People on the Water: Power and Permanence on the Great Bear Sea

A new agreement conserves 10 million hectares of globally rare marine habitat while supporting Indigenous-led stewardship and sustainable economies.

A grizzly bear is walking by her house, causing her dog to bark at the window. Dani Shaw is unphased.

We continue talking potatoes.

Shaw is the elected Chief Councillor for Wuikinuxv First Nation, a people who’ve lived along the Central Coast of Canada’s British Columbia for tens of thousands of years. She’s also a mother of three and the co-owner of her remote community’s only water taxi.

Access to groceries is extremely limited and expensive for the Wuikinuxv (pronounced Wee-Kunn-Oh), whose main village is unreachable by road. They’ve long relied on flying in goods, which, with the price of freight, can drive the cost of a bag of potatoes upwards of CDN$30.

"We should be golden"

Shaw’s water taxi can shuttle in groceries cheaper than a plane can, but it’s still a three hour boat ride to Port Hardy, the closest large town.

That’s not always feasible, and it shouldn’t be necessary. The Wuikinuxv’s primary grocery store really should be the water beneath the boat.

“Living where we do, we should be golden,” says Shaw, who previously directed marine use planning and stewardship for the Nation. “There should be no problems growing and harvesting our own food and living practically off-the-grid.”

More stories and insights in your inbox.

Get our latest updates from around the world of nature.

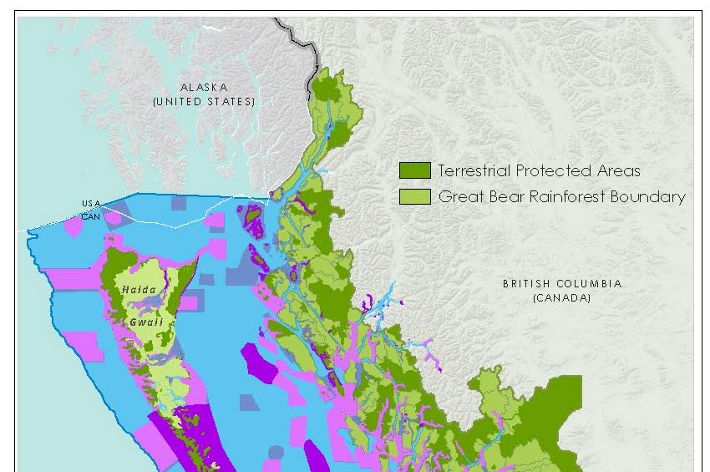

Get our newsletterThe Wuikinuxv live on the Great Bear Sea, a vast medley of marine habitats such as dense kelp forests, lively estuaries, and large coral beds stretching from the northern tip of Vancouver Island up the coast of British Columbia and west to the islands of Haida Gwaii.

Its diverse habitats form one of the most productive cold-water ecosystems in the world, drawing together endangered whales, halibut, abalone and, yes, bears.

For tens of thousands of years, First Nations have stewarded these habitats with care and balance, sustaining themselves on harvests of herring, crab, eulachon, seaweed and more.

But a legacy of colonial policies that led to overharvesting and mismanagement disrupted this balance, reducing stocks of culturally and nutritionally and economically-important fish to all-time lows.

First Nations along the coast did not sit idly by. They needed a healthy and thriving Great Bear Sea, and knew the world did too.

“If we take care of the land and the water, it’ll take care of us,” says Shaw, reflecting a belief shared among Indigenous leaders in the region.

Those leaders never stopped dreaming.

History in the making

On June 25, 2024, 17 First Nations, the Government of Canada and the Province of British Columbia launched the Great Bear Sea Project Finance for Permanence (PFP) to support long-lasting protection for the Great Bear Sea region and sustainable economic development across its communities.

The historic initiative secures long-term funding to protect and improve the management of more than 10 million hectares (25 million acres) of marine habitat.

That’s an area comparable in size to Lake Huron, Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined.

PFPs are the most powerful tools the world has to protect nature at the scale of entire ecosystems. They create the conditions for long term success by finalizing multiple agreements in a single-close moment. Notably, this PFP:

- Creates a co-governance agreement between Indigenous and non-Indigenous governments to implement the world’s largest Indigenous co-designed marine protected area (MPA) network.

- Brings together CDN$335 million (US$243 million) from the federal government, provincial government and private donors (including The Nature Conservancy) that’s projected to create 3,000 jobs and deliver an additional CDN$750 million in communities across the region.

'People on the water'

As impressive as the numbers are on paper, what makes the PFP such a significant step towards realizing the dreams of so many First Nation leaders is its commitment to follow-through on the water.

Creating a network of MPAs, especially one endorsed by multiple governments, is no small feat. But ensuring that there's money to actively carry out this marine protection is a formidable hurdle of its own.

“Lines on a map don’t protect territories, people on the water do,” says Shaw in a video about financing marine management.

With long-standing stewardship traditions and place-based knowledge, First Nations of the coast are uniquely positioned to restore this complex ecosystem.

The Great Bear Sea PFP establishes stable, long-term funding for First Nation-led stewardship, bolstering efforts such as Indigenous Guardian programs to restore fisheries, safeguard habitats, protect cultural resources and provide food security.

Dedicated funding is huge for Guardian programs all over the coast. “We have six Guardians," says Shaw, who wants to see that number increase to adequately monitor their marine territory for illegal activities, climate impacts and other changes.

She wants to make sure "we can have as many eyes and ears on the water as possible.”

Then, there are repairs and preventative maintenance for the Wuikinuxv’s two patrol boats. Motors need to be replaced every few years at the minimum cost of CDN$25-30,000.

There are additional costs for trainings in vessel operation and first aid, maintenance for Guardians’ cabins, rain gear and more. “It just all adds up.”

The funding doesn’t just increase capacity for stewardship programs; it can transform their scope from reactive outreach to the proactive, holistic First Nation-led stewardship they were always meant to be.

“We're able to look at these dollars and go, ‘Where can we really make this money work as hard as it can possibly work based on the information that we have at hand, the resources we have at hand, the people we have at hand,” says Shaw.

“And we can really get out there and make the most impact that we possibly can within our territories, which then feeds into the larger ocean, which then feeds into global targets of 30x30. And so, any work that we do ultimately impacts the rest of British Columbia, Canada and the world.”

Roots from the rainforest

One doesn't need to travel far from the Great Bear Sea to find an example of what success could look like. Intertwined with the sea is the neighboring Great Bear Rainforest, home to the world’s first working PFP model.

In 2007, the Great Bear Rainforest PFP established co-governance and secured long-term financing for conservation of 6.4 million hectares (15.8 million acres) of coastal temperate rainforest home to ancient cedars, coastal sea wolves and spirit bears, a subspecies of black bear with a recessive gene of pure white fur.

Over the past two decades, First Nations of the Great Bear Rainforest and Haida Gwaii helped found an Indigenous-led conservation finance organization called Coast Funds, develop 18 Guardian programs and create roughly 1,300 permanent jobs.

“You’re not done yet. We’re marine people.”

Dallas Smith played a role in getting that groundbreaking rainforest agreement to the finish line. The feat earned international acclaim, and so Smith expected a similar congratulatory response when he met with members of his community.

Their words humbled him and kept him focused on an even bigger challenge. Smith, now the president of an alliance of First Nations called the Na̲nwak̲olas Council, recalls the wisdom his community shared with him back in 2006.

“They said ‘You’re not done yet. We’re marine people. Our marine environment is the same as our terrestrial environment. It’s holistic, and it’s together.”

First Nations of the region, including Smith’s community, didn’t settle for protection that ended at the water’s edge. They kept leading towards their vision of sweeping protection across land and sea.

To make the eventual marine deal the best it could be, First Nations continued to invest in the success of the Rainforest PFP, gaining valuable lessons and confidence along the way.

With that confidence, as Smith described at the 2024 launch of the Great Bear Sea PFP, “people started investing in our dreams as Indigenous People of self-determination and reconciliation.”

Another huge benefit of the original Rainforest PFP, as Shaw points out, was that First Nations grew their collaborative muscles.

“The relationships that were built amongst the Nations have really been what’ve brought us to today.”

Our role

At the request of First Nations, we've contributed long-term investment, including science, fundraising and communication support to this initiative.

For nearly two decades, The Nature Conservancy and our Canadian affiliate Nature United have supported an Indigenous-led vision of conservation, co-governance and sustainable economic development in the Great Bear Rainforest and Sea.

Explore how we partner with Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities around the world.

The long game

Every detail of the Great Bear Sea PFP revolves around that second P in PFP—permanence.

Permanence is 3,000-plus new, permanent jobs, such as GIS planners, Guardians, shellfish growers, tour operators, vessel maintenance techs and bakers to feed them. Shaw’s 17-year-old son has started working with the Nation’s fisheries department, counting sockeye salmon with sonar.

Permanence is 33,000 days worth of valuable training in first aid, marine safety, archaeological surveying, cultural knowledge, leadership and more.

Permanence is a return to balance for food chain-sustaining habitats like eelgrass, spongebeds and kelp forests so that nutritent-dense eulachon fish can run up the inlets of the Wuikinuxv and other First Nations once again.

And less reliance on $30 bags of potatoes.

"We're always playing the long game,” says Shaw. “When we when we talk about ‘long term sustainable,’ we're not talking about ten years. We're talking about a hundred.”

And in a game where a seamless ecosystem of sea and rainforest sees renewed health and restored balance, the whole world wins.

The latest from Great Bear Sea

For more news and updates from the initiative, visit the Nations' website: ourgreatbearsea.ca

Help Breakthroughs Break Through

The climate and biodiversity crises are interconnected and daunting. But by working together, we can overcome the barriers to the solutions our planet needs. Get our monthly newsletter and join a community of changemakers.