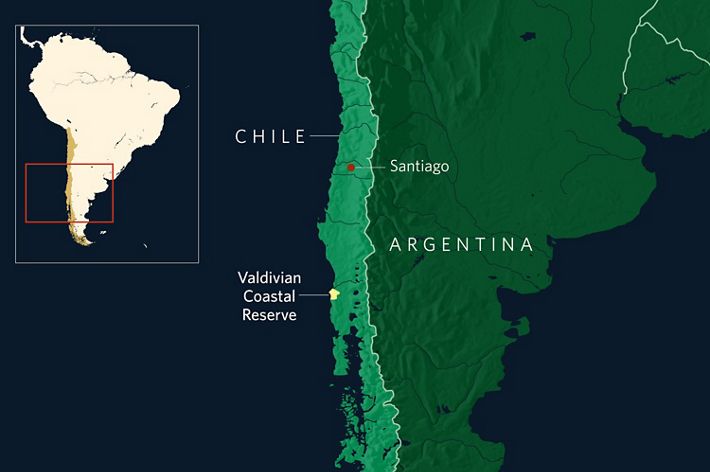

Breathing New Life into Chile's Valdivian Forest

Forest carbon opportunities help local communities protect Chile’s ancient forest.

This story is part of our Living Carbon series, covering the power of natural climate solutions for communities, biodiversity and the planet. > Explore the Living Carbon stories.

When a logging company went bankrupt, a new kind of economy flourished between the ancient coastal rainforest of southern Chile and its Indigenous tribes. A collaborative conservation effort saved one of the world’s last large swathes of temperate rainforest, avoided the release of more than 500,000 tons of carbon emissions, created a conservation-focused local economy complete with new jobs and opportunities and protected one of the oldest trees on Earth. But this future was not always so certain.

The story of Chile’s Valdivian Coastal Reserve (VCR) begins back in 2003. When an industrial timber company filed for bankruptcy, the Cordillera Pelada Mountain Range was put up for auction. One of its largest potential buyers planned to continue the country’s century-long trend of cutting down ancient trees to clear the way for eucalyptus plantations while destroying even more lands for a coastal highway expansion.

Stay in the Loop.

Get local conservation news and stories delivered right to your inbox.

But The Nature Conservancy, with support from the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Conservation International, was able to purchase the property’s debt to create a nearly 125,000-acre protected area of temperate rainforest. TNC cancelled and permanently retired the permits that allowed for the ongoing conversion of native forest to exotic plantations and donated part of the protected area to the Chilean government, and connected the landscape to the Alecerce Costero National Park, home to the nearly 5,500-year-old “Alerce Milenario,” which may be the oldest tree on Earth.

An Innovative Way to Fund Conservation and Community Priorities

Thanks to its old growth forests and dense biodiversity, the Valdivian Coastal Reserve’s trees can store more than 800 metric tons of climate changing carbon dioxide per hectare, one of the highest rates in the world. This potential made the region an ideal candidate for Chile’s first Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) forest carbon project, an effort to enhance the area’s potential for both avoiding emissions associated with deforestation and sequestering and storing carbon.

Located in a 1,273-hectare area within the reserve, the VCR carbon project became the first REDD+ project in Chile to have its carbon credits verified by the globally recognized Verified Carbon Standard organization (today known as Verra). Verified Carbon Standard audits over 2014 and 2015 confirmed that the project’s actions to prevent further deforestation had avoided at least 533,654 net tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions between 2003 and 2014—equivalent to taking about 114,000 passenger vehicles off the road for a year.

Quote

In total, between 2003 and 2014, the greenhouse gas emissions avoided by the project are equivalent to taking about 114,000 passenger vehicles off the road for a year.

The Value of Natural Climate Solutions

A recent assessment by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) names ecosystem restoration as one of the top five most cost-effective climate actions we can take by 2030, and deforestation is the single largest driver of emissions from land-use change. That’s why the Paris Climate Agreement states that countries should protect and enhance their forests to create carbon ‘sinks’, like the Valdivian Coastal Reserve, to limit global warming to no more than 1.5°C and avoid catastrophic climate change.

At this moment of climate crisis, we need every tool in the toolbox, including rapid decarbonization of energy and transportation systems, as well as harnessing the natural carbon storage power of forests and other carbon rich ecosystems. If scaled up now, natural climate solutions could provide up to a third of the emissions reductions needed to reach global climate goals by 2030. What’s certain is that we cannot achieve the 1.5°C target without nature—without both protecting our remaining forests and restoring our damaged land and seascapes.

The Forest’s Beating Heart

The Valdivian Coastal Reserve contains more than just awe-inspiring old-growth trees. At its heart are the people who care for the ecosystem and depend on its health for their own livelihoods—people like Margarita Huala. A local Indigenous leader, Margarita believes the most important benefit brought by the creation of the reserve is the flows from the rural water project that brought clean, reliable drinking water to the nearby towns of Chaihuín and Huiro, as well as the influx of tourism for the local economy.

For local Indigenous leader Margarita Huala, the most important benefit of the Valdivian Coastal Reserve is the healthy land’s ability to filter and carry clean drinking water to nearby towns.

The VCR project helped Margarita to set up a small business with other women in the community. They began by selling empanadas out of a wheelbarrow and gathering non-timber products from the forest, before opening a local restaurant that thrived until the Covid19 pandemic.

Faced with the tourism restrictions, Margarita’s family started a cooperative to develop alternative ways to generate income, and her husband and children have also found work in the reserve, fixing fences and improving the bridges, trails and walkways used by both the community and tourists. Margarita hopes to see even more local jobs generated, especially during the winter months—and to get the restaurant up and running again. But she already believes that the project has “helped us, as leaders, to defend things that we did not do before.”

“Without the reserve, I think it would be destroyed because before the forestry companies were just logging and logging. They cut down and burned the native forest. They did not even give firewood to hospitals or homes. It was all destruction. It is better to have The Nature Conservancy here because their word is to protect. They preserve what is left, or what they can save—animals, birds, everything.”

Our global insights, straight to your inbox

Get our latest research, insights and solutions to today’s sustainability challenges.

Sign UpBreathing New Life and Opportunity

All the earnings from selling carbon credits are reinvested in the forest to bring new life and possibilities to its nature and communities. Since 2014, US$ 3.2 million has been raised from carbon credit sales and used to advance the project goals, including forest restoration and replanting native species to protect biodiversity and carbon stocks; as well as improving the well-being of local communities through sustainable livelihoods, water and sanitation, marine protection and artisanal fisheries, women’s empowerment, strengthening local access and resource tenure, and environmental education.

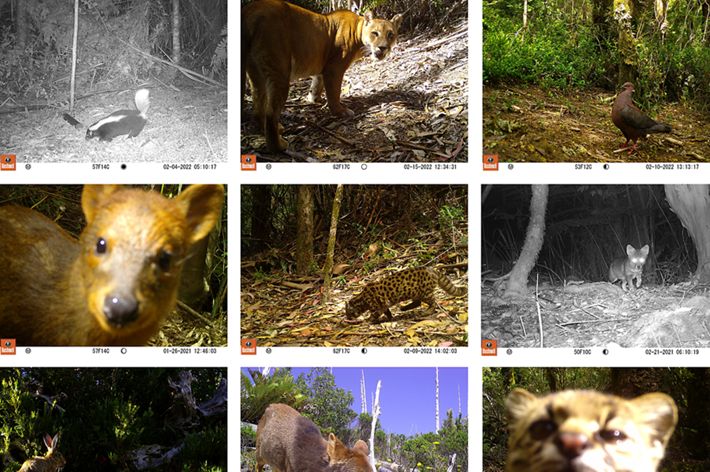

One popular VCR initiative is to give local people the opportunity to train to become park rangers, some of whom recently collaborated with TNC to launch a guide to the forest’s flora and fauna that combines local knowledge with science. To build this knowledge, VCR is also taking part in nature projects, including monitoring amphibians and freshwater ecosystems, and is pioneering the use of wildlife camera traps in Chile.

Local teacher Ricardo Guaitiao has witnessed the positive impact of environmental education and local engagement in the reserve since he arrived 10 years ago. “Before, you could see in children a bad culture of killing everything that moved. For example, on field trips, if they saw a lizard their first instinct was to eliminate it. Children today know the importance of life, and that it’s not harmless to eliminate bees or spiders.” Ricardo sees first-hand how the group activities organized for his students instill a sense of ownership and responsibility for the nature around them, inspiring some of them to take on apprenticeships to become guides or work in forest restoration for the reserve.

Conservation without people is not true conservation. While the logging company excluded Indigenous and other local communities from the area, TNC prioritizes cooperation with local people to protect nature and ensure that communities can reach their fishing grounds and collect non-timber products like fruits and roots in the reserve. The goal is for people to prosper without destroying their natural heritage, including through sustainable cattle grazing and a range of microenterprises. Many of these new small businesses are run by Indigenous women, based on their traditional handicrafts and local food, to bring extra income for their families.

“Before we had to live as spectators, watching all the damage the company did when they applied chemicals to the forest and caused damage in an area where we have sea urchin and piure. It took a long time for the populations to recover.”

- Adelaida Arriaza, President of local cooperative Grupo Ganaderos del Valle

Adelaida Arriaza is the President of Grupo Ganaderos del Valle, a local cooperative that raises cattle in specially designated areas of the reserve, identified through a study with an agronomist at TNC. Her team works closely with VCR rangers to tag and monitor the cattle and make sure they do not harm the native trees. This kind of cooperation is a marked contrast from Adelaida’s previous experience leading the local artisanal fishermen’s syndicate while the logging company still owned the land. She recalls that, “we had to live as spectators, watching all the damage the company did when they applied chemicals to the forest and caused damage in an area where we have sea urchin and piure. It took a long time for the populations to recover.”

“Although it is true that the logging companies provided work,” she continues, “I believe that at the time we did not consider the damage that was done to the forest. Today we have learned to take care of nature, and to live with it, which is the most important thing.”

The funds raised by selling carbon credits have helped to protect the natural wonders of the Valdivian Forest while creating new sources of income and opportunity for local people, including members of the Indigenous Mapuche and Huilliche communities.

Renewed Pride in Natural Heritage

Partnerships and joint activities with communities are strengthening local stewardship and driving a renewed pride in the area’s natural heritage. And there is so much to be proud of.

The Valdivian Forest survived the last ice age to nurture globally significant ecosystems, like the Olivillo coastal forest and the ancient Alerce, the world’s largest and longest-lived tree species. This land of extremes also harbors an incredible wealth of wildlife, including the pudu—Latin America’s smallest deer—as well as one of the world’s largest woodpeckers; the rare southern river otter; and a tiny tree dwelling marsupial, affectionately called the “little monkey of the hill” and considered a “living fossil” by scientists. Conservation efforts also helped discover Darwin’s fox in the area in 2012, and the “comadrejita trompuda” or long-nosed caenolestid was also observed for the first time ever in 2019 thanks to camera trap monitoring.

The funds raised by selling carbon credits have helped to protect these natural wonders while creating new sources of income and opportunity for local people, including members of the Indigenous Mapuche and Huilliche communities, and providing testing grounds for methodologies to help other regions develop their own natural climate solution projects.

But Adelaida Arriaza’s words remind us of what is perhaps the project’s most important achievement: “Today we can breathe clean air into our lungs thanks to the forest we are protecting together with The Nature Conservancy.”

And what could be more important than that?

Quote: Adelaida Arriaza

Today we can breathe clean air into our lungs thanks to the forest we are protecting together with The Nature Conservancy.

Living Carbon:

Stories of Nature's Climate Solutions

In this series, we showcase innovative carbon projects in Africa, northeastern Pennsylvania, Chile's Valdivian Forest, and the Emerald Edge along North America's Pacific coast.