African Oasis: The Okavango Delta

To safeguard the Okavango Delta, one of the largest wetlands in the world, TNC is starting at the source.

Spring 2021

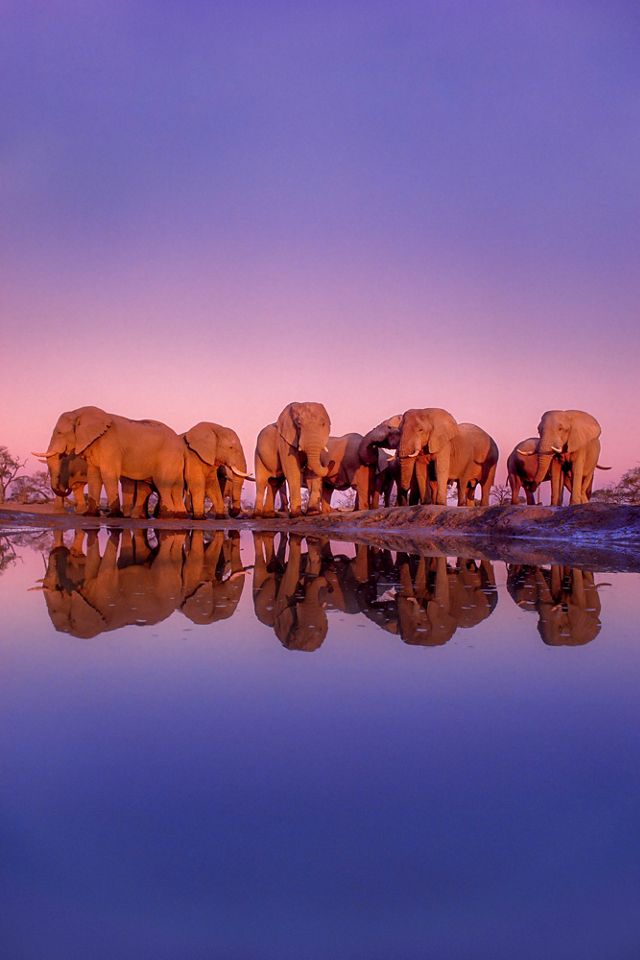

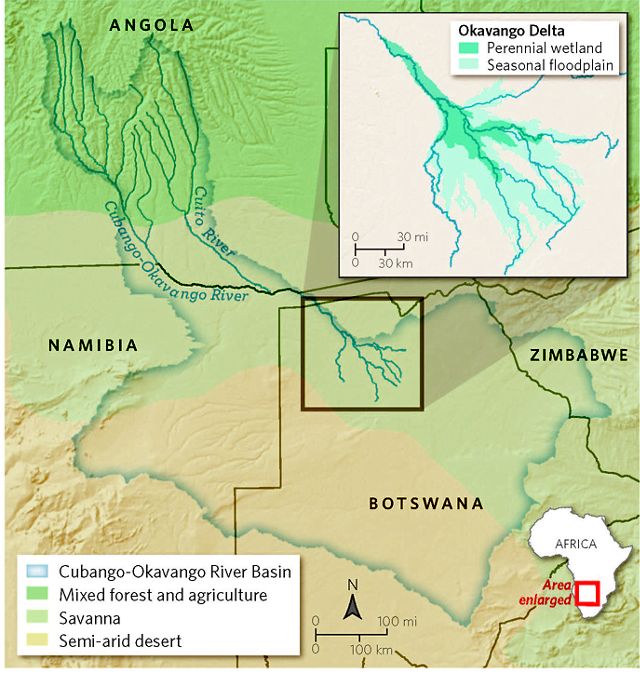

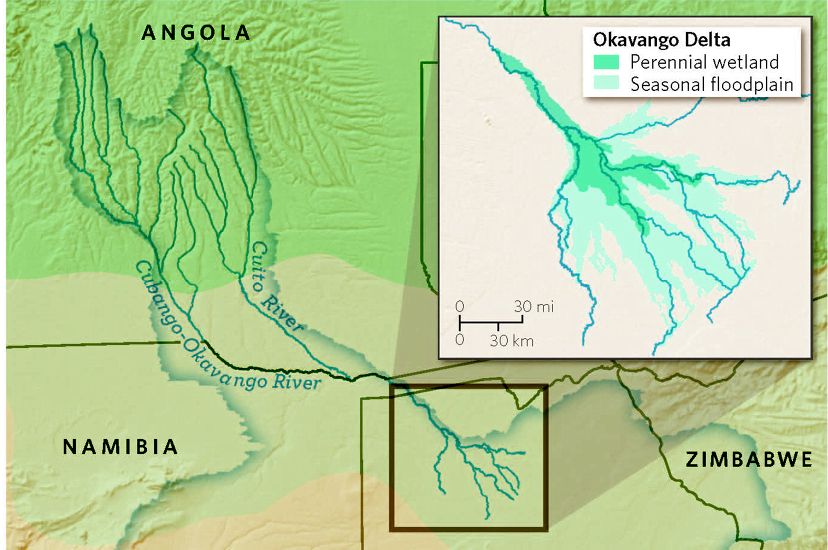

At the height of Botswana’s six-month dry season, rainwater from Angola’s lush highlands spills into the heart of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa, setting in motion an ecological spectacle unlike anywhere else on Earth. With the influx of 2.5 trillion gallons of water, the Okavango Delta—a permanent swamp surrounded by one of the continent’s driest expanses—doubles in size. Fueled by the promise of a fertile floodplain, some 200,000 large mammals return to the delta, now an oasis roughly half the size of Massachusetts.

The floodwaters usher in more than 700 species of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and reptiles. African fish eagles soar above prides of lions and the continent’s largest population of savanna elephants. Wild dogs prowl through thorn scrub as cheetahs stalk warthogs and wetland antelopes. Hippos and Nile crocodiles lurk among reeds and papyrus. The delta hums with life for several months until the floodwaters evaporate or recede into the red desert sands.

The Cubango-Okavango River Basin covers 125,000 square miles in Angola, Namibia and Botswana and provides water for 1 million people. Widespread poverty plagues the upper basin, and the majority of people rely on livelihoods like agriculture, fishing, forestry and tourism that draw on the region’s natural resources. The delta itself is largely protected by a mosaic of game reserves, wildlife management areas and community trusts, but most of the biodiversity-rich lands, rivers and lakes in Angola that feed it are not. And as the country emerges from decades of civil war, more than 50 large-scale water infrastructure projects are under consideration, including dams for hydropower, commercial irrigation works and municipal water storage. These projects could divert floodwaters away from the delta, disrupting one of the most magnificent large-animal migrations in the world and crippling the livelihoods of the people who depend on it.

Now is the time to act to protect the Okavango by creating viable alternatives for Angola to grow and develop, says Matt Brown, regional managing director for The Nature Conservancy in Africa. “If we can get it right now, we can save one of the most amazing natural places in the world, before the threats become a reality.”

Protect the Okavango

Your support will help keep this wonder of the natural world intact.

Donate nowSince 2018, TNC has been partnering with the government of Angola and the Permanent Okavango River Basin Water Commission (OKACOM)—as well as organizations including the World Wildlife Fund, Peace Parks Foundation, Conservation International, Namibia Nature Foundation and National Geographic’s Okavango Wilderness Project—on a three-pronged approach that balances the needs of people and nature across the basin. The first goal is to plan smart development in the headwaters region of Angola. To that end, TNC is working with the Angolan government and international energy company Gesto to create a master plan that prioritizes low-impact renewable energy sources, like solar power, over traditional large-scale hydropower. The effort could help protect nearly 33,000 acres of critical floodplain habitat by carefully siting low-carbon energy projects away from wildlife corridors and intact natural landscapes.

Community-based conservation also is critical, says TNC’s Okavango Basin Program Director Sekgowa Motsumi. “People are dependent on natural resources. We want to help them take full ownership of these resources, manage them and also derive a livelihood.” Workshops with communities and local partners such as the Association for Environment Conservation and Integrated Rural Development are a key part of pilot projects in forestry and fisheries. The work capitalizes on TNC’s track record of creating natural resource management plans in Kenya and Tanzania, and includes the first-ever nationwide meeting of community-based conservation organizations in Angola.

Quote

More than 50 water infrastructure projects could divert floodwaters away from the delta, disrupting one of the most magnificent large-animal migrations in the world.

To support these efforts into the future, TNC, along with its partners, codeveloped a long-term financing plan designed to fit the complex politics and geography of the basin. While Angola provides 95% of the delta’s water, it is Botswana that largely reaps the benefits of ecotourism centered on the region’s annual wildlife spectacle. In short, development decisions made upstream have a significant effect on the people and animals who live downstream. The Cubango-Okavango River Basin Fund will aim to balance the economic disparity on both sides of the basin by supporting community development efforts while also promoting the sustainable use of natural resources. The Conservancy has created similar water-protection funds in Ecuador, Kenya and South Africa.

Making an impact at the scale of a river basin requires an extensive coalition of partners, donors and governments, and two years in, TNC’s efforts are showing great promise, Motsumi says. In addition to bringing together multiple organizations, TNC is working closely with the governments of Angola, Botswana and Namibia through OKACOM, a planning group, to jointly manage water resources and encourage sustainable development in the region.

This is the first step of a decades-long project to ensure the Okavango endures, Brown says. “We have to protect this place. We can’t let it disappear on our watch. We have the tools to do it.”

Get the Magazine

Sign up to become a member of The Nature Conservancy and you'll receive the quarterly print edition of the magazine as part of your membership.