Description

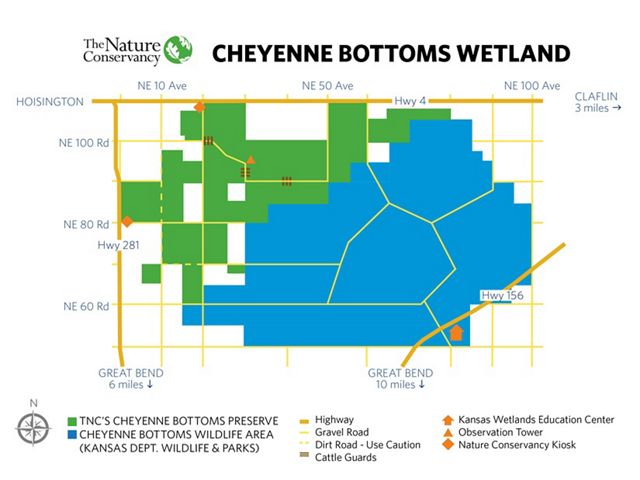

Cheyenne Bottoms is a 41,000-acre wetland complex in central Kansas and one of the top staging areas (the places migrating birds stop to feed and rest) for shorebirds and waterfowl in the United States. These wetlands host tens of thousands of shorebirds and up to a quarter million waterfowl each year during their migrations. Cheyenne Bottoms is one of only 34 sites in the United States designated a “Wetland of International Importance” by the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands.

The Nature Conservancy owns and manages the 8,018-acre Cheyenne Bottoms Preserve adjacent to the 19,857-acre Cheyenne Bottoms Wildlife Area, which is managed by the Kansas Department of Wildlife & Parks. Ducks Unlimited is also a key partner that is protecting waterfowl and shorebird habitat at Cheyenne Bottoms.