Into the Deep

A new way of catching swordfish developed by The Nature Conservancy and its partners could spare other marine species and foster healthier oceans.

Summer 2021

For millennia, people along the Pacific Coast have risked their lives in the open ocean to catch swordfish. Archaeologists have found evidence that Southern California’s Chumash Indians harpooned swordfish at least 2,000 years ago. They and the Chango Indians of Chile’s northern coast immortalized the great fish in rock art and ceremonial headdresses made of swordfish skulls.

Today, the people who continue to fish for swordfish—which can reach up to 14 feet long and weigh up to 1,200 pounds—still have an almost-visceral connection with the animals. Lance Rinehart lives on Catalina Island, off the coast of Southern California. Now 66, he has harpooned swordfish for nearly half a century. Stalking a swordfish while standing atop a “plank” hanging over the bow of a two-person boat can feel more like hunting than fishing, he says.

“I like that adrenaline of being out there; it’s like an addiction,” Rinehart says. “It’s just you and the fish.”

How Swordfish Are Caught, and Why It Can Impact Other Species

Swordfish spend long periods swimming at depth to hunt squid and fish. They will also spend time lazily “basking” at the water’s surface, presumably to warm themselves and recharge after being in deeper, colder water. This is when an experienced harpoon fisher can stealthily approach the fish by boat. Success requires a sure hand and split-second timing. “They can accelerate up to 60 miles per hour in, like, a second,” Rinehart says. “They can be gone in the snap of a finger.”

In contrast to many fish species around the world, Pacific swordfish stocks remain healthy. But as fishers have adopted newer techniques to catch swordfish, marine mammals such as dolphins and whales have been unintentionally caught up in their nets. That has led to increasingly strict regulations, which have driven many fishers out of the business.

In its heyday, the West Coast swordfish fleet spanned the entire length of the coast, running up into British Columbia. Today, the few swordfishers that remain are concentrated in Southern California. The locations and time frames when they can use drift nets (also called drift gillnets) are extremely narrow, and stalking fish one by one with harpoons is a very inefficient proposition for a commercial fisher.

Quote: Chugey Sepulveda

It was like a death of a thousand cuts. Fishers no longer were making very much money because they were forced to operate in a small window.

“I’m the only boat left out of Catalina here,” Rinehart says. “All the guys I used to fish with, there’s not that many of them left. It all just sort of faded away.”

Yet there is still a big appetite for swordfish: Americans eat almost 20 million pounds of swordfish a year. More than 80% of that is imported, and much of it comes from countries in South America and Asia-Pacific that either completely lack or have limited regulations on swordfishing, which results in frequent accidental deaths of sea mammals and sea turtles in those regions.

Finding a Better Way to Fish

But for The Nature Conservancy and its partners, it seemed as if there might be a way to solve many problems at once. “How can you support a thriving fishery off the West Coast?” says Alexis Jackson, fisheries project director for The Nature Conservancy. The Conservancy has been engaging with researchers, local fishers and the agencies that regulate California’s fishing industry to develop more sustainable ways to fish. “We know that the [swordfish] stock is healthy, so it’s OK to harvest swordfish.”

To find a better way, a slew of scientists and fishers would need to study the behavior of swordfish and develop and test a new type of fishing gear. If they succeeded, they could make California-caught swordfish both sustainable and profitable. And even more important, they could export this system to countries where swordfishing has a disproportionate impact on other marine life caught up in drift nets.

How Deep-Drop Fishing Gear Works

Illustrated below--numbers correspond to numbers on the illustration.

Drift Nets Catch Swordfish But Kill Other Marine Life

In California, harpooning was the sole technique for catching swordfish until the late 1970s. By the early 1980s, many fishers had abandoned the labor-intensive, low-yield practice of harpooning and begun using drift gillnets—mile-long nets that hang as deep as 200 feet and are left to float in the water overnight.

But Director and Senior Scientist of the Pfleger Institute of Environmental Research (PIER) Chugey Sepulveda, who has spent more than a decade and a half researching swordfish, says, “It totally backfired.” Scientists and fishers realized that the nets caused a substantial amount of collateral damage. Pacific loggerhead sea turtles, as well as short-finned pilot whales, Risso’s dolphins and other marine mammals, would drown in the nets.

[Text continues below]

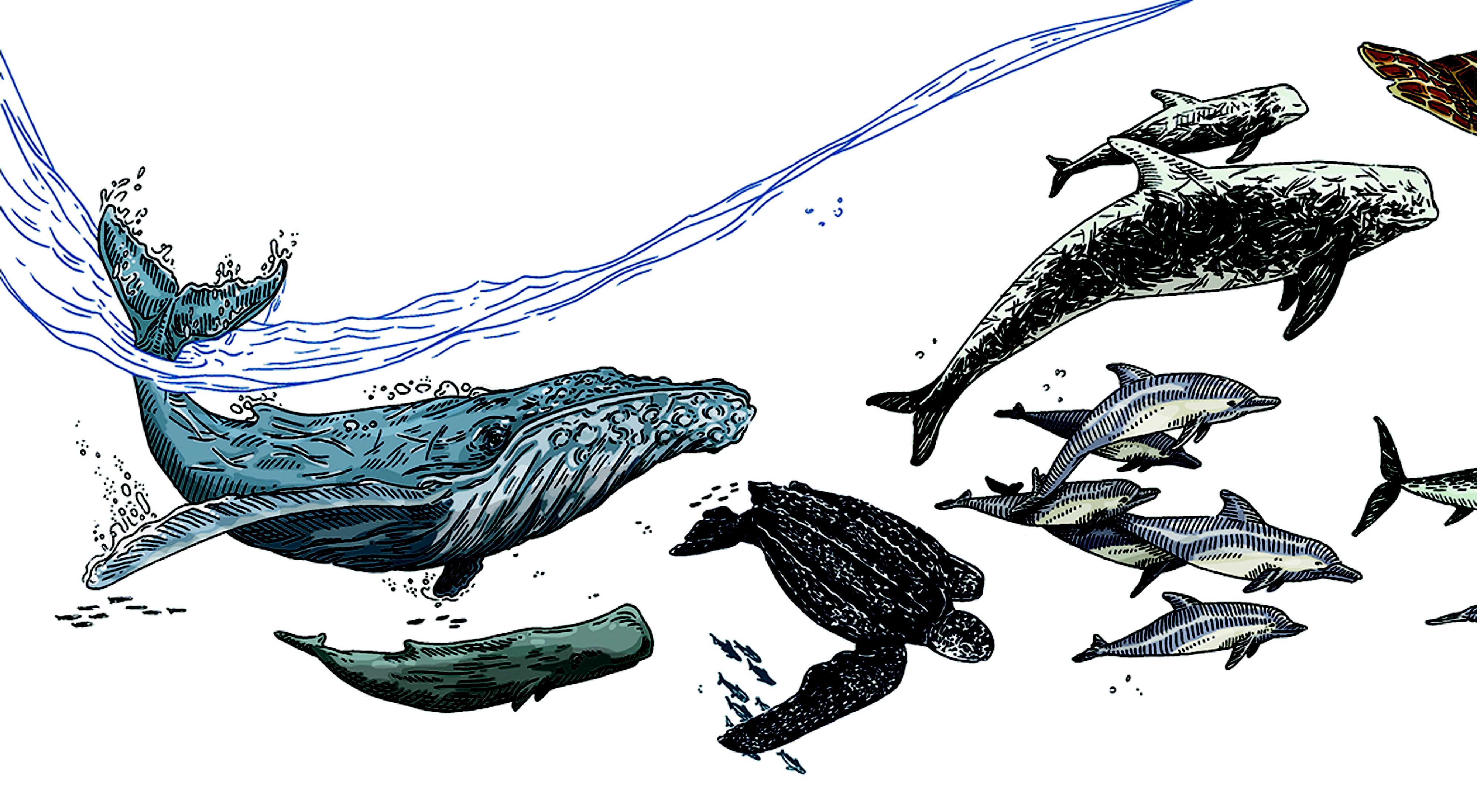

Species of Concern

Many of California’s strict rules on commercial fishing are intended to keep turtles and sea mammals out of the catch.

-

Sperm Whale

Sperm whales, classified as endangered under the Endangered Species Act, can be as much as 60 feet long, weigh 60 tons and dive to over 10,000 feet. While they primarily feed on squid, they’ve also been known to eat sharks.

-

Humpback Whales

Humpback whales eat up to a ton of krill and small fish per day, and migrate up to 5,000 miles. The population that breeds in Mexico but feeds in the Pacific from California to Alaska is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

-

Pacific Leatherback Sea Turtles

Pacific leatherback sea turtles—the largest turtles in the world—can migrate some 7,000 miles each year from Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands to their foraging grounds on the U.S. West Coast and back.

-

Risso's Dolphin

The Risso’s dolphin is a squid- and-octopus-hunting specialist. Its distinctive blunt head is often scarred by the beaks and tentacles of its prey. Some 11,000 to 16,000 Risso’s dolphins live along the U.S. West Coast.

Regulators began closing off more and more of the ocean to protect turtles and marine mammals. In 2001, for instance, the federal government prohibited drift gillnet fishing in 213,000 square miles of ocean off the California coast for three months each year to protect Pacific leatherback turtles, which are classified as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and whose Pacific populations have precipitously declined over recent decades.

For fishers “it was like a death of a thousand cuts,” Sepulveda says. “Once you stacked a ton of restrictions on the fishery, fishers no longer were making very much money because they were forced to operate in a small window.” And the pressure hasn’t let up. Other environmental groups have been pushing the Pacific Fishery Management Council to issue an outright ban on drift nets. That effort has not, as of yet, proved successful. But most fishers, Sepulveda says, understood that “it was time to transition; all the writing was on the wall.”

If swordfishing was to remain viable in California, it would require a completely new line of thinking. The fish would need to be caught in a much more selective manner. But to accomplish that, more had to be learned about this rather elusive fish.

Studying Swordfish to Improve Fishing Methods

Between 2004 and 2006, Sepulveda and other researchers, with support from TNC, began catching swordfish off Southern California, attaching satellite tracking tags to them, releasing them and watching the results. They realized that swordfish off the California coast spend much of the daytime hours hunting squid and fish up to a quarter mile deep.

Sepulveda and the other scientists compared these unique swimming patterns with those of the other sea mammals in the same area. “We realized that there wasn’t a lot of overlap,” Sepulveda says. “Once you get down in the 1,000-foot to 1,500-foot range, there’s almost nothing else down there.”

As the researchers learned more about swordfish feeding habits, they realized it might be possible for fishers to more precisely target swordfish when they are deeper than the other species. The team of researchers modified a similar type of fishing gear that originally had been developed in Florida. Their West Coast version uses buoys to suspend a long, weighted fishing line that runs straight down. At a depth of between 800 and 1,200 feet, the line is outfitted with baited hooks.

Quote

As the researchers learned more about swordfish feeding habits, they realized it might be possible for fishers to more precisely target swordfish when they are deeper than the other species.

Testing the New Fishing Gear

During 2011 and 2012, the members of the research team tested out the new gear, and in 2015 they persuaded the Pacific Fishery Management Council to issue “experimental fishing permits” that allow a select number of fishers to try out the deep-set buoy gear aboard their own boats. That not only helped fishers begin supplying local markets in Southern California with more-sustainably caught fish, but it also helped researchers gather more data about the effectiveness of the new gear.

Rinehart was one of the fishers who tested the experimental gear, and for him, the advantages were clear. “With deep-drop, I get 98% swordfish,” Rinehart says. “It’s very, very little bycatch. Besides harpooning, it’s really the cleanest fishery around.”

Fishers who’ve tried it are adopting the new gear more widely than the science team had anticipated, in part because it’s good business. Since the deep-set buoy gear must be actively tended by swordfishers, their catch is put on ice within minutes of being hooked. This means fishers are bringing a higher-quality product to market. “The quality of the fish, there’s no comparison,” Rinehart says, adding that net-caught swordfish can be dead underwater for hours before being brought up. That difference, in turn, is helping fishers get higher prices per pound. “Deep-drop saved me, that’s for sure,” Rinehart says.

In September 2019, the Pacific Fishery Management Council officially authorized the new gear. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is now working on the implementing regulations, which could allow for the issuance of official permits as soon as next year.

Sharing What We've Learned Can Help Swordfish Populations All Over the World

Swordfish populations span the globe, from the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans to the Mediterranean, which collectively account for millions of pounds of swordfish each year. And, Jackson says, “the conservation threats coming from these countries are actually significantly higher than we see off the West Coast.”

So TNC has started to scale the project internationally. In Chile—which historically has supplied about 10% of the swordfish eaten in the United States—the fishery is 35 times larger than the U.S. West Coast, and it mostly relies on drift-net fishing. According to Jackson, it’s not unusual for Chile’s swordfish fleet to catch up to 700 turtles a year. “Their fleet is up to 700 vessels, where California’s is like 20,” she adds. “And their nets are three times as big.”

A new U.S. regulation on swordfish imports is helping spur change abroad. The Marine Mammal Protection Act Import Provision Rule, which went into effect this year, requires that swordfish imported into the United States be caught in ways that are comparably sustainable to the standards imposed on the domestic fleet.

“The Marine Mammal Act put a very heavy weight on our shoulders,” says Natalio Godoy, the ocean scientist at TNC Chile. “In terms of export revenue, the swordfish fishery is one of the most important fisheries in Chile.”

In March 2019, TNC and PIER took the first steps toward identifying whether the deep-set buoy gear would also work off Chile, by carrying out another tagging survey.

The results found that swordfish near Chile follow movement patterns nearly as deep as the fish near California. A second research project, to refine the use of deep-set buoy gear in Chilean waters, will likely start later this year. The Conservancy is also planning to do satellite tagging on swordfish in Peru, and the lessons learned from the swordfish research could be applied to other fisheries with high bycatch rates.

“It’s hard work, but things are changing,” Godoy says. “A good thing about TNC is our multi-country base, which permits us to build large-scale programs. If we’re working together, we can address problems like this at a global scale.”

Get the Magazine

Sign up to become a member of TNC and you'll receive the quarterly magazine.

Subscribe now