Yes, Climate Change is Raising the Risks—and Stakes—of Extreme Wildfires

A warming climate with dry forests and shifting weather patterns is fueling severe wildfires with unprecedented impacts. There’s still time to act.

Whether it’s through enduring unhealthy air from extreme wildfire events or experiencing those fires directly, hundreds of millions of people around the world are now affected every year by intensifying wildfires. While fire is an essential, natural process that has shaped the world’s landscapes for millions of years, extreme wildfires are becoming more frequent, severe, and extensive.

The evidence connecting the climate crisis and extreme wildfires is clear. Increased global temperatures and reduced moisture lead to drier conditions and extended fire seasons. Prolonged heatwaves can take what was once a natural event in the fire-cycle process and supercharge it into a maelstrom that devastates entire communities. And, crucially, worsening wildfires mean larger amounts of stored carbon are released into the atmosphere, further worsening climate change. Given the mounting impacts associated with extreme wildfires, we need urgent action. There are clear steps we can take but we must take them now.

How wildfires are affected by climate change

Multiple studies show that climate change is creating warmer, drier conditions that cause fire seasons in some regions like western North America to last longer and be more active.

One way scientists know some of the world’s forests are getting drier and more susceptible to burning is by looking at vapor pressure deficit. VPD is like relative humidity but calculated with temperature. It’s the difference between the amount of moisture in the air and the amount of moisture that the air could hold if it was saturated. As an area’s VPD increases, so do the risks of wildfire.

One study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of California at Los Angeles looked at VPD across the western U.S. between 1979 and 2020. Researchers found that most of the increase in VPD is explained by human-caused global warming. According to NOAA, “This study shows that western United States has passed a critical threshold since about 2000, and human-caused climate change is now the dominant contributor to the increase of wildfire risk.”

A 2016 study of western U.S. forests found that “human-caused climate change caused over half of the documented increases in fuel aridity since the 1970s and doubled the cumulative forest fire area since 1984.”

Things will get worse if we don’t slow climate change. Projections show that in some types of forests in the western U.S., an average annual temperature increase of just 1 °C (~2°F) would increase the median burned area per year by as much 600%. In the southeastern U.S., models also predict an increase in areas burned by lightning-ignited wildfires.

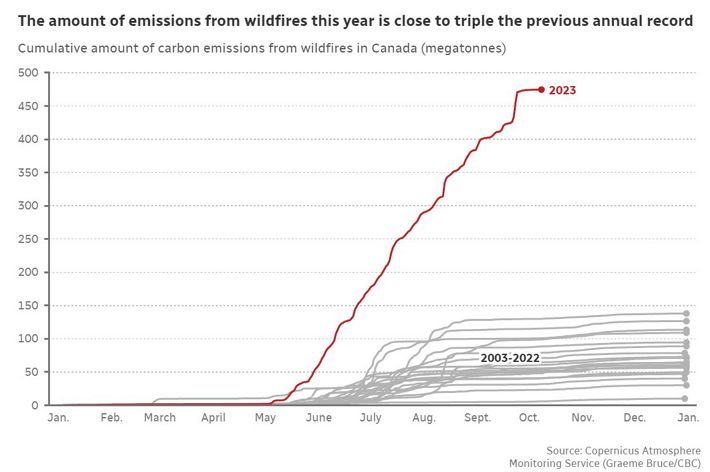

Extreme wildfire smoke is also worse, and affects more than our health

A vivid display of the global impact of extreme wildfires played out in the summer of 2023, when smoke from sprawling wildfires in eastern Canada's boreal forests drifted into New York City, Washington, D.C., and even further. That smoke blotted out skylines and caused record-breaking levels of unhealthy air throughout the northeastern U.S. Canada’s wildfires broke many records and disrupted many lives. In 2023, 7,131 wildfires burned 17.2 million hectares across Canada, more than 6 times the 10-year average, according to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre.

The prevalence of wildfire smoke has also increased substantially since the mid-2000s, and wildfires now account for approximately 25% of Americans’ total exposure to harmful fine particulate matter. Even when extreme wildfire events are thousands of miles away, the fine particulate matter within that fire's smoke can cause a variety of heart and breathing problems, especially for the elderly and other vulnerable people.

Unhealthy air isn't the only impact from the copious amount of smoke and gases from those extreme wildfire events. The carbon dioxide released when forests burn itself accelerates the impacts of climate change.

Quote: Katharine Hayhoe

In a warmer world, we're already seeing more extreme wildfires that put both people and nature at risk.

Reducing the risk of extreme wildfires needs multiple solutions

The origins and behavior of extreme wildfire are complex. Because of this, there’s no one way to address the challenges they pose.

"In a warmer world, we're already seeing more extreme wildfires that put both people and nature at risk," says Katharine Hayhoe, Chief Scientist for The Nature Conservancy. "It's not only climate change: More than a century of fuel build-up, past land and fire management practices, fire exclusion, growing populations moving into and expanding the wildland-urban interface, and a lack of funding to support wildfire resilience all plays a part."

Hayhoe was part of a team that co-authored one of the first predictive analyses of global fire in a changing climate. One of their key findings was that wildfire risks in some areas of the world would increase, while in other areas, it would actually decrease. A rapid decrease in wildfires could actually imperil ecosystems that have long evolved to depend on fire regimes.

Fire can be part of the solution

Part of the answer lies in improving the fractured relationship between people and fire and increasing the amount of proactive, beneficial fire—in the form of such things as prescribed fire and Indigenous cultural burning.

While fire has shaped landscapes throughout the world over millions of years, countries and regions have had different—and evolving—approaches to managing fire and wildfire. In North America, most ecosystems—from ponderosa pine forests in the West to grasslands in the Great Plains and longleaf pine forests in the Southeast—need fire. And Indigenous Peoples have lived alongside and used fire to steward the land since time immemorial, contributing to the evolution of these ecological systems and developing cultures deeply intertwined with fire.

But starting in the early 20th century and extending for well more than 100 years, fire was largely excluded from the places that needed it across North America. This was due to an overemphasis on putting fires out as quickly as possible, an underemphasis on lighting safe, controlled burns, and enforcement of longer-term policies that took fire out of the hands of Indigenous Peoples.

Increasingly exacerbated by climate change, conditions fostered by lack of beneficial fire are making many places more vulnerable to extreme wildfires, with devastating impacts for people and nature.

Today, to help address the challenge of extreme wildfire, we need to bring fire in nature back into better balance and help people prepare for, manage and live safely with fire, TNC is partnering with diverse communities, governments, private landowners, and other organizations. Together, we must:

- Reverse the long legacy of fire exclusion policies and increase the amount of beneficial fire on the ground.

- Grow and diversify the ranks of those who work with fire.

- Support and learn from Indigenous fire practitioners as they revitalize their traditional fire cultures and elevate Indigenous leadership on fire.

- Enhance the safety of communities by helping them better prepare for wildfire and its impacts such as smoke.

We must slow climate change to reduce extreme wildfires

Building wildfire resilience and good management is not enough to meet this emergency.

We also need to confront a key driver of worsening fires: the climate crisis. Thankfully there is important work being done on many fronts and we know the solutions we have to implement. We can solve this problem—as long as we have the collective ambition and tenacity to address it.

- First, we need to rapidly decarbonize our industries. Sixty-seven percent of emissions come from fossil fuels burned for energy. This can be done by responsibly accelerating our transition to renewables and implementing clean energy policies.

- Second, we need to make amends with our greatest ally in this fight—nature itself. We need to help maximize nature's ability to store carbon through a range of natural climate solutions.

- We need to reimagine how we feed our growing population through planet-friendly, regenerative food systems, as agriculture is one of the largest contributors of carbon dioxide.

- And lastly, we need to have very open and frank conversations with one another about the challenges we face in order to inspire the collective effort that’s needed.

We have years, not decades, to tackle these crises. The challenge is daunting but one we must address. Together, we will find a way.