The Burning Problem

TNC is helping farmers in India put out agricultural fires to reduce air pollution and improve soil health.

Winter 2022

In November 2018, a hospital in New Delhi installed a large set of artificial “lungs” in front of its property. Made of white HEPA filter material, the billboard-sized organs used fans to suck air through them. In a few days, they turned brown. Within a week, they turned black.

The headline-making stunt was meant to illustrate the severity of the city’s November air pollution. While more than 80% of Indian cities struggle with unhealthy air quality, the landlocked capital of New Delhi in the northern part of the country suffers the most toxic air—and it’s at its worst every year from October through December. During these months, a grayish-yellow haze hangs over the city, leading government agencies and the Environment Pollution Prevention and Control Authority to declare public health emergencies, shut down schools, halt construction work and ground flights due to poor visibility. Studies estimated that each year tens of thousands of citizens die from respiratory illnesses due to air pollution.

Sum of Many Fires

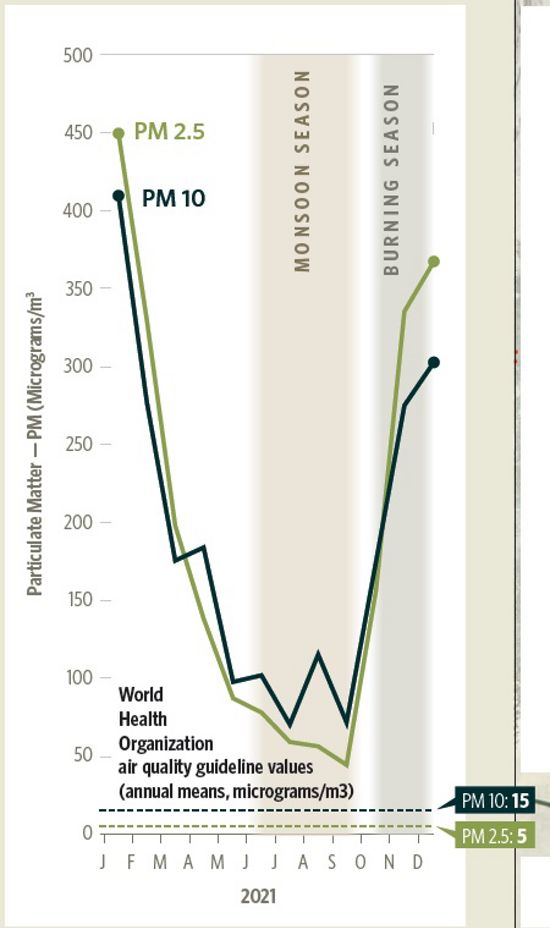

Though the capital region of Delhi suffers air-quality problems all year long, the levels of pollutants make a drastic spike from mid-October through mid-December. Part of the problem comes from thousands of upwind fields being set on fire. The chart to the left shows the levels of PM2.5 particles (sooty particles small enough to enter a person's bloodstream via the lungs) and PM10 particles (large enough to cause respiratory illness) that are recorded in Delhi. Pollution levels far exceed World Health Organization recommended limits.

This annual crisis is rooted in seasonally slower winds, mixed with smoke emitted from coal-fired power plants and exacerbated by thousands of fires in the agricultural fields of Punjab and Haryana, the two states northwest (upwind) of New Delhi. In this agricultural powerhouse region, farmers grow rice in the summer and wheat in the winter. But after harvesting the rice, they have very little time to prepare their lands for winter sowing, and the most cost-effective way to do this quickly is to set fire to the fields. The smoke from thousands of burning fields rides on prevailing winds, guided along the Himalayan Mountains, across northern India and directly into the capital of New Delhi and other nearby cities.

“It’s not like the farmers are too happy about setting fire to their fields, especially as they come under a lot of backlash over the pollution in New Delhi. The air here is also severely affected—it can lead to pileups on the roads owing to poor visibility during this time,” says Harminder Singh, a consultant field manager for The Nature Conservancy in India, who works closely with the farmers. “But this, unfortunately, is the most cost-effective solution available to them right now—especially the small and medium farmers.”

Since 2018, The Nature Conservancy has been working with local and regional partners to raise awareness among farmers about alternatives to crop burning. With the right technology and management practices, farmers won't need to set their fields on fire anymore, and they can improve their soil's health, reduce air pollution and even earn more money. But it will require millions of farmers to change the way they work.

Gurdeep Singh

Gurdeep Singh is a farmer from the Dhakraba village in the Patiala district of Punjab, where he lives with his wife, teenage daughter, mother and grandmother. He is a fourth-generation farmer and has been farming for 18 years and owns 18 acres of land.

Gurdeep, who has a bachelor’s degree, says he stopped burning his fields in 2017 when he first used a Happy Seeder. Today, he is constantly trying to persuade farmers to make the switch to new field management technologies. “I even tell them to try it out on my guarantee,” he says. “Nobody has been unhappy after trying these tools out, because they increase crop yield, and for a farmer there’s no better outcome than that.”

Gurdeep and his fellow farmers have taken to modifying the seeder that they share to improve its ability to cut rice straw. And he has been very engaged with TNC’s projects, learning new farming techniques and educating other farmers in his area. The best thing about the program, he says, is that they are working toward stopping environmental degradation. “It is something we all need to work toward—what use would a highly polluted, water-scarce world be to the future generations?”

The root of the problem dates back to the mid-1960s, when India needed to ensure food security for its growing population. More food could be produced each year if farmers grew rice in the summer and wheat in the winter. So the country incentivized farmers to adopt a rotation of high-yield rice and wheat crops. Encouraged by government subsidies, the primarily agrarian states of Punjab and Haryana largely shifted away from their traditional crops of corn, oilseeds, lentils, chickpeas and other legumes.

Today, the Government of India sets a minimum price for wheat and rice. If market prices dip, the government will buy from the farmers at the announced minimum price. That income security means Punjab and Haryana now produce much of the country’s grains. This agricultural force consists of thousands of family-owned-and-operated farms—most less than 10 acres. But some of the intensive farming practices devised more than 50 years ago are now proving harmful.

This decades-old decision has set into motion what has now turned into a catastrophic environmental problem. The climate in Punjab and Haryana is drier and not naturally suited for the cultivation of water-intensive crops like rice, so the dependence on irrigation has been high, contributing to alarming levels of groundwater depletion. To counter this, the Punjab government passed legislation in 2009 that farmers can sow rice paddies only during the monsoons—mid-June onward—to reduce dependence on irrigation. That delay often pushes the rice harvest into wheat’s growing season.

The wheat crop needs to be planted around mid-November, says Gurdeep Singh, a fourth-generation farmer who lives near the village of Dhakraba in Punjab. Any delay might affect the quality of the wheat harvest. This leaves farmers with only about eight to 15 days to clear the fields of the tough, stringy rice straw that is left behind by combine harvesters. Fire has offered the easiest solution to clearing the field in time. This means that all of the farmers have been forced to burn within a much shorter time frame than before, significantly adding to northern India's intense late-year air pollution problem.

Five years ago, Gurdeep used to burn crop residue on his 18-acre farm—but reluctantly. “There was no other way. Then, it was the most cost-effective option,” he says. Smoke during the burning period would make him sick, and visibility was so poor that it caused accidents on local roads.

Besides air pollution, crop-stubble fires harm the fields. The heat kills bacteria and fungi that lend soil its fertility, making crops more resistant to disease. Research published by the country’s National Policy for Management of Crop Residues found that burning one ton of crop stubble destroys 12 pounds of nitrogen, 5 pounds of phosphorous and 55 pounds of potassium—nutrients that would have otherwise returned to the soil but will need to be replaced via fertilizer.

Government and health experts agree that the burning needs to stop and farming practices must be reset. The National Policy for Management of Crop Residue advocates that stubble be incorporated back into the fields “not only to control crop residue burning but also to prevent environmental degradation in the croplands.”

That’s what TNC has been aiming to do with farmers since 2019, when it launched its HARIT project. This effort was aimed at encouraging farmers to start using a relatively new tool that would help them repurpose the crop stubble on their fields as a regenerative fertilizer. It allows farmers to improve the health of their soil, reduce the need for chemical fertilizers and retain moisture in the ground. And while farmers no longer emit carbon when burning crop stubble, the healthier soil in their fields can sequester more carbon than before.

Amandeep Kaur

Amandeep Kaur is not a typical Punjabi farmer. This is a male-dominated business, and she grew up helping her father work their family’s field. She also recently finished studying food processing at a college in Patiala.

In 2007, their family became the first farmers in their village, Kanoi, to use crop-residue management technology. "People would laugh at us and ridicule us for using the Happy Seeder,” Amandeep remembers. However, her family has always been against stubble burning because of its environmental damage—and also because they have suffered personal losses. “A portion of our field was burnt when a neighbor was burning the rice paddy straws in his field,” says Amandeep. This accidental burning of their field had cost them around $500 in losses (not a small amount for Indian farmers).

“We have always been against stubble burning,” she says.

During stubble-burning season “the weather gets oppressive. We don’t get to see the sun for days—a thick haze hangs over the village. We experience breathing difficulties, skin problems,” she says.

“And then we are also blamed for the pollution in Delhi—we feel bad.”

Amandeep has become a vocal advocate for adopting farming methods that don’t rely on field burning, and her family volunteers for trials of new field management tools that have been coming to the market. At present Amandeep is testing the Smart Seeder, which was designed by the Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, and given to some local farmers for trials.

She managed to persuade her maternal grandparents to stop burning their field, and they too adopted the new methods of farming. “In our village, around 70% of people are not burning their fields anymore.”

Now, Amandeep is considering how to form a group of young farmers to help spread the word. “The younger generation is more aware and against stubble burning. We are interested in new technologies and newer ways of making things work,” she says. “These projects are filling the gaps in information and action that existed before. I believe in a few years no one will burn their fields anymore. They won’t need to.”

This year, TNC launched a new project called Promoting Regenerative and No-burn Agriculture, or PRANA for short. It is funded by a grant from the Bezos Earth Fund. PRANA expands on HARIT by educating farmers on a multitude of new farming tools that can help regenerate soil health, and is also working to promote the diversification of crop production in an attempt to move away from intensive rice production that places strain on groundwater resources and affects soil health.

The first new technology to reach Punjab’s and Haryana’s fields bore the adorable name of Happy Seeder. It’s a machine that allows farmers to completely skip the step of burning old rice stubble. After the rice harvest is complete, the Happy Seeder—which is mounted on a tractor—cuts, collects and chops the leftover rice straw. The machine’s seed drill sows wheat into the soil, and then it deposits the straw over the sown area as mulch, which naturally traps moisture and improves soil fertility as it decomposes over time. It also suppresses weeds among the wheat crop.

“We have been working with the farmers, and there are 15 villages now where they practice no-burn agriculture,” says TNC’s Harminder Singh. Two years ago, he joined staff working on TNC's crop-residue management projects, teaching farmers in villages in the Patiala district about these new farming systems. Harminder explains to farmers how crop burning pollutes the air and damages the soil, forcing them to spend more money on fertilizer—reducing the profits of their harvest. Many farmers are skeptical about the upfront costs and abandoning long-held techniques, but Harminder says the possibility of improving their yields will usually get farmers interested.

“The quality of grain and the yield has improved significantly after using Happy Seeder,” says Gurdeep. He started using a Happy Seeder on his 18-acre farm in 2017, and he has become a local evangelist for the benefits of this new technology. “Crops are able to withstand strong winds and don’t fall off easily as compared to traditional farming methods.”

Since the Happy Seeder first came out, many similar-but-different implements have hit the market: Some, like the Super Seeder, churn stubble into the soil; others collect and bale it during the initial harvest; and so on. They all eliminate the farmers’ need to burn their fields, so the PRANA project is becoming technology-agnostic with plans to demonstrate and raise awareness of newer technologies to the farmers.

Sardar Amar Singh

Kularan, Punjab

One day in the 1980s, Sardar Amar Singh almost drowned in a well. The well was drying up, and the water was too far down for the owners to use their pulley-bucket system. Amar was hired to go down and install a pump. But they had miscalculated the depth, and Sardar found himself in trouble. It took him a few hours to be rescued.

“I have seen and experienced too much,” he says.

He started farming with a cattle-drawn plow, and now he sows with machinery. Sardar, 80 years old, owns 0.7 acres of farmland that give him a modest harvest. Even though his field is not large, he appreciates the importance of scientific farming methods and uses a Happy Seeder that he rents from another farmer. In fact, he has been one of the biggest proponents in his village of technologies that reduce field burning.

“People are interested in the new technologies that are now available in the market. There are so many options, and we learn about these options from [The Nature Conservancy’s PRANA] project,” he says. “They have made farming very easy—unlike when I was young and we had to do everything manually.”

Sardar is known to go around his village, trying to persuade farmers to switch to various new tools instead of burning their fields.

“Most people are willing to try these machines out. Punjab has always been mechanized—we are not afraid of trying out new machines,” he says. “But for small farmers these machines are expensive. More subsidies for small farmers will help in quicker adoption.”

The program aims to get hundreds of thousands of farmers to adopt a no-burn cropping system and eliminate the burning of crop residue on almost 2.5 million acres of cropland over the next years. If it can accomplish those goals, PRANA and its partners would prevent millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide from entering the atmosphere. Crop burning is outlawed in India and enforced with fines, but that has not been enough to dissuade farmers from practicing it.

To reach this large number of farmers, TNC has partnered with local agencies to increase outreach. They are also devising a pilot financial instrument to incentivize farmers to adopt no-burn practices to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The cost of these new farming tools presents a hurdle to achieving widespread adoption. Gurdeep’s farm is not big enough to justify buying a seeder that will be used only a few days per year. So he partnered with a group of nine farmers to buy a Super Seeder and a reversible plough. “We also rent them out to other farmers,” he says.

The Government of India's Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare launched a program in 2018 to help farmers in the states of Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh (plus some areas around New Delhi) buy the new equipment. The subsidies include 50% of the machines’ price for individual farmers, while the government covered 80% on machines bought by farmers groups and cooperatives.

“If [farmers] are convinced that using the crop-residue management technologies might involve initial expenses but that in the long run it will increase their income as well as take care of the environment, they will be more interested,” says Guru Koppa, PRANA’s project director.

A study published in the journal Science, co-authored by TNC staff members and various other academic, research and agricultural entities, demonstrated that farmers using the Happy Seeder experienced cost savings and improved productivity. On average, integration of the Happy Seeder increased net profits by between 10% and 20%.

“At least 75% of farmers in the villages under me have started using the Super Seeder,” says Raghuveer Singh, the headman (a title for local government representative) of Kansuha and 25 other villages, where TNC has been active. “We have all experienced improved yield and soil quality.”

In summer, the Punjab village of Sauja is surrounded by rows of bright green, swirly rice crops sitting in wet paddies. While thousands of fields across Punjab are burned each November, last year in Sauja was very different. More than 80% of the village’s farmers have stopped burning their fields.

“Villagers who are educated and aware understand the negative impact on the environment," says headman Bahadur Singh. "They openly speak about its impact in their village and cities adjoining Punjab. They know that the only way to deal with this is to use the crop-residue management machines.”

In Kansuha, too, stubble burning has been dramatically reduced. “Over the last two to three years, the use of Happy Seeders and Super Seeders has been rising,” says Bahadur. Apart from improved crop yields, the weather is better in October and November. “We can actually see the sun now,” he says with a laugh.

If this progress continues, northern India and New Delhi might be able to see the November sun, too.

Magazine Stories in Your Inbox

Sign up for the Nature News email and receive conservation stories each month