Closing the Gap

We can stop the extinction crisis, but we have to fully fund conservation first.

Summer 2021

Considering the long arc of human inquiry, the concept of biodiversity is relatively new. Charles Darwin laid the foundation when he expounded on natural selection and devised the evolutionary tree of life in the mid-19th century—yet biodiversity only joined the scientific lexicon as a well-developed concept in the 1980s. Recently though, the loss of biodiversity has accelerated. From 1970 to 2016 there was a nearly 70% average decline in populations of birds, amphibians, mammals, fish and reptiles. And by the year 2070, research suggests, the Earth could lose a third or more of its species if steps aren’t taken now to stop it. Many threatened species are the plants, insects, birds, microorganisms and marine life that underpin human survival.

That’s why scientists, conservationists and global visionaries have issued an urgent call to preserve the planet’s biodiversity, and financial expert Henry M. Paulson Jr. is among them. Doing so is possible, he insists, if governments and the private sector combine efforts to transform how economies work—to insert sustainability into the everyday business of the world.

Mind the Gap, Then Fix It

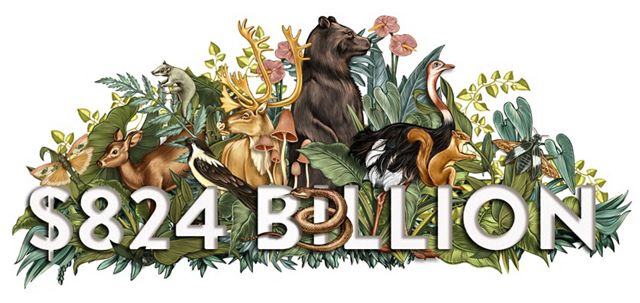

The biodiversity crisis grows more urgent by the day. Transforming government policy and finance can unleash tremendous new investment for nature, stemming the loss of species and sparing nature from further harm. In 2019, the annual investment in nature tallied up to between $124 billion and $143 billion. A new study calls for boosting that investment to between $722 billion and $967 billion—meaning we need to fill a shortfall of $598 billion to $824 billion.

Paulson brings a finance perspective to the question of how to save biodiversity. He was raised on a small farm in Illinois, where he grew to love nature. But he’s more commonly known as a former CEO of the investment bank Goldman Sachs and the former U.S. Treasury Secretary who helped stabilize the American economy after the financial crisis of 2008. He served as a member of The Nature Conservancy’s global board of directors and, more recently, he has led the Paulson Institute, a “think-and-do tank” with the goal of building a more sustainable world and fostering healthier ties between the U.S. and Chinese economies.

Now, Paulson is leading a collaborative effort to challenge governments, business and the finance sector to entirely reassess how humanity values nature—and harness economic forces to nurture biodiversity.

3 Ways to Fix the Finance Gap

Spending can target different elements that affect the biodiversity crisis

A recent report published by the Paulson Institute, Cornell University and The Nature Conservancy offers the world a road map for finding ways to pay for conservation. The report, Financing Nature: Closing the Biodiversity Financing Gap, says that the global economy directs an average of between $124 billion and $143 billion annually to biodiversity funding. This includes governmental investment in sustainable agriculture and forestry and the collective efforts of the world’s philanthropic initiatives for nature. The report reviews how spending can support biodiversity, but the big takeaway is this: There’s a tremendous funding gap between current investment and the level necessary to maintain biodiversity. In fact, the research shows the world needs to close the annual financing gap of as much as $824 billion by 2030.

Paulson spoke with Nature Conservancy magazine to discuss how enacting government policy and creating incentives to shift private investment toward sustainability could close that biodiversity funding gap.

Spending for Survival

You’re committed to making the economic case for sustaining the planet’s biodiversity. You’re also known for speaking up for the environment’s intrinsic value. How do you balance these two perspectives?

I don’t see these as competing perspectives. Nature has intrinsic value, of course. It is the greatest source of beauty, inspiration, innovation and intellectual interest—indeed of everything that is good about life. But our political and economic systems often consider nature’s benefits “free.” This means that conserving the environment is not adequately rewarded financially, and damaging it is not appropriately penalized. If we want to preserve and protect the world’s biodiversity, this needs to change.

How do you help others understand the global biodiversity crisis, and how do you convey a sense of urgency?

Well, I start with the simple fact that we’re living through one of the most dramatic extinction episodes in our planet’s history. We’re losing 1,000 times the natural rate of one to five species per year. This is not the kind of world we should resign ourselves

to leave for our children and grandchildren.

What More Money for Biodiversity Will Change

The recent Financing Nature report sets global dollar figures for future conservation goals. Here are several improvements we could see:

-

Increased Land and Marine Protections

To fend off biodiversity loss, critical habitats need to be protected. The Financing Nature report’s proposed global goal is to protect 30% of Earth’s lands and marine waters by 2030.

-

Healthier Forest Management

Existing forests should be sustainably managed—and lost forests restored—to balance timber production with the protection of biodiversity and maintenance of ecosystem integrity.

-

Agriculture and Fishing Industries That Cause Less Harm

Financial support should be given to practices that protect biodiversity while still ensuring the productive harvests needed to feed the world, both on land and in the ocean.

-

Cities That Create Less Water Pollution

Better infrastructure can reduce cities’ footprints on the landscape. This means investing in improved utilities and stormwater management systems, and protecting sources of clean water.

You’ve said that biodiversity loss means more than losing plants and animals. Can you explain?

That’s right. Biodiversity loss isn’t just an issue for environmentalists—it poses a fundamental risk to human well-being. It affects our food supply, our economic and physical health, and the beauty of our natural world. One example: The worldwide loss of pollinators—butterflies, bees, moths and other insects—would lead to an estimated drop in annual agricultural output of around $217 billion.

But we’re not locked into this path of biodiversity loss. We can make a change, right?

I don’t believe anything is inevitable when it comes to biodiversity loss. Our choices and policies can and do make a difference. In our report, we offer a pragmatic path forward, with key policies and financing mechanisms necessary to arrest the alarming decline in global biodiversity.

In that report you estimate it will take an additional $598 billion to $824 billion annually. How do we make these investments in biodiversity in a world reeling from the pandemic, poverty and other problems?

Right now, we have governments committing to spend trillions of dollars to jump-start and rebuild their economies in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. And so, while there is significant short-term pressure to counter this economic shock, as well as the other problems you mention, there is also enormous opportunity to think long-term about how resources can be redirected to projects and initiatives that will not only create jobs and kick-start economies, but also protect nature in a way that reduces the prospect of future pandemics and other disasters.

Quote: Henry Paulson

It’s far cheaper to prevent environmental damage than to clean it up afterward.

Can you give an example of specific kinds of investments and financial flows that can be shifted to help, rather than harm, biodiversity?

Sure. One recommendation we highlight in our report is investment in natural “green” infrastructure. In the 1990s, New York City, for example, improved the ability of the Catskills watershed [upstream from the city] to filter the city’s water. They paid farmers not to use chemical products such as fertilizer, herbicides and pesticides, and to move animals away from streams. They helped improve sewage systems and established conservation agreements. The result was cleaner water achieved with an investment of around $1.5 billion, compared with $8 billion needed to build a filtration plant.

In that example and others, the idea is to generate corporate investment in nature, right? You’re not talking about corporate philanthropy here. Can you explain the difference?

It’s a crucial distinction. Philanthropy is a way to distribute profits. Investing is a way that the private sector generates profit. Deliberately investing at a loss isn’t a realistic business model, so while many business leaders may want to protect nature, they won’t deploy capital for conservation or environmental projects that don’t promise economic returns. And so, to realize the potential of private sector investment in nature protection and conservation, governments must put in place policy measures that induce the private

sector to invest.

The right policies can help to incentivize investment for the public good. How would such a shift proceed in a way that is fair and equitable?

Let’s first acknowledge that it’s the poorest countries and the poorest people who are least equipped to deal with—and will ultimately suffer most from—the effects of biodiversity loss. And second, let’s be clear that current policies that harm biodiversity are far from fair and equitable. … Subsidies intended to support economic development can have unintended results that exacerbate the condition of disadvantaged groups. So, as we design policies to protect biodiversity, we need to be conscious of their distributional impacts.

As a global finance leader, a former treasury secretary and former head of Goldman Sachs, your views carry a lot of weight. What would you say to folks who might reflexively hesitate to connect finance to biodiversity?

Any business leader should understand the importance of accurately factoring risk into decision-making. Simply put, this mindset, and the tools of business and finance, need to be applied to the question of biodiversity loss. The fact is, it’s far cheaper to prevent environmental damage than to clean it up afterward. And given the economic risks of biodiversity loss that we document in our report, it’s clear that waiting to act—or failing to act—isn’t being prudent; it’s radical risk taking.

What role can supporters of The Nature Conservancy play in fixing the biodiversity funding gap?

There are plenty of ways to help, and if you’re a supporter of The Nature Conservancy, you’re likely already ahead of the curve. From my vantage point, it’s the national responses—the legislation, policies and regulations—that are necessary for bridging the biodiversity funding gap. And so, advocacy and engagement are key. It’s critical to advocate for nature, arm yourself with a compelling economic case and hold your governments to account for protecting biodiversity.

How hopeful are you that the world can achieve this level of change in such a relatively short span of time?

It’s going to be an uphill climb, but there are a number of optimistic signs. Today, there’s a new sense of urgency around nature conservation issues. There’s a rapidly growing interest in the field of green and sustainable finance. And most importantly, there’s a renewed sense that collective effort can make a difference, especially from young people. I’m hopeful that the combined effect of these trends is that investing in nature will move into the mainstream of the financial world soon enough to arrest the alarming decline of our biodiversity.

Get the Magazine

Become a member of The Nature Conservancy and you'll receive the quarterly print magazine

Subscribe now