The Healing Power of Trees

Adding 8,000 trees to a neighborhood in Louisville, KY, improves health conditions that are linked to heart disease, stroke and some types of cancer.

Illustrations by Daniele Simonelli | Text by Amy Crawford | Issue 1, 2025

The Watterson Expressway, also known as Interstate 264, is eight lanes wide where it cuts through the south side of Louisville, Kentucky, and for a long time, the only thing separating the area’s single-family homes, parks and churches from all that traffic was a concrete wall.

But today, martial rows of upright arborvitae, a type of cypress often used as hedges, stand guard between the highway and the working-class neighborhoods on either side. These are just a portion of the 8,000 new trees now shading sidewalks and streets, parks and parking lots, front yards and back yards across a 4-square-mile area. Planted between 2019 and 2022, the greenery has transformed south Louisville, roughly doubling the number of trees in an area that had long lacked the leafy canopy found in wealthier parts of town.

The Nature Conservancy and a group of partners, including researchers at the University of Louisville, hope this effort, known as the Green Heart Louisville Project, will also transform how we think about the relationship between nature and human health.

“We all know trees are good for our health—there’s a lot of anecdotal and observational evidence for that,” says David Phemister, TNC’s Kentucky state director. “But there’s not a lot of direct clinical evidence.”

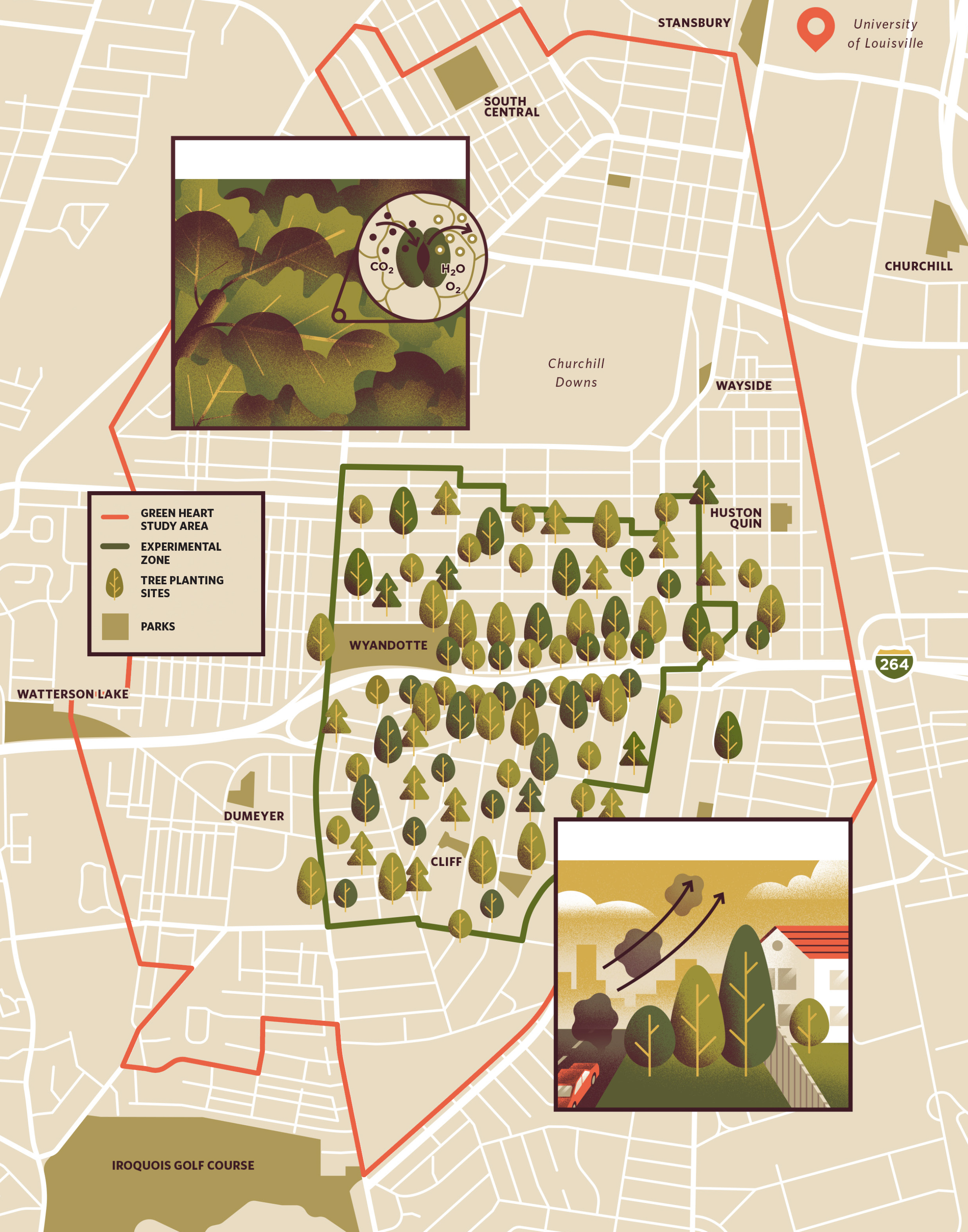

Green Heart

In the fall of 2017, The Nature Conservancy, the University of Louisville's Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute, and other partners launched the Green Heart Louisville Project to examine the link between neighborhood greening and human health. Starting in 2020, TNC and a group of partners began the process of planting about 8,000 large trees throughout part of the study area. The project is tracking the health of 750 residents living near the new greenery compared to those living outside of it. [Click on the headings in the map to learn more.]

Filtering the Air

Tiny pores on the leaves of trees, called stomata, inhale air that contains toxic pollutants such as SO2, NO2, CO, VOCs and ozone. Leaves also filter some particulate matter from the air through absorption and “catching” it on their surfaces. These deposits are washed off by rain and absorbed into the soil.

Redirecting Pollution

Planting trees of gradual heights along the sides of highways creates a barrier that directs air pollution up and away from neighboring homes, while reducing noise pollution. Improving tree density in neighborhoods and around public buildings creates a natural air filter, or “bio filter.”

Until now, that is. Green Heart is the first project to back up the commonsense idea that trees are good for people with rigorous medical research—and the first clinical results, released this past August, are already attracting national attention.

In a way, Louisville is used to the spotlight. The river city of about 600,000 people sits at the center of Kentucky’s vaunted bourbon industry, drawing tourists to its craft distilleries. Downtown, not far from the Muhammad Ali Center (the self-proclaimed “Greatest” was born here), a landmark factory still makes Louisville Sluggers—Major League Baseball’s official bat. And, of course, for 150 years, the city has hosted the Kentucky Derby, one of the most-watched horse races in the country.

Outside of the first Saturday in May, however, the people who live in the shadow of Churchill Downs have sometimes felt overlooked.

“Louisville has a lot of distinctions that are not great,” says Chris Chandler, a Louisville native who directs TNC’s Cities and Strategic Partnerships Program. “We have super-poor air quality. The air pollution is, in some cases, generated from industries and activities in Louisville, but it also moves up and down [the Ohio] River.” Because of the topography, he adds, poor-quality air sticks around longer during the summer.

There’s a direct connection, scientists have long known, between air quality and human health. Polluted air can lead to cancer, heart disease and even obesity. These conditions have contributed to a recent two-year drop in life expectancy between 2011 and 2021. And the harms are not evenly distributed: People who live in more prosperous, predominantly white parts of Louisville live more than 15 years longer than the residents of more diverse, poorer neighborhoods—which, not coincidentally, also tend to have fewer trees.

Daily Dose of Trees

This was the first large-scale study to understand if urban trees could actually improve a community’s health.

Q&A With Dr. Aruni Bhatnagar

Bhatnagar is the director of the Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute at the University of Louisville and the principal investigator on the Green Heart Louisville Project.

You’re a health researcher. How did you come to see nature as a potential medicine?

I started my research working on cardiovascular disease, and it slowly occurred to me that if we were to make significant progress in understanding and preventing heart disease, then we needed to look outside the heart, at the broader picture. At that time, there was a lot of work showing that smoking is bad for your heart, cholesterol is bad and stress is bad, and so on. But more and more evidence suggests that air pollution could also lead to heart disease. So then the question arose, what could we do about that as individuals? I thought, well, maybe one thing to do was to plant trees.

What is the connection between air pollution and cardiovascular disease?

That air pollution can directly increase the risk of heart disease and trigger heart attacks and stroke is very well established, by several hundred studies. When fine and ultrafine particles go into your lungs, they trigger an inflammatory response. We believe that low levels of chronic inflammation contribute to most chronic, noncommunicable diseases like heart disease, cancer, asthma and so on. In cardiovascular disease, low levels of inflammation in the blood vessels form plaques that are sometimes disrupted and give rise to heart attacks and stroke. Whenever you have a spike in air pollution, six hours later you have a spike in heart attacks.

Was there precedent for the idea that trees could help mitigate some of that pollution?

There have been studies that looked at people who lived in green spaces and found they were healthier and lived longer. They were seeing a 10-12% decrease in mortality [over the course of the studies]. That gave us some ground to calculate how much greenness it would take here, and we came to the conclusion that it would take about 8,000 or 9,000 trees over 4 square miles—and very large trees. I had talked to people at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). After they stopped laughing, they said, “Well, if you get the money to get the trees—because NIH is not in the business of buying trees—we might think about funding other things.” That seemed like an impossible task, and we almost gave up! But we were encouraged by The Nature Conservancy.

What are you still hoping to learn?

What we’ve got right now is just a biomarker of inflammation that’s down. C-reactive protein is a very reliable marker, but we’re waiting on measurements of functional effects, such as stiffness of the arteries, anxiety and depression levels, immune responses. And when you do a drug trial, you do a single-site trial, but then in order to get reassuring evidence, you need to do a multicenter trial. So we need to do this in many different cities.

Such disparities have long troubled Dr. Aruni Bhatnagar, chief of the Division of Environmental Medicine and director of the Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute at the University of Louisville. He was aware of the longstanding associations between greenery and human health, and of the ability of plants to mitigate air pollution, including by serving as a physical barrier against dirty air, absorbing chemicals into their cells and even collecting particles with their leaves, in the same way that insects are trapped by flypaper.

Still, the connection between greenery and health had only ever been demonstrated by observational studies. Randomized controlled trials are generally accepted to be the gold standard in medical research. Most pharmaceuticals on the market have multiple such studies behind them. So Bhatnagar intended to treat nature like medicine.

“The best way to do it would be to plant trees and then see what happens,” Bhatnagar says. “That’s the clinical scientific methodology. The trees are the treatment.”

It was a simple idea, but the logistics would prove more complicated. Bhatnagar realized that, to make a significant difference over the limited time that could be allotted to a clinical trial, the research team would have to plant very large trees, not saplings. And they would need a lot of them.

Planting trees may be an unorthodox clinical intervention, but it was in the wheelhouse—and the budget—of The Nature Conservancy, which over the past decade has been conducting more work in cities, places where the well-being of nature and humanity intersect in clear ways. That’s sometimes been about ensuring clean water or air, or safeguarding habitat. Here, the goal would be improving people’s health.

“We are an imperiled species,” says Chandler, who helped lead TNC’s involvement in the collaboration that became Green Heart. “We are just as important as any other system or any other species on the landscape, and humans need to see ourselves in the work of healing and restoring our planet.”

The project began with community engagement, as the local nonprofit organization Louisville Grows worked to ensure that people wanted trees in their yards, and that they would do their part to help care for them. Many residents were excited; community groups had after all been working for years to get more infrastructure investment, including in parks and street trees. Others expressed less enthusiasm about watering and raking leaves, or disbelief that the trees were actually free.

Planting an Instant Canopy

The Nature Conservancy led the effort to plant more than 8,000 large trees across a 4-square-mile neighborhood.

Q&A with Chris Chandler

Born and raised in Louisville, Chandler directs The Nature Conservancy’s Cities and Strategic Partnerships program, and he helped lead TNC’s work on this study.

Planting trees seems simple, but the logistics here were actually pretty complex. Can you explain?

National Institutes of Health funding is a five-year cycle. They gave us an extra year because of the pandemic, so we had six years to show a difference. We didn’t have the luxury to plant trees and sit back for 10 or 15 years, let them grow, then see. We had to move very quickly. The largest trees we planted were 30-plus feet tall—the total mass of these trees was 2,000 pounds.

When we think of urban trees, we generally think sycamores, maples, oaks and elms. Why did you plant mostly evergreens?

Trees are a mechanism to improve specific pollutants in the air, specifically volatile organic compounds and ultrafine particulate matter, PM 2.5 and finer. That’s the stuff coming out of tailpipes. Trees absorb it into their pores, or it could just stick on the leaves or the needles of trees. That means trees that have rougher or stickier surfaces capture more air pollution. Trees also disperse air pollution, so if you plant them together in a tight configuration, air pollution gets disrupted and is pushed up into the atmosphere, instead of settling on neighboring homes. Evergreen conifers are better at doing all of that. They have more biomass, they have a 360-degree surface area on their needles, and you get four-season efficacy.

It was certainly a dramatic change in the level of greenery, but were you surprised by the impact it appears to have had on people’s health?

We were completely blown away. First, I was incredibly proud that the research strategy held up under all of the factors that could have thrown it off course. TNC is not normally used to working with health researchers—we all have different languages. It was not easy to cocreate an interdependent research strategy that actually worked. That is huge. And then the fact that the initial findings showed such a statistically significant influence on health—it was like, “Oh my, holy cow!” Maybe we had dreamed that something like those findings could have been reality 10 or 15 years down the road. It’s jaw-dropping.

What does Green Heart mean for the people of south Louisville?

I’ve observed more social and community cohesion. Drive through and you see Green Heart yard signs, green ribbons tied on trees and things like that. People are proud of these trees, and they’re proud that they’re part of something groundbreaking. The emphasis is still on their community, their families, but also, “Wow, this is bigger than us!” We can begin to be a role model for other communities around the country, and around the world, in advancing the science-based approach to nature-positive solutions in cities. That’s very cool.

“We spent a lot of time knocking on doors and sitting on front porches,” Chandler says. “It’s conversations like that where you build trust, you build understanding.”

Meanwhile, Bhatnagar’s research team recruited about 750 people, both from the treated neighborhoods and from a control area south of downtown Louisville, who would have their health monitored before and after the trees arrived.

Then, in 2019, volunteers and contractors began planting.

“We planted trees in every typology that you could find in the city,” Chandler says. “We planted them in parks, on private property—backyards, front yards. We planted them all the way from the neighborhood street to arterial roads to the federal highway. We planted in church parking lots, at community centers, even a couple commercial properties like gas stations.”

Jerry Englehart, a social worker who lives two blocks from the expressway, accepted more than two dozen trees on his .11-acre lot, including a handsome, flowering yellowwood in his front yard and a row of arborvitae out back. The difference has been remarkable, he says, noting that traffic noise is down, while more birds have come to roost as the trees grow.

“It’s really nice to be able to go into our backyard and be in a green space, without having to drive somewhere,” he says. “We can just go out there and get green therapy.”

Englehart and his wife, who recently welcomed a baby daughter, also signed up for the health study. “I think research is important,” Englehart says, “and to be able to participate in this, it makes me feel like I’m actually contributing in a way that’s helping.”

Quote

Already other cities are beginning to look to Louisville as a leader in connecting urban greenery with human health.

This past August, the research team at the University of Louisville reported their first results. Within the treatment area, where homes are now surrounded by more than twice as many trees, study participants had significantly lower levels of a blood marker known as C-reactive protein, which is a strong indicator of inflammation.

Part of the body’s natural defense system, inflammation is triggered by injury, infection or irritants, summoning immune cells to combat pathogens and heal damage. But so-called chronic inflammation, which lasts for months or years and is associated with ongoing exposure to irritants like cigarette smoke and air pollution, actually degrades the body’s functions and contributes to problems like cardiovascular disease, diabetes and some cancers. The 13-20% reduction in C-reactive protein the Louisville researchers found translates to a proportionally lower risk of these inflammation-associated conditions.

It’s great news for residents of the newly green neighborhoods, and an astounding finding for the research team.

“It was hard to convince ourselves!” Bhatnagar says. “Certainly we didn’t expect this, within such a short time.”

There’s plenty more to learn, Bhatnagar says, cautioning that the dramatic drop in inflammation levels, though heartening, is still just the first result. The researchers are continuing to track participants’ health, including effects on blood pressure, immunity and mental well-being. Other studies are looking at environmental effects, such as how the trees have affected air pollution, temperature and biodiversity.

Meanwhile, Bhatnagar is fielding calls from researchers at other institutions hoping to replicate the Green Heart findings. And already other cities are beginning to look to Louisville as a leader in connecting urban greenery with human health. That’s been a source of pride for this city by the Ohio River, as well as for everyone involved with Green Heart.

“Until we got these first results, I’m sure there was continued skepticism out there,” says Phemister. “But seeing those initial results, and how quickly this showed up in the data, was a real eye-opener. Think about the billions of dollars that are invested in our road systems, in our utility systems—all essential, all important for human communities. Nature needs to be a part of those investments, too.”

“Nature is critical infrastructure in cities,” he adds. “And its conservation could be a key public health strategy.”

About the Creators

Amy Crawford is a freelance writer based in Michigan who writes about the environment, history and art for publications like Smithsonian and Slate.

Daniele Simonelli is a freelance illustrator based in Rome. He is the founder of a studio collective of animators and illustrators from across Europe.

Magazine Stories in Your Inbox

Sign up for the Nature News email and receive conservation stories each month.