuvalu. Together, they control 70 percent of the area’s tuna fishery. Data from the cameras can help guide the group’s management decisions, such as capping bycatch—which accounts for as much as a third of what these vessels bring in—rather than restricting when and where boats can fish, says Mark Zimring.

“Once a boat hits the number of sharks allowed, for example, they are on the dock,” Zimring says. “That creates a powerful incentive for them to solve the problem, to not catch things we don’t want them to catch. It partners us with fishers.”

A New Tide

In June 2015, the Highly Migratory Species fishery in the Atlantic became the first in the U.S. to officially transition to cameras as electronic monitors. Cameras are used in its management program for deepwater migratory fish, which includes tuna, swordfish, sharks and billfish. California’s groundfishery will likely be next, in 2018 and 2019. In the meantime, the Magnuson-Stevens Act, most recently renewed in 2006, is up for reauthorization.

It may take longer for New England to make the switch. On the West Coast, fishers pay to have an observer on the boat each trip, making any cheaper option an appealing one. New England’s fishery requires observers on only about 15 percent of trips, says Smith. As a result, the cost-effectiveness isn’t as strong of an incentive there.

Having cameras on board also makes some uneasy; more than one fisher has likened it to Big Brother. At the same time, in an industry that hinges on how many fish officials say there are in the sea, the prospect of getting better numbers, and faster, may persuade some fishers to consider cameras.

For others, accountability offers incentive enough.

“I have nothing to hide and plenty to prove,” Cushman says. “When the science says one thing and fishermen see another, the camera keeps everyone honest.”