Capturing the Human Planet

How viewing the world from above turned an aerial photographer into an “accidental environmentalist.”

Summer 2020

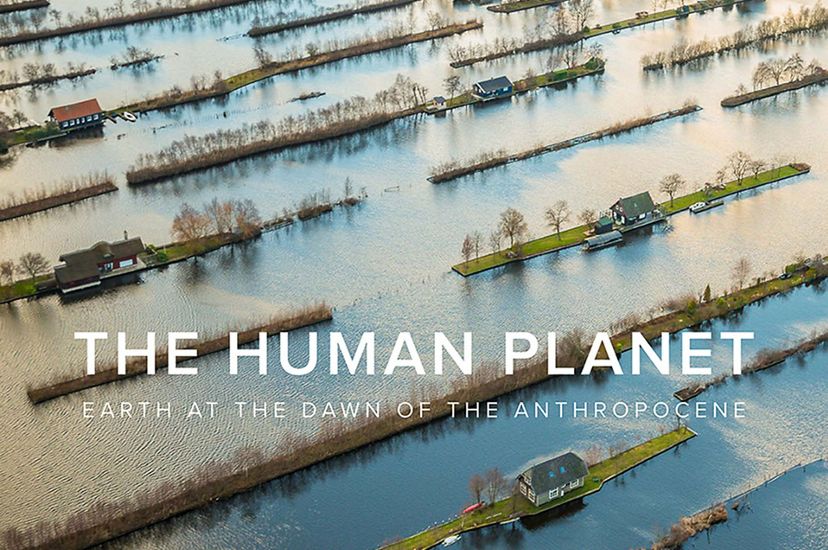

Scientists first proposed the term “Anthropocene” in the 1980s to describe a new epoch of geological time defined by the impact of humans on the world. Though the term has sparked much debate, aerial photographer George Steinmetz’s new book, The Human Planet: Earth at the Dawn of the Anthropocene, leaves little doubt that our footprint on the Earth is profound and vast.

“The cumulative effect [of the photos] is you look at the Earth and you see everything from New York City to people in New Guinea and the whole spectrum of humanity on this planet and you realize how that all fits together,” says Steinmetz. “It’s pretty astounding … the feeling you get when you realize that we’re custodians of this place.”

Steinmetz has traveled to dozens of countries in his nearly four-decade career photographing stories for National Geographic and other magazines. From above, usually in paragliders and helicopters, he’s watched as people have reshaped the world beneath his lens. His new book, he says, is “intended to be both a celebration of the Earth and kind of a cautionary tale at the same time.”

“I found a lot of places where we’re kind of not being the most careful custodians and I think we need to be more careful,” he says. “We have to be better custodians of our little blue marble.”

Interview with George Steinmetz

Nature Conservancy: You’ve spent much of your career covering stories from the ground, but for the last 20 years you’ve focused on photographing from helicopters, drones and paragliders. Why the shift to aerial photography?

Steinmetz: I dropped out of college [in the 1970s]. I was studying geology and geophysics [at Stanford] and I went on a yearlong hitchhiking trip across the Sahara and I had this idea: Wouldn’t it be amazing if I could see that landscape from above? In a car, I felt like I was an ant crawling across the carpet. I thought, if I could get up ... I didn’t want to be in a satellite, but if I could be bird height I could really understand and explore and decode that landscape.

That idea stayed with me. So once I was working for magazines and I was able to talk people into paying for that kind of thing, that’s what I did.

Quote: George Steinmetz

I had this idea: Wouldn't it be amazing if I could see the landscape from above? If I could be bird height, I could really see and explore and decode it."

What makes aerial photography different?

From the air, you can understand the forces that shape the landscape, whether those are human or natural. Like in the Sahara you can see the ancient river courses. You can see ancient camel tracks. You can see signs of farming that took place there thousands of years ago.

It’s like you get a sense of time up there?

Yeah. Like in the Namib desert [of Namibia, Angola and South Africa], which is a very sterile environment, you can see cart tracks that are like a couple hundred years old‚ if you go up there really early in the morning when the light’s really low and the shadows illuminate that stuff. Aerial observation—it’s really an unbeatable platform.

A Bird's Eye View

How does aerial photography help you convey your theme for the book: humanity’s impact on the planet?

Between, like, 100 to 500 feet, you can see the world kind of more three-dimensionally. You can see if it’s a goat or a camel, or is it a Toyota, or is it a Land Rover? So you can see things at a human scale, but you can also see the vastness of the landscape. From up above, you can really see land-use issues.

Like what? Well, I find the scale of food production quite interesting. I try to seek out the largest-scale enterprises I can, like the biggest shrimp farm in the world, or the biggest cattle feed lot. When you see things at that scale, it’s really quite staggering.

You also see the ingenuity of humanity, like how we’ve been able to manipulate animals and the land or biology to produce food. It’s really an ingenious machine. I find it particularly interesting to see how humanity has shaped the Earth, for good or for bad.

How so? I mean in Africa, particularly, you see a lot of ways different cultures have adapted themselves to the land, like where they decide to put their cattle camps and their villages. Or in the Middle East they’ll put villages on the hilltops. They don’t take up the farmland.

You see how people have learned to adapt themselves to the landscape, and then you come to the industrialized world, and how we’ve come in with technology and just plowed it and dammed it and manipulated it. Is it man versus nature, or man with nature? You see very different approaches.

Quote: George Steinmetz

I find it particularly interesting to see how humanity has shaped the Earth, for good or for bad.

You say in the book that you’re an accidental environmentalist.

Yeah, I’m kind of shy about that term. I feel like I’ve come to [it]. It wasn’t my intention, but you just see the beauty of the natural world and how we continue to chew away at it. It’s quite disturbing.

I think that’s part of the role for people like myself, to try and document these things for people who don’t have the opportunity to go and see them for themselves.

You have three kids about college age. Do you worry about the world they’re inheriting?

To be honest, it saddens me when I think about the things that I saw as a young man and if my kids went out, those things are no longer there. But the Earth keeps changing.

I do feel like my kids are inheriting a much more crowded and somewhat-diminished planet from the one that I found when I first started running around the world. It’s true. It’s sad, but that’s the honesty of it. I feel like part of what I can contribute is to try to make people aware of some of these changes so that hopefully we can move the needle in the right direction.

Get the Magazine

Become a member of The Nature Conservancy and you'll receive the quarterly print magazine

Subscribe now