From the Mountains to the Sea

Hawaiians are reviving traditional land management practices to restore a watershed on the island of O‘ahu.

Summer 2022

On O‘ahu, just 14 miles from downtown Honolulu, Kāne‘ohe Bay has long seemed a world apart—a serene idyll framed by the lush Ko‘olau mountain range. In the early 2000s, the turquoise lagoon—the largest sheltered body of water in the Hawaiian Islands—was as picturesque as ever. But beneath the surface, the bay was in trouble.

Invasive algae smothered the coral reef. The mountain streams that fed the bay carried pollutants—suburban runoff, sediment and debris—if they flowed at all. Invasive mangroves choked the shoreline, turning the tidal flats into a weedy mess.

The Nature Conservancy teamed up with the University of Hawai‘i and the state’s Division of Aquatic Resources to clean up the bay. In 2005, they deployed a device nicknamed the “Super Sucker” to vacuum suffocating algae off the reef. Then they brought in hundreds of thousands of native sea urchins to prevent the algae from growing back on the reefs or spreading to other parts of the island. The results were dramatic: Corals freed from algae immediately began to recover.

But bigger questions hung over the bay: What had caused this imbalance on the reef? And what could be done to make the bay’s ecosystem more resilient?

A Native Hawaiian scientist and seaweed expert on the TNC team, Koa Shultz, turned his focus inland. He began meeting with local elders to discuss the possibility of reviving a traditional Hawaiian land-management concept that views upland and coastal waters as intricately connected.

Long before ecologists coined the word watershed, Hawaiians divided their islands into numerous “ahupua‘a,” districts that usually ran from the mountain ridgelines down to the reefs. Each district was ecologically and culturally self-sustaining. Its inhabitants cared for and harvested its natural resources—timber and medicinal plants in the upland forests, taro patches in the valleys and fish in the nearshore waters.

“Whatever a person needed could be found within their ahupua‘a,” says Shultz. “Some were big, some were small; it depended on how rich each was in production.”

The system not only helped feed people but supported a wide array of wildlife as well. Farmers diverted water from mountain streams into paddies to grow the root vegetable taro. And those farms offered prime habitat for native waterbirds, freshwater fish and invertebrates. The water would drain back into the stream and continue to the sea, delivering nutrients to the estuaries. Hawaiians built large, rock-walled fishponds at the mouths of streams where juvenile marine species flourished. Besides providing the nutrient-rich staples of the Hawaiian diet, taro patches and fishponds also functioned as filtration systems, absorbing floodwater during storms and mitigating the impact of runoff into the bay.

Although the ahupua‘a system sustained the Hawaiian people for generations, it has been long gone from the landscape. In the 1800s, foreign colonization and the imposition of private land ownership systems drove Hawaiians out of their ancestral spaces.

Today, however, a quiet renaissance is unfolding here. Native Hawaiian-led community groups have united with TNC and several public agencies to restore the He‘eia ahupua‘a, a fertile 7,691-acre region that reaches from the ridgetops down to Kāne‘ohe Bay. The restoration at He‘eia provides a new model for large-scale restoration of Hawaiian culture and the environment.

Just past what locals call “the long bridge” on the Kamehameha Highway, Shultz rolls his truck to a stop. The spot offers a vantage of nearly the entire He‘eia ahupua‘a. The rain-carved, velvet green Ko‘olau mountains hang like theater curtains behind a broad meadow. During big rains, waterfalls cascade down the steep ridges to flow across the plateau and merge with the sea here, beneath this bridge. Across the highway lies sparkling Kāne‘ohe Bay and one of the few surviving fishponds on O‘ahu.

Until a few years ago, a thicket of mangroves obscured this view—and impeded the flow of water. Shultz waves hello to a crew felling trees with chainsaws alongside the road. The person in charge is his friend Hi‘ilei Kawelo, one of the fishpond’s current caretakers.

In 2001, Shultz, Kawelo and six other young Native Hawaiians founded Paepae o He‘eia, which translates to “Supporting He‘eia,” a nonprofit devoted to breathing life back into the He‘eia fishpond. Two decades later, Kawelo—as muscular and enthusiastic as the college students she now supervises—is the executive director of Paepae. “Fishpond work is hard,” Kawelo says over the roar of saws. “But when you get out onto the wall and see the ‘ama‘ama [striped mullet] jumping and frolicking, it’s the most beautiful thing in the world.”

From the highway, the He‘eia fishpond looks like a mere ring of rocks. In fact, it’s a living artifact constructed between 600 and 800 years ago. Thousands of Hawaiians passed rocks hand to hand to build a wall 15 feet wide and more than a mile long, enclosing 88 acres of the lagoon.

In centuries past, communities constructed massive coastal ponds like this throughout the Hawaiian Islands. Rugged, dry-stacked rock walls withstood pounding surf and featured an ingenious innovation: the sluice gate. The gate’s narrow slats allowed juvenile reef fish to enter the pond, where they would grow fat—too fat to swim back out. During tidal shifts, mature fish gathered at the gate, where the fishpond’s caretaker would scoop them up or release them to spawn and repopulate the coastal waters. The trees that Kawelo and her crew are cutting today will be used to make a new sluice gate, one small part in bringing the He‘eia ahupua‘a back to life.

Kāne‘ohe Bay once boasted more than 30 fishponds, but most of those disappeared in the 20th century. In 1965, a flood blew out a huge section of the He‘eia fishpond’s wall, and it too began to fade into the sea.

The Paepae o He‘eia crew took on the painstaking work of rebuilding the wall. A massive Pani ka Puka, or “Close the Hole,” campaign drew thousands of helping hands, echoing the construction effort of days past. Volunteers also attacked the mangroves that had wrenched apart the fishpond’s walls, pulling up saplings by hand and felling larger trees with chainsaws.

Today, the fishpond’s wall is whole again and mostly mangrove-free. Small schools of milkfish and mullet gather at the sluice gate, where visiting seventh-graders flash euphoric smiles as they’re mesmerized by the darting fish.

“When you talk about restoration of the ahupua‘a, it’s easy to focus on taro, fish and walls,” says Kawelo. “Really it’s about water and relationships. That’s the blood that flows through our veins.”

Fresh water is the silver thread that runs through the ahupua‘a, connecting each ecosystem to the next. While Paepae o He‘eia rehabilitated the pond, another group tackled the problems upstream. In 2006, Richard Barboza and Matthew Schirman established Papahana Kuaola, which roughly translates to “Mountain Project,” on 63 acres straddling Ha‘ikū Stream at the base of the Ko‘olau mountains. When they first moved in, the site was an illegal dump. Volunteers hauled out trash, fortified the stream banks and replaced erosion-causing weeds with native shrubs and trees.

Today, Papahana Kuaola, with six full-time employees, is part farm, part educational center—a vibrant place that offers local students and community members hands-on lessons in traditional agriculture and native stream ecology. A freshwater spring feeds a series of taro patches. Breadfruit and banana trees shade the path to the stream, which now runs clean.

With restoration underway in the mountain stream and marine ecosystems of He‘eia, all that was missing was the middle. The enormous meadow between the mountains and the bay once supported one of Hawai‘i’s most extensive wetland farming complexes. Hundreds of taro patches nourished the community and acted as a buffer for the bay, but they had lain fallow since the 1940s.

When Shultz started working in Kāne‘ohe Bay, he met with members of the Ko‘olaupoko Hawaiian Civic Club who remembered ahupua‘a in the He‘eia taro patches. Ninety-three-year-old Alice Hewett owned the last poi mill in He‘eia, and Leialoha Kaluhiwa’s grandfather was the last traditional caretaker of the valley. With their guidance, Shultz took on the added role of executive director of Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi, which roughly translates to “Helping Native Hawaiians,” a nonprofit dedicated to reviving the historic farmland.

“Koa kept telling us the importance of working here,” says Eric Conklin, TNC’s marine science director for Hawai‘i. “At the time we were focused on coral reef protection, not food security and lowland restoration. But Koa showed us how a taro farm could act as a giant water filter, keeping sediment off the reefs and out of the bay. Ultimately, the project was a great opportunity to address mauka [mountain] pressures on makai [ocean] ecosystems—and a critical step in our program’s evolution of incorporating traditional knowledge into our work.”

The Conservancy gave Shultz the green light to work at Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi full-time, paying his salary and providing the science needed to back the nonprofit’s ambitious initiatives. Then, in 2009, the state granted Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi a 38-year lease to roughly 400 acres of land—and the last, largest piece of the ahupua‘a snapped into place.

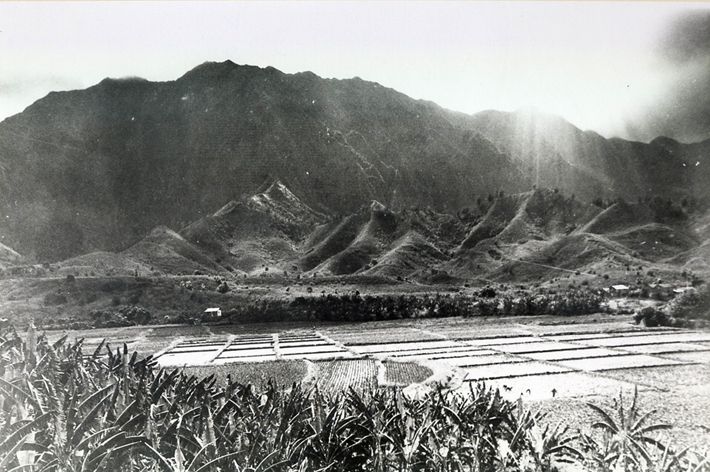

Shultz carries a laminated black-and-white photo with him like a talisman: an aerial image of He‘eia in 1928. Wisps of clouds frame a patchwork quilt of taro patches. The tidy fishpond looks like a stone and coral lei draped across a corner of Kāne‘ohe Bay. Beyond the pond, fringing coral reef reaches into the deep Pacific. The image captures more than mere geography; it reveals how Hawaiians once thrived within an intact watershed. And in Shultz’s hands, this snapshot of the past has become a blueprint for the future.

For years, volunteers had battled the mangroves with hand tools. But once the community had a lease for the 400 acres of meadow and more funding, they brought in heavy equipment. As excavators knocked down 80-foot-tall mangroves and the native wetlands were reestablished, the view opened up—and so did people’s imaginations.

The intensified restoration effort was not without risk. “The real fear was that taking down the trees would release sediment,” says Kim Falinski, TNC’s marine science advisor for Hawai‘i. “One big storm and you could have a meter of [mud and] leaf litter from 12 acres smothering the reef.” She worked with Shultz to model how the mangroves could be removed with minimal effects on the marine ecosystem.

Careful monitoring showed that the sediment stayed put. And, in the wake of the tractors, Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi brought in sheep. Today, a flock of 45 of the animals helps mow down invasive grass.

Shultz looks out over a newly planted taro patch. Row after row of heart-shaped taro leaves wave on slender stems. An endangered Hawaiian black-necked stilt dips its beak into the mud, foraging for a snack. “The taro patch is an education in how to bring back life,” says Shultz. “Taro is king. It benefits our people, it benefits our land.”

Taro once covered tens of thousands of acres throughout the Hawaiian Islands. According to the most recent estimates, only some 700-800 acres are planted statewide. Resurrecting historic patches in He‘eia could, Shultz says, increase commercial taro production on O‘ahu by at least 400%.

The Heart of Hawai'i: Taro farming restores a food staple at the center of local tradition

When Polynesian voyagers first reached Hawai‘i, they carried a survival kit of food crops from the more westerly islands of the Pacific. That assemblage of species, known as “canoe plants,” included taro, bananas, coconut and breadfruit, and proved key to gaining a foothold on the remote and often-inhospitable islands and atolls of Polynesia.

Taro played a particularly important role in Hawai’i, where it became a staple of the Hawaiian diet and a foundation of the culture. Today, far fewer taro farms exist than in days past, but people in Hawai‘i still cherish taro and treat it with reverence.

Traditionally, Hawaiians cook taro in an underground oven. They mash the steamed roots with stone pestles into a smooth sticky paste called “pa’i ‘ai.” When water is added, this paste becomes poi—an earthy delicacy unique to Hawai‘i. Warriors eat the nutrient-dense starch for strength, mothers feed it to their babies, and healers use it to nurse patients back to health.

Poi remains essential at any island celebration, or “lū’au.” But taro is also enjoying a kind of fusion revival: You can order taro burgers, waffles and croquettes at restaurants and find taro-based baby food in grocery stores.

In just over a decade, Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi has grown to 16 staff and an anticipated annual revenue of $1 million. The farm sells poi made from taro statewide, as well as banana, breadfruit, fern and sweet potato, and all the profits go back into watershed restoration, education and management of the ahupua‘a. Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi hosts island school groups and farm apprentices, and 30 small taro patches are reserved for local families to feed themselves; a traditional Hawaiian healer has planted a medicinal garden as well.

Every day, He‘eia begins to resemble the vintage photo a little bit more. A close look at the black-and-white image reveals three small buildings. They are poi mills—simple field kitchens where taro was steamed, peeled and pounded into poi. In 2021, the Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi team built a new mill: a beautiful kitchen with multiple sinks for washing muddy taro corms, huge walk-in freezers and large windows facing the mountains. Shultz is eager to launch the farm’s new lines of produce and poi.

“Koa has made things happen here that I would have sworn were impossible,” says Conklin. “This went from a beautiful vision to a fundamentally transformed landscape.

The effort to restore the He‘eia ahupua‘a got a significant boost in 2017, when the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration designated the area a National Estuarine Research Reserve. It’s one of 30 sites nationwide created to protect and study estuarine systems—and among the first to incorporate Indigenous knowledge.

Kawika Winter, the reserve’s director, is especially excited to integrate Indigenous science with conventional science. “He‘eia is one of the best places to bring together the best of both worlds,” he says. “The ahupua‘a is a viable model for the 21st century. But all these organizations working on their own areas don’t have the capacity or time to think about how to connect all the dots.”

The reserve and TNC have helped connect the various groups, facilitating collaboration and securing funding.

“What’s so exciting is that He‘eia brings together all of these different partners and goals—for biological conservation, revitalization of cultural practices and economic advancement,” says Conklin. “We’re able to work at a scale together that none of us could achieve alone.”

Ryan Okano manages the Hawai‘i Division of Aquatic Resources’ ecosystem protection program. “We see He‘eia as a laboratory,” he says, noting that his agency plans to apply the restoration lessons from He‘eia to other places in the state. “This stuff is cutting-edge: Nobody knows what will happen in 20 years after you cut down the mangroves.”

So far, the evidence is encouraging. Okano has received eyewitness accounts that during the latest flood, “less sediment pushed into the stream and onto the reefs than in prior events.” And now that most of the mangroves are gone, the estuarine waters are starting to take back the wetland.

“That tidal mixing might be able to come back just a little,” says Falinski. “That means that [flagtail] fish and all these creatures that like brackish water are able to come back.”

Native bird species are thriving, too. Not only have Hawaiian stilts returned, but an even rarer species has started nesting in the marsh where the mangroves were removed. Only a few hundred ‘alae ‘ula, or Hawaiian common gallinules, exist on Earth. Remarkably, 20 of them now live here.

After a long day, Shultz turns his truck toward home. On the way out, he spots an ‘auku‘u (black-crowned night heron) stalking something in the marsh between two native sedges—it’s a juvenile ‘alae ‘ula. He slams on the brakes, jumps from the truck and shoos the heron away from the gangly chick.

“They need all the help they can get,” Shultz says. He’s as thrilled as a new father at the sight of the youngster—evidence of a new nest and a hopeful future.