The Age of Nature

How we choose to live with nature will determine our future.

Explore humanity’s relationship with nature and wildlife, as scientists and conservationists from all over the world examine ways we can restore our planet.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE SERIES ON PBS ›

“How we live with nature now will determine our future.”

This line, from the opening sequence of the documentary series The Age of Nature, underscores the complex, interdependent connection between people and nature that persists today.

The three-part series, produced by Brian Leith in consultation with The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and airing on PBS, demonstrates how much we rely on the natural world, how we’ve changed it—and how our ability to change our relationship with nature today could determine our survival.

Too often nature is presented either as a far-off place untouched by humans, or a victim of human predations. It’s wolves stalking prey through a stark landscape, or a polar bear floating on fragments of a rapidly melting ice sheet. Rarely do we bear witness to stories of humanity thriving with nature—or of the consequences that humanity faces when we fail to ensure that the rest of nature thrives alongside us.

But while it’s true that human actions can degrade the planet, it’s equally true that we can restore it. Species can rebound from the brink of extinction; bare landscapes can be reforested and fragmented rivers reconnected. TNC is working with communities around the world to protect and restore the natural landscapes that they—that we all—depend on.

Indeed, we are learning that nature is incredibly powerful and resilient. And while we face unprecedented challenges today to protect nature, as The Age of Nature shows, our place on a further-degraded planet should be equally worrying. What we choose to do now, how we live and work with nature, will determine humanity’s future.

Episode 01: Awakening

A new awareness of nature is helping to restore ecosystems

We like to think of humanity as independent and innovative; the human spirit forging the way for societal evolution throughout the centuries. Yet so many of the technologies we create are essentially replicating what nature gives us for free.

Abundant food, clean air and water, a temperate climate—these essentials of human life are the product of nature’s complex engineering. But because these things are free, too often we take them for granted.

There’s perhaps no better example than how we’ve treated the ground beneath our feet. The industrial farming practices developed to feed growing populations have degraded the health of our soil in ways that impact both wildlife and food production.

But adopting regenerative practices, like reduced or no-tillage planting and the use of cover crops, can restore the complex soil biology that’s key to long term crop production—while also reducing greenhouse gas emissions and nutrient runoff. It’s a win for farmers, for wildlife and for the climate.

Quote

At this point it’s not enough to just produce food in ways that minimize harm to the planet—we must start producing food in ways that actively restore the health of the planet.

What Next?

Learn more about these issues and how you can engage with our work.

Discover how a new awareness of nature is helping to restore ecosystems from Panama to China to Mozambique.

Meet food producers using regenerative farming at the heart of their practices to tackle climate change and restore nature with regenerative outcomes.

See how you can help.

Get our guide to impact investing one of the most sustainable—and fastest growing—food sources.

Episode 02: Understanding

A new understanding of nature is helping us find surprising ways to fix it

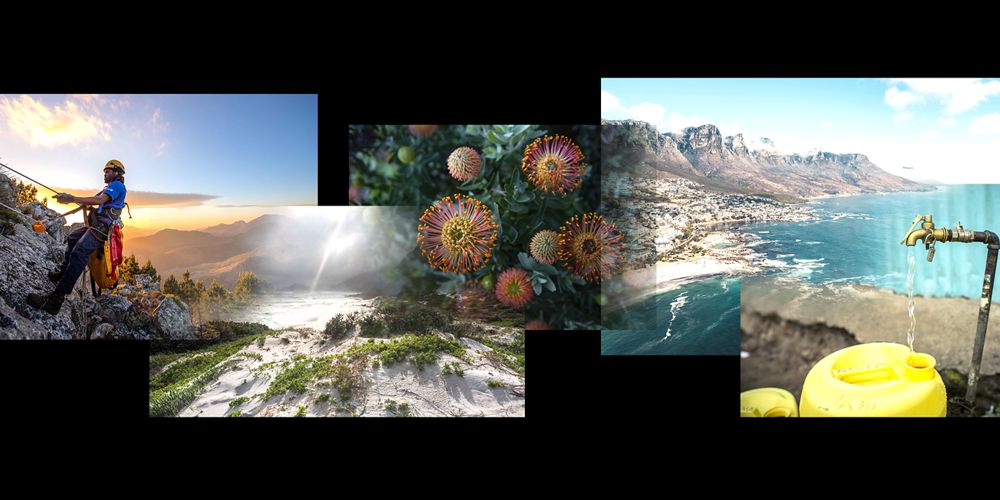

When Cape Town, South Africa faced the prospect of taps running dry in 2018, the culprit was not drought alone—thirsty invasive trees, originally introduced to provide timber, were draining the aquifer that the city relies on for its water supply. Removing invasive species and restoring the natural watershed landscape has ensured more reliable water flows.

This is just one example of a “water fund”—investments in the conservation and restoration of landscapes that filter the water used by communities downstream.

Another example of this model can be seen in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where the Rio Grande and its tributaries supply water for 1 million people—nearly half of the state’s population. In recent years severe wildfires and subsequent erosion filled the river with ash and sediment, causing water treatment disruptions. By restoring forest land upstream, downstream communities benefit from reduced fire risk, better water quality, and a healthier habitat for fish and other wildlife.

Quote

Replacing a single acre of invasives with native fynbos would save more than 85,000 gallons of water annually.

What Next?

Learn more about these issues and how you can engage with our work.

From the Pacific Northwest to Yellowstone to Scotland, scientists, citizens and activists are restoring the environment, benefiting humans and animals alike.

See how humans reshaped the planet—and how we might do so in the future.

See how you can get involved.

Climate change will exacerbate water security challenges. See how nature-based solutions can help water-stressed regions adapt.

Episode 03: Changing

Discover why restoring nature might be our best tool to slow global warming

No matter how beautiful and green, a lone tree can never be a forest; and likewise, a single country cannot solve climate change. Even Bhutan, the world’s only carbon-negative country—where dense forests absorb more greenhouse gases that the nation emits—is not safe from the threats posed by the changing climate.

Challenges like climate change and biodiversity loss are complex and global in scale—and so are the solutions that are required. Yet even as temperatures rise, many countries continue to clear or degrade their natural lands; in 2016 alone, 29.7 million hectares of forests were cleared—an area the size of Italy.

The 2015 Paris Agreement set a global goal for tackling climate change, but reaching this goal will require increased commitments from every country on the planet.

But while no country can stop global warming alone, Bhutan is among those that are demonstrating how it can be done.

In fact, protecting and restoring forests, wetlands, grasslands and other habitats could provide up to a third of the emission reductions needed to prevent catastrophic temperature increases.

Increased investment in these natural climate solutions, along with an accelerated transition to a carbon-free economy, offers our best opportunity to realize a future where people and nature thrive.

Quote

Bhutan is the only country in the world that absorbs more carbon than it produces—achieved by looking after nature.

What Next?

Learn more about these issues and how you can engage with our work.

From Borneo to Antarctica, the resilience of the planet is helping us find solutions to cope and even mitigate climate change, providing hope for a more positive future.

We need $700 billion to save nature—this is how we can get it.

The answer is 'yes,' with some big 'if's. Take action on climate change now.

Accelerating climate ambition in the next year is critical—here’s a playbook for action.

The Way Forward

2020 was supposed to be a "super year for nature," with important new agreements to halt biodiversity loss and hold nations accountable for climate goals.

The COVID-19 pandemic has delayed those discussions—but that doesn’t mean we can’t take action. If anything, the global pandemic has further showed how intertwined and dependent we are on nature—and that while tackling big problems collectively is extremely difficult, it IS possible.

Indeed, there are new signs of hope—more than 70 nations have now signed a 10-point pledge to halt the destruction of nature. Perhaps this is also the sign of renewed understanding that the future of humanity depends on our ability to live with nature—that, in fact, we are central to this Age of Nature.

Global Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.