Panther Culture: Lost and Found

Though most Floridians will never see a Florida panther in the wild, taking pride in their elusive state animal is key to its survival.

Cougars. Wildcats. Pumas.

The words may strike up an image of a big cat roaming the mountainous western United States but in the eastern U.S. they’ll most likely conjure up an image of a high school football team.

Far from the mountains of the West, Floridians are the only people within a thousand miles who can actually claim to live among a population of these big cats.

Here in Florida, they’re called panthers. They’re the official state animal. And yet, there are still many residents who don’t know what the elusive predators look like.

“There’s no such thing as black panthers. Those are leopards and jaguars,” says Ricky Pires, affectionately known as “Mrs. Ricky” by the thousands of Florida elementary students she educates each year. “Carolina Panthers [the North Carolina-based NFL team] are black, but that’s not real. That’s why they’re not winning.” (At the time of the interview, the Carolina Panthers were 0-2).

Florida panthers are everywhere and nowhere

Beyond knowing its coloring, there’s the active exercise of remembering they’re even there. An animal as elusive as the Florida panther doesn’t do a lot of self-advertisement.

Two ways to be reminded at all of its existence are to follow the NHL’s Florida Panthers (Miami’s pro hockey team, featuring the more accurate tawny coloring) or to drive along roads in panther country and see the yellow crossing signs.

Just like how the real Florida panther was never completely lost even in its most meager years, symbols of the cat show up throughout the state if you keep your eyes and ears open. The panther can appear on a mural in town or as a tattoo on someone’s shoulder. It also plays an important role in a creation story of the Seminole Tribe in Florida, in which the panther is the first being to walk the Earth.

As recently as 30 years ago there may have only been a dozen walking the Earth.

“They weren’t part of my world”

Inclusion on the federal Endangered Species list, human intervention to deepen its gene pool and land conservation by groups like The Nature Conservancy have brought the big cat back to around 200 animals.

And with numbers seemingly going in the right direction, there’s plenty of education needed for a Florida that’s growing in population, often because people are relocating from other states.

“Typically the message you hear around rare animals is that they just keep on going down,” says Tim Tetzlaff, conservation director at the Naples Zoo. “This is an animal who's actually in an upswing, so fundamentally, people need to know we're in a new era of panther conservation.”

Even for longtime Floridians this is a change. Tetzlaff grew up in the state at a time when there may have been as few as 10 left in existence. They simply were not part of his world growing up.

Panther Posse to the rescue

The Florida youth of today are in a different place and programs exist to acculturate them to their furry neighbors.

“Most of the kids who come here do live in panther habitat,” says Pires. “So they learn how to coexist with them.”

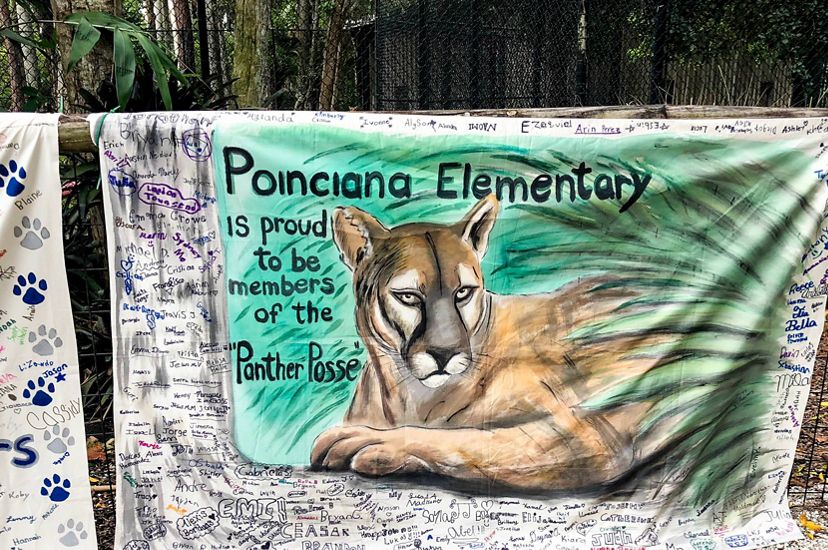

Pires is the founder and director of Florida Gulf Coast University’s (FGCU) Wings of Hope program, which connects 450 FGCU students with more than 5,000 4th and 5th graders each year. They arrive on campus in their “yellow limos” (school buses) and participate in a program called Panther Posse.

Panther Posse helps students understand their state animal on their own terms. “With approximately 150-200 panthers out there, that’s about the size of their 4th grade. It’s very powerful for them to make that connection,” says Pires.

The students can make a difference right away by educating a parent or raising funds for camera trap research (Pennies for Panthers), but the true power of Pires’ program lies further into the future.

“If people don’t understand it, they’re not going to vote to save its habitat,” says Pires. “They’re the future of the Florida panther. Some of these children could be our governor, right?”

“The panther is their panther”

Florida panther advocates are already out in force and their energy can mean a lot at this critical time in the protection of their corridor. Wendy Mathews, TNC’s conservation projects manager in Florida, attended a public comment period about a proposed toll road plan that could cut through the heart of panther habitat. She was inspired by the many commenters who had never seen a panther in the wild yet eloquently represented the panther’s habitat needs.

“The panther is their panther. It's their state animal, it’s a symbol of natural Florida, a symbol of a healthy environment and ecosystem,” said Mathews. “I felt they had an ownership of it and a responsibility for ensuring its survival.”

Quote: Ricky Pires

Some of these children could be our governor, right?

Panther supporters also show up in numbers to the Naples Zoo, which houses a Florida panther abandoned at birth and also runs an annual Panther Festival. Tetzlaff acknowledges that while he's thankful for the people who show up for every panther-related event, it's the rest of the region that he'd like to reach.

Urge Congress to Act

Without strong funding for LWCF, habitat protection for the panther is in jeopardy.

Help Save PanthersThat’s why the zoo moved the festival to one of its free Saturdays: to encourage more people from across the urban-rural divide to get acquainted with their “new” neighbor.

It will be a different experience for people on farms versus people in condos. Afterall, people who raise livestock will sometimes need to deal with panthers preying upon their animals. Tetzlaff dreams that one year, folks at the Panther Festival will give a hand for the ranchers out there whose bottom lines are tested by the panther’s appetite.

Across all walks of life in Florida, a little more understanding about this lost and found state animal can make people’s lives better everywhere.

As Mrs. Ricky Pires tells all the future governors in the room, “When you save the Florida panther, you’re going to save clean water and clean air, so we're also saving ourselves.”