Ghost sightings are becoming increasingly common in southwest Florida. Sometimes hunters’ remote camera traps will catch grainy grayish images at night. The subjects’ eyes have a spectral glow from the reflection of the camera’s infrared light. Live daytime sightings are usually brief: a quick glimpse before the ethereal figure vanishes into the dense underbrush of palmettos.

These ghosts—endangered Florida panthers—are real. That they exist at all is a near miracle, as the large cats almost vanished in the 1970s, when scientists estimated there were maybe 20 Florida panthers still surviving in the wild. With intensive human intervention, the panther population is estimated to have grown tenfold over the past 40 years, but they are still extremely rare animals.

Cliff Coleman regularly finds evidence of panthers passing through Black Boar Ranch, an 1,800-acre private hunting property he manages in the interior of southwestern Florida near the city of LaBelle. Last year, Coleman was clearing debris from a hurricane when he discovered fresh signs of a male panther. A leaning palm tree’s trunk was shredded like a gigantic cat’s scratching post, and next to it, pine needles were wadded into softball-sized mounds on the ground. “The males will bunch up the pine needles and then urinate on them to mark their scent here,” he says. It’s a warning sign to other males in the area and a welcome mat to potential mates.

The panthers don’t stay long on the ranch, says Coleman. They easily hop the 8-foot-tall fences, kill some game in the hunting preserve, eat and then disappear. The males each roam overlapping territories of about 200 square miles. When two meet, they will fight—often until one is dead. Females stay closer to their birthplaces, roaming about 50 square miles.

That’s a lot of territory to keep relatively wild in a state where 900 new residents arrive every day. With so many people streaming in, says Wendy Mathews, TNC’s conservation projects manager for Florida, development is starting to push inland. Farms, ranches and forests that the panthers and other wildlife need are being turned into neighborhoods and roads.

If they are ever going to recover, Florida panthers will need more protected habitat, and plenty of it. To get the Florida panther off the federal Endangered Species List, the state and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) must help the animals reestablish three independent breeding populations, each consisting of 240 cats.

That’s why TNC worked with the Natural Resources Conservation Service to buy a conservation easement on the Black Boar Ranch in 2015, as well as on the next two properties to the north. It’s part of a decades-long collaboration among government agencies and nonprofit groups to preserve a contiguous swath of undeveloped land—a conservation corridor—so the animals can expand their range and increase their numbers.

The Disappearing Florida Panther

The Florida panther is a subspecies of the American puma—known as mountain lion or cougar in other parts of the country—that used to range from Canada to the Andes Mountains. But after European settlers arrived, the big cats were hunted to protect livestock and their skins were sold in the fur trade.

By the time the Endangered Species Act became law in 1973, pumas had been almost completely removed from the eastern United States. The few survivors were Florida panthers that held on by living in the Big Cypress region of South Florida, west of the Everglades. It was the one place where the enigmatic animals could retreat from humans.

The Florida panther became one of the first animals put on the federal Endangered Species List. The listing pushed the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and FWS to restore the population.

Early efforts started in the 1970s with tagging and collecting blood samples from the remaining Florida panthers. Later, radio collars were used to track their movements. Biologists started investigating sightings and panther deaths. By the time Darrell Land began working for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission as a panther researcher in 1985, scientists were starting to understand two important facts about these animals: Each Florida panther roamed an extremely large range, and the population’s gene pool had become dangerously shallow.

Some genetic studies suggest that the population may have dipped down to just three females. By the mid-1980s, Land says the population estimates were hanging around 20 to 30 animals in the wild. Many were the product of inbreeding, and some males were incapable of reproducing. In 1995, eight female pumas from Texas were outfitted with radio collars and temporarily released (they were later recaptured) into southwest Florida to mimic the historic gene flow between the various subspecies.

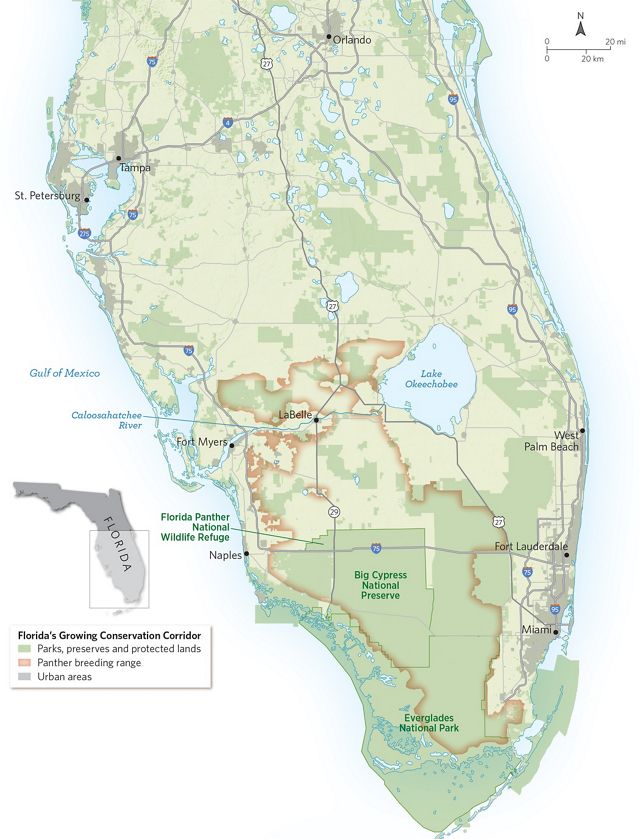

The efforts paid off. By 2007, the number of Florida panthers climbed to roughly 100, according to the FWS, and today’s number is twice that. Florida panthers have begun expanding their range well beyond the Everglades. Researchers mostly measure the species’ functional area by tracking where the breeding females live. (“A male can go off … and disappear into the landscape, but he isn’t going to produce any kittens [on his own],” notes Land.) Year after year, the female panthers keep pushing the species’ breeding range farther up the map.

“We’re seeing them repopulate in places where they used to live before,” says Land. He can pull up maps on his computer that pinpoint every reported Florida panther sighting since the 1970s, as well as reported deaths; incidents when panthers killed pets or livestock; and records of reported births. Taken together, these maps tell a story of the animals gradually moving out of the parks and wildlife management zones near the Everglades and encountering their human neighbors.

“When we started this, we thought they needed land that was far removed from people,” says Land. But the Florida panther’s adaptability has impressed him. They survive and hunt in forests, industrial-scale farms and even venture into neighborhoods. “That’s where we are now. We’re watching these human-and-panther interactions and learning how to manage those situations.”

Those interactions often don’t end well for the panthers. In 2018, 30 panthers were reported dead. Twenty-six of them were hit by vehicles.

Where Can Panthers Go?

As the Florida panther population grows, many of the cats have roamed west only to die as they try to live amid the busy roads around the city of Naples. The animals fare better when they move north through undeveloped land. But what used to be mostly cattle farms, groves and wild land in the 1970s is changing over to rural subdivisions, retirement communities and RV parks.

During Florida’s real estate boom in the early 2000s, land was selling fast. The state, the FWS, and independent conservation groups started looking strategically at the landscape and identifying which tracts of land—if protected—could provide contiguous habitats that favor the Florida panther.

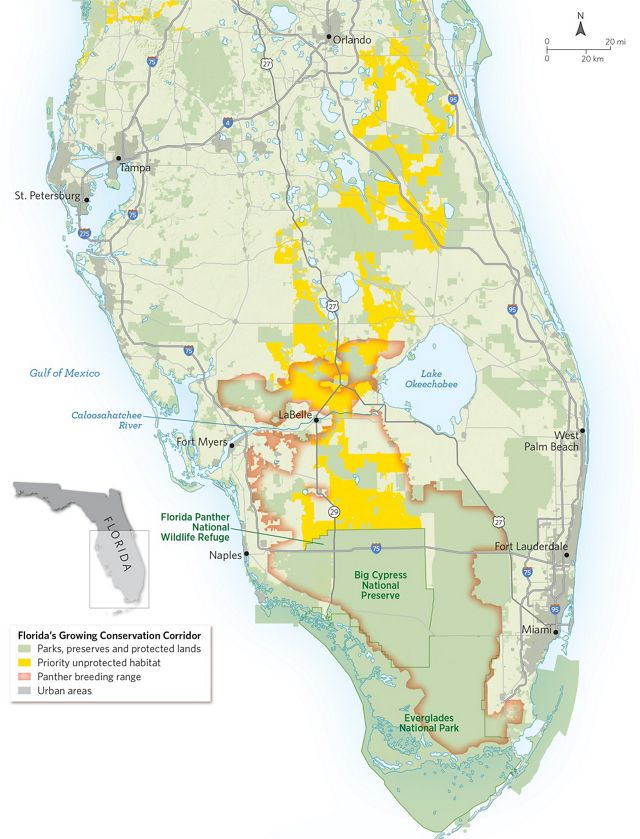

On the map, a conservation corridor started to take shape. It looks like an upside-down funnel between Big Cypress Wildlife Refuge (located just northwest of the Everglades) and the Caloosahatchee River to the north, which is part of a waterway that connects Lake Okeechobee and the Gulf of America. The landscape is a mix of protected and state-managed lands and private working lands that are sparsely populated, all divided by a few main highways.

At the tip of the funnel, the Caloosahatchee River became an unofficial goal line for conservationists. To the north sit large tracts of private ranchlands as well as many protected areas south of metro Orlando—a veritable promised land of potential panther habitat. But no female panthers had been spotted beyond the river since the 1970s. It was clear to conservationists that they would have to protect both sides of the river from development so panthers would always have a protected place to cross.

But in the mid-2000s, a 1,200-acre ranch that sits between the Black Boar Ranch hunting lodge and the Caloosahatchee River was purchased by American Prime, a development company that had plans to turn the ranch into a large waterfront neighborhood. It would put homes, streets and people directly in the path of the panther corridor. Then the Great Recession of 2008 put a temporary halt to Florida’s real estate boom before the developer started work. Word got out that the property was facing foreclosure, and TNC staff in Florida quickly rallied to try to gather enough funds to buy the land and keep it as a ranch.

“I’m a biologist, not a Realtor,” Mathews says. “But we figured it out.”

In late 2012, with funding from the FWS (passed through the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission), the U.S. Department of Agriculture and several state agencies in hand, Mathews and several other TNC staffers finalized the land’s purchase—just one day before the property was set to be auctioned on the Glades County courthouse steps. They had pre-negotiated the property’s resale to a local rancher, who agreed to buy the property with conservation easements. These easements prevent future development on the land, and the property must remain as a ranch or some other type of low-intensity agricultural producer.

For conservationists, it was a huge victory. “The day we closed on the property was this huge release of tension and pure excitement,” says Mathews.

By this time, Coleman was seeing regular evidence of Florida panthers at the hunting lodge just to the south. Mathews says that everyone knew it was just a matter of time before a female panther crossed the Caloosahatchee River.

Finally, in early 2016, camera traps confirmed the predictions: For the first time in more than 40 years, a female Florida panther was spotted leading her kittens north of the Caloosahatchee. To people like Land and David Shindle—panther leader for the FWS—who have guided the animal’s progress for decades, the discovery was equally miraculous and inevitable.

Prioritizing the Panther

Since that big win in 2012, TNC has bought Conservation easements on the Black Boar hunting preserve and an orange grove on the north side of the Caloosahatchee. And the Florida Department of Transportation has built an animal underpass beneath the busy highway that separates Black Boar and another ranch on the south banks of the Caloosahatchee. A 12-foot-tall chain-link fence runs for less than a mile down both sides of the highway to direct panthers and other wild animals toward the underpass and away from the road. There, wet sand shows paw prints of all the animals that crossed from the hunting preserve to the ranch since the last rain: deer, boar, raccoons, possums, bobcat, black bears, panthers and many more.

These days, Mathews says, TNC is trying to buy more easements on strategically important properties that will build up the conservation corridor, especially parcels that are on opposite sides of a highway from already-protected properties. “When both sides of the highway are protected, we can make a case to the Florida DOT to spend the money to build an underpass in that location,” she says. The underpasses are becoming a more common sight in southwest Florida—a visible sign that Floridians are learning how to live with their native panther.

How did we get these camera trap photos?

Photographer Carlton Ward Jr. explains how he did it.

On the HuntBut that doesn’t mean the Florida panther is in the clear. Both Land and Shindle are getting more calls from people who have lost livestock to Florida panthers. A recent federal Farm Bill allows livestock owners to be repaid for animals killed by a protected species, but Shindle admits that the process puts a heavy burden of proof on the owners (panthers drag their kills away to be eaten, often leaving ranchers with no evidence to seek repayment).

Also, people are still moving to Florida, and just this year the state legislature passed a bill ordering its department of transportation to investigate the feasibility of building new toll roads in the state’s interior. Plans include one highway that would run between the Naples area and Orlando, slicing through the part of the state that has been so crucial to the panther’s recovery so far.

From the time the bill was announced, Mathews says, TNC was pressing state officials to consult with environmentalists to consider the roads’ effects on endangered wildlife. She will serve with representatives of three other environmental organizations on a task force that will help evaluate the effects of road construction on panther and wildlife habitat. Part of the task force’s work will be to host a series of public meetings for residents of all the counties to voice their opinions on how the proposed toll roads will affect their lives and the wilderness.

Mathews says that the initial disaster would be that the toll road severs critical habitat and puts panthers in the way of more speeding cars. But also those toll roads will come with exit ramps that will push development even farther into Florida panther habitat.

“The ultimate win would be the removal of the Southwest-Central Florida Connector from consideration in the toll road planning process,” says Mathews. She has seen other major road projects tabled before. The next-best win would be to see the road “sited such that the least amount of currently undeveloped lands are impacted.”

Florida has a history for approving development first and dealing with the consequences later, but Mathews notes how much money the state has put into conservation since the 1990s through its Florida Forever program. In recent years state conservation funding has been harder to come by, she says, but public interest in protecting Florida’s wildlife still runs strong. “I would say, mostly, public opinion sees the panther as important and worth saving.”

And by protecting this remarkable ghost cat, Floridians may still save their wild lands.