Letting the River Run

As floods throughout the Mississippi River Basin become more destructive, communities are changing tactics to give the water a place to go.

Spring 2021

Most years, the option on the table would be unthinkable: Some farmers would permanently stop working their lands, ceding them to a nearby river. But in November 2019, at a meeting of Missouri state officials, farmers groups, local officials and residents of a badly flooded community, the farmers themselves advocated for the idea. Riverside farming had become risky business on their low-lying properties. If they couldn’t control the river that kept inundating their community, maybe they could give the river more room to spread out and slow down during future floods.

“We need something so we aren’t doing this every year,” Ryan Ottmann, a farmer and the president of the Atchison County Levee District, told the group.

Located in the northwestern corner of Missouri, Atchison County is home to 5,100 people. Its county seat, Rock Port, claims to be the first U.S. town to rely entirely on wind power. About 400 farms—most family-run—grow soybeans, corn and hay on lands near the Missouri River, which snakes along Atchison on its way to join the Mississippi just north of St. Louis. Much of the river is lined with levees that keep the water out of the fields and communities alongside it.

But on March 14, 2019, a dam on an upstream river collapsed. Three days later, the Missouri River started breaching two major levee systems in Atchison County. More floods and breaches followed, and the river surpassed its banks for months: A county emergency manager called the floods “never-ending.” In Atchison alone, 166 homes flooded, and 278 residents were forced to evacuate. All told, 56,000 acres of land were submerged—some until December. The area lost an estimated $25 million in agricultural revenue, as water and debris destroyed crops, damaged lands and washed soil downriver.

How the Water Shapes Us

A photoessay celebrates the environment and culture along the Mississippi River

Mississippi River Photoessay2019: A Historic flood year in the Mississippi River basin

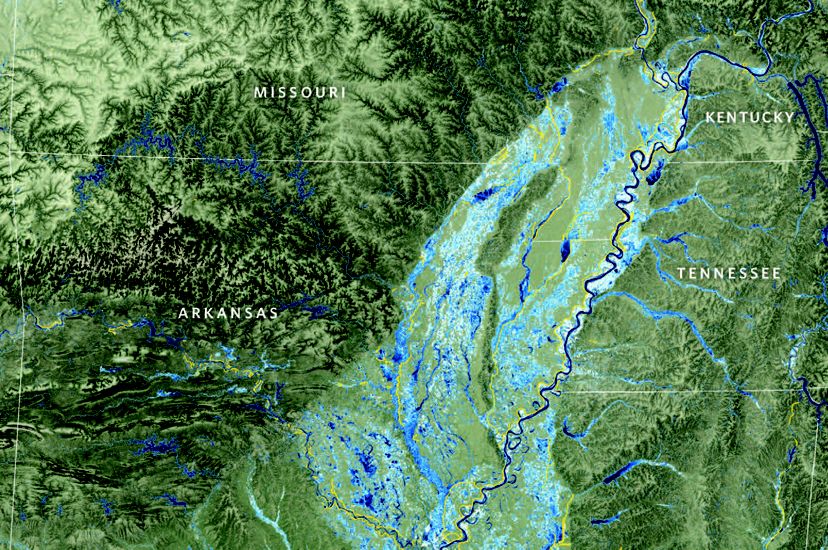

What happened in Atchison County was just a microcosm of what happened across the Midwest and parts of the South that year. The 2019 spring floods broke records in many parts of the Mississippi River basin—a vast swath of land stretching across 31 states and into Canada. River levels peaked at record highs in 75 locations in the Missouri River basin alone, and constant high water weakened levees until they collapsed. And in one Louisiana town, water seeped under a levee and wiped out a water-treatment facility. In Nebraska, an Air Force base flooded. The federal government later estimated the floods along the Mississippi caused $20 billion in damages. At least 14 people died.

Historically, the Mississippi and the major rivers that flow into it—the Missouri, the Ohio, the Arkansas and others—would have flooded seasonally into the lands that abut the rivers. Known as floodplains, these low-lying areas would have absorbed some of those floodwaters and spared those living downstream. But for more than 300 years, towns, farms, military bases and homes have been built on these lands. Communities have constructed levees along the riverbanks to protect themselves from floodwaters. Those levees constrict the river and push more water downstream, creating higher and higher water levels. As rains have become more extreme because of climate change, many communities are stuck in a pattern of flooding and rebuilding.

Numerous agencies, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, along with environmental groups like The Nature Conservancy, Ducks Unlimited and others, are working with communities to find ways to reduce extreme flooding and restore some of the floodplains the rivers once relied on. And the communities themselves are increasingly advocating for living with the river rather than fighting it.

At the November 2019 meeting in Atchison County, an Army Corps representative named Dave Crane presented two options to the group for repairing or replacing the pair of federal levees that had collapsed. The Corps could plug the holes in both of them. Or it could rebuild them farther back from the main navigation channel of the river, on what was mostly private land. That would let the river spread out during floods, keeping the water levels lower.

Ottmann, from the levee district, spoke in favor of a setback. “You have a 67-year-old levee that is damaged,” he told the group. “We have a broken system—not just in the breaches.” Maybe, instead of the status quo, they, like many other communities in the Mississippi River basin, needed a change.

The Mississippi: Engineered to be more a highway than a river

The main stem of the Mississippi River has connected humans for millennia. People of the Mississippian Culture grew food and traded along the river. Since the 1800s, barges have carried goods up and down the river for shipping out of New Orleans to the rest of the world. And from New Orleans to Memphis to St. Louis and onward to Minneapolis, the river has been a common thread across culturally diverse regions.

Rain that falls from Ohio to Montana to Louisiana eventually meets in the Mississippi River; it is the product of more than 300,000 miles of smaller rivers, creeks and streams poured into one. Without human intervention, the Mississippi would, like all rivers, change paths over time, altering its meandering curves as it eroded away land. Spring rains would drive pulses of water downriver, flooding nutrients over its banks to create fertile plains or forests. More nutrients and sediment would travel south to wetlands at the mouth of the river on the Gulf of America.

But in 1928, after a historic flood, the federal government authorized the Army Corps to begin a massive program to build levees and dams on the river. Today, 80% to 85% of the Mississippi River from Davenport, Iowa, to the Gulf of America is leveed, disconnected from its floodplain, according to Gretchen Benjamin, TNC’s large-river specialist. That infrastructure did its main job of keeping water inside the river for decades. But increasingly frequent floods, like those in 1993, 2008, 2011 and 2019, have made life on the river more dangerous.

In many ways, the modern Mississippi is more a highway than a river. It is continually managed to maintain a navigation channel for the barges that carry more than 500 million tons of cargo annually. “We really don’t let it function like a natural river,” says Benjamin. “It’s highly manipulated for people.”

Benjamin grew up five blocks from the Mississippi in a Minnesota town that didn’t have a levee at the time. Now, like many living in the northern reaches of the river, she kayaks on it and visits it with her family. The river is part of a wildlife refuge there—a different beast than the leveed stretches to the south.

For the past decade, Benjamin has been part of a team at TNC working to restore and—where possible—reconnect 750,000 acres of the basin’s floodplains to the river. She and TNC are not alone in the effort to restore Mississippi floodplains. States and other conservation groups throughout the basin are trying to mitigate the damage that comes with every wet season. And the U.S. Department of Agriculture manages the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program and Wetland Reserve Easements, a program that buys easements on vulnerable farmlands that are converted back into wetlands and other wildlife habitat.

More extreme weather is putting more people at risk

Meanwhile, the risks are rising. Throughout the Midwest, climate change is causing more extreme weather patterns. Heavier rains are dumping more water into the watershed in shorter periods of time, creating more frequent extreme floods.

“Our new normal is high water,” Benjamin says. “And the infrastructure that was built on the river for humans isn’t set up to deal with these high water levels.”

A study published in Environmental Research Letters in 2018 found that nearly 41 million Americans are at risk from flooding rivers. And that number likely will increase in the coming decades.

A new levee plan emerges in a Missouri county

It was April 2020 in Missouri. Barbara Charry, the floodplains strategy manager for TNC in Missouri, presented to the state’s Flood Recovery Advisory Working Group about an online mapping tool TNC was using to help state and federal agencies plan for flooding near St. Louis along the Meramec River. Recommendations for the Meramec plan included wetland restoration, a flood warning system, flood insurance and buyouts of particularly vulnerable land.

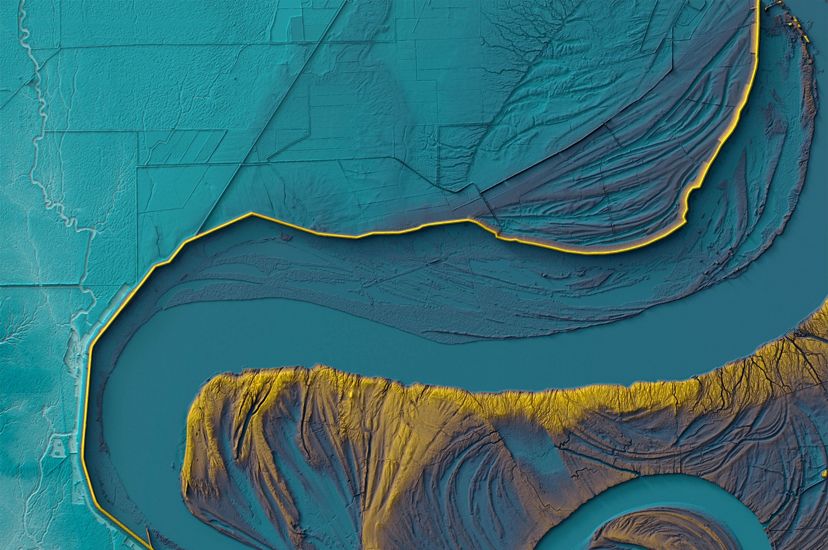

Developed by TNC, the Floodplain Prioritization Tool, she told the group, was designed to help communities identify the places where restoring floodplains could be particularly effective. With the map-based tool, they could see where conservation or restoration of floodplains could provide the most benefits for habitat, water quality, and future damages to property. Models have shown that where a river is allowed to expand, flood levels and water velocity can be reduced, preventing greater damage locally and downstream.

In Support of Freshwater

In 2017, the Enterprise Rent-A-Car Foundation—the philanthropic arm of the international rental car company—donated $30 million to enable TNC’s global conservation work for rivers. “Enterprise has deep roots in St. Louis, and one of the world’s greatest rivers, the Mississippi, runs right through our hometown,” says Carolyn Kindle Betz, president of the foundation. The gift is advancing TNC’s work with the Mississippi and Colorado Rivers, the waterways of Canada’s vast boreal forest and the remaining free-flowing rivers of Europe. Today, TNC is sharing new strategies to help farmers and ranchers reduce field runoff into rivers, work with Indigenous communities in the stewardship of their forests and lakes, help governments explore ways to meet energy demands without putting large hydropower dams in harmful locations, and much more. “It was important that this gift benefit communities and their surrounding environment worldwide,” says Betz. “We hope it will help more people understand and support the critical role rivers play in our lives.” —Eric Seeger

Charry had become involved in the Atchison County levee discussion after an Army Corps employee reached out to her, asking if TNC would be interested in buying floodplain property. Local support had coalesced around the idea of rebuilding one of the two damaged levees farther back from the river, adding about 1,100 acres back to the floodplain. But there was a catch: The relocated levee would run through private property and turn former cropland back into unfarmable wetlands.

Charry began convening meetings among a wide spectrum of organizations and groups of people to find a solution. Ultimately a commitment from TNC to purchase the land in the floodplain, together with payments for emergency floodplain wetland easements from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, ensured that the landowners would be compensated. The Army Corps and Natural Resources Conservation Service would replant the fields with native plants and restore wetland habitat, with the intention of eventually turning it over to a state agency.

What happens upstream affects those downstream

Throughout the basin, decisions made upriver affect those downriver, for better or worse. But that doesn’t make giving up family land or altering a way of life any easier.

One rural community on the Illinois-Missouri border in an area known as Dogtooth Bend is grappling with that change. After multiple breaches and floods, the Army Corps determined that rebuilding the area’s levee wasn’t financially feasible. In 2019, landowners willing to allow their farmland to be converted back to functioning floodplains began applying for wetland easements through the federal Natural Resources Conservation Service, which compensates them, but there is currently more interest from landowners than there is money to pay them.

Meanwhile, Memphis, about 180 miles down the Mississippi from Dogtooth, is in the process of revamping a 30-acre park on its riverfront—the latest in an ongoing effort to reclaim the city’s historic and cultural connection to the river. That process includes constructing wetlands to absorb floodwater when the river rises.

Cities throughout the basin are exploring similar projects, says Colin Wellenkamp, the executive director of the Mississippi River Cities and Towns Initiative and a St. Louis resident. Many are slowly moving infrastructure away from the river. But downriver, cities can only do so much to protect themselves. Some have begun to reconnect to the river backwater areas in their jurisdiction, but by and large they’re relying on vast agricultural land upstream to absorb more floodwater.

Near the end of the Mississippi River, New Orleans is about to become part of what could be the most ambitious project on the river. For millennia, the Mississippi carried sediment downstream and deposited it at the mouth of the river, constantly building wetlands and barrier islands that helped protect the coastline from storms and erosion. But since the river was leveed, this process has all but stopped, and the delta has lost more than 440,000 acres of land, endangering the coastline and the city of New Orleans. Now, however, the state of Louisiana has begun planning for two “diversion” projects that aim to allow sediment into the delta again. One of them will send more water and sediment away from the city and back into the Atchafalaya River, a 1-million-acre bayou ecosystem of slow-flowing rivers and lakes that has historically carried Mississippi River water to the Gulf of America. The swamp supports more than 400 wildlife and aquatic species. The Conservancy has spent the last 10 years working with the state and landowners to protect the Atchafalaya.

When all of these projects work, they have the potential to reduce flooding downstream and improve water quality, advocates say. But because each area relies on communities upstream, it takes good neighbors to keep the floods at bay.

That’s one thing Chris Rice, a Louisiana biologist, points to in his county. He was hired by TNC in 2009 to work on what would become the largest floodplain restoration project in the Mississippi River Valley. Formerly known as Mollicy Farms—the site of a failed soybean farm—the restoration project began, like so many others, with a levee breach.

In 2009, TNC and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had planned to breach a levee separating the Ouachita River from the 16,000-acre property, which TNC had bought from its former owner. But then the river took matters into its own hands and blew out the levee for them.

“When the breach happened, the water levels downstream in Monroe, Louisiana, dropped about a foot,” says Rice.

The land, since replanted with bald cypress, oak, cottonwood, ash and other trees and reconnected to the river in multiple locations, is now part of the Upper Ouachita National Wildlife Refuge. Fish are able to venture from the river into the restored wetlands to forage for food. And the former farm is once again a stopover for migratory birds.

In 2020, the waters stayed mercifully low in much of the Upper Mississippi River basin. In Atchison County, Missouri, the Army Corps patched and repaired one of the two damaged levees as it stood. The setback of the other levee began in August and is scheduled to be finished by April 2021.

Next, restoration will begin on the 1,100 acres of land reconnected to the river. New wetlands will give the river and waterfowl more space. Other communities are watching the Atchison County Levee District. They’re waiting to see how the setback helps the community survive future floods before deciding whether it’s a viable option for their own lands.

At Dogtooth Bend, in Illinois, the purchase of wetland easements will soon help compensate landowners who have taken their land out of production. And downriver at the former Mollicy Farms site, Rice and others are monitoring the effects of the restoration and will continue to monitor the Ouachita River water quality in the future. Rice grew up nearby, fishing and swimming in the now-contaminated water. “Nowadays I would never let my little girl do that,” he says of his four-year-old daughter. “But maybe I can help make it safer for future generations.”

Meanwhile, towns and cities along the Mississippi are fighting for legislation that would provide more funding to prepare for future disasters, says Wellenkamp, the Mississippi River Cities and Towns Initiative executive director. But, amid all the floods and the expenses of fighting them or adjusting to them, living and working along the Mississippi River is still worth it for many, he says.

“I still think it’s the most beautiful place on Earth,” Wellenkamp says. “We just have to change our behavior to match it. Gone are the days where we try to change that river for us. It’s not going to work anymore.”

Get the Magazine

Sign up to become a member of The Nature Conservancy and you'll receive the quarterly print edition of the magazine as part of your membership.